Maybe the lack of copyeditors has become a problem in AMERCIA these days. As the United States gets more and more diverse, and as Spanish continues to climb up the charts in terms of influence and use in the US (where some statistics now say that the US is the second largest Spanish-speaking country in the world), being Latino/Hispanic/Spanish-speaking/bilingual/bicultural is hot right now. English-language coverage of the US Latino world and beyond is the IT thing.

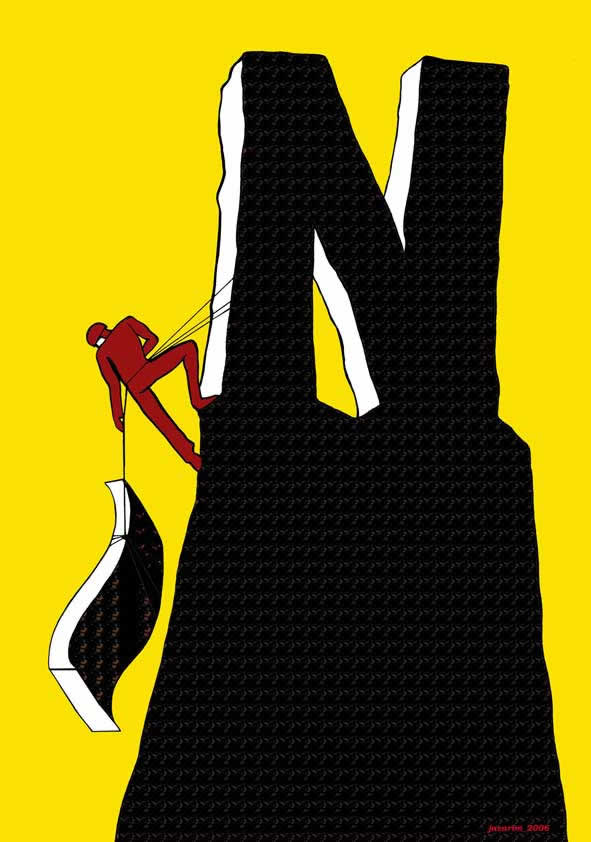

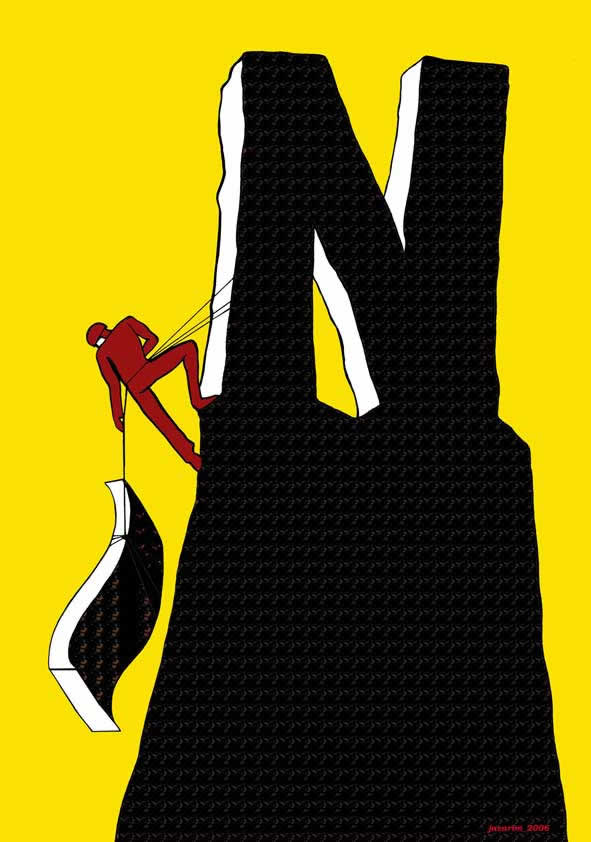

CREDIT: http://unionhispanoamericana.wordpress.com/espana-y-america/nuestra-lengua/o-2/

So, before we get too deep into this and the coverage continues to grow, we would like to everyone know: don’t forget your accents and eñe’s (ñ) Last time we checked, those two very unique and basic parts of the Spanish language still exist and English media sites need to know that just because they don’t know how to actually produce copy with these marks, it doesn’t mean that you should ignore him.

For example, with Mexican elections coming up soon and the recent #YoySoy132 movement taking shape, a lot of stories have been written about Mexican candidate Enrique Peña Nieto, but if you read outlets like the Associated Press, Reuters, the HuffPost (ran the AP story), the Washington Post (also ran the AP story) and the Chicago Tribune (ran the Reuters story), you would see his name as Enrique Pena Nieto. And guess what, people? That is not his name. That is not how he spells it or how he even pronounces it. It’s Pe-nya and not Pe-na, although seeing how Mr. Peña is starting to lose popularity in the latest polls, maybe we should be feeling a little Pena for him. At least, The New York Times adds the eñe.

The same goes for anyone’s name in Spanish. If they have an accent, use it. Most American papers and other English-language outlets from around the world don’t add accents to Spanish names. Last time we checked, those marks are still in Spanish. They are still used and it is a person’s name, like Ramírez, Martínez, Rodríguez, etc. And people, it is and will always be “español.” Screw Google and SEO. (And by the way, around New Year’s, the lack of an ñ in año can lead to tragic consequences.)

And seriously? There is just NO WAY that we will ever say cono when we mean coño.

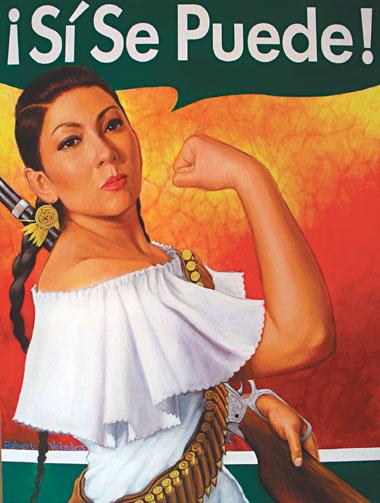

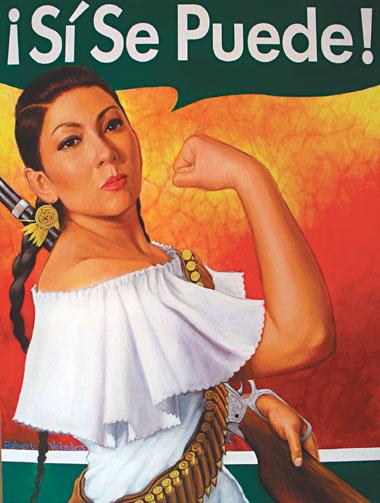

Which leads us to other editorial pet peeves that we keep seeing on several independent US Latino pages as well. Here are the ones that quite frankly are so basic and so simple, you wonder if the page owners actually know Spanish. The biggest culprit? ¡Si se puede! It is not “If it can,” or “If we can,” it is “Yes, we can!” so make sure you add an accent over the i in ¡Sí se puede! And while we are on the subject of actual Spanish conventions, is it that hard to start a Spanish question with a ¿ up front? ¿Pueden hacerlo? Can you do it? Just go to these sites (PC) (Mac) for some help.

No. Sorry, Obama 2012, add the accent. See what La Real Academia has to say.

¡Sí! This is better, even though se and puede should be lowercase.

Why does this even matter to us? Spanish is a language, just like English is. Spanish has it unique characteristics that make it such a unique language. Just like English (we never ever will get silent e, just like we will never get the silent h in Spanish), by not taking the time as editorial producers to actually follow correct mechanics, grammar, and style, you lose the opportunity to A) educate your readers and B) actually appear to care about editorial quality.

And you also make this country’s 35 million native Spanish speakers cringe a bit.

So next time anyone is using Spanish in English copy, just go to El País, which is the Spanish language’s Chicago Manual of Style. Yeah, Spanish has one, too. And we also have real and actual dictionaries too that are the definitive source of the Spanish language. ¿Qué loco, eh?

Thanks to @followthelede for this very funny parody video from Spain when there was this crazy idea that the eñe would get dropped from Spanish altogether to conform with the EU:

See also Scharts, Adam. “Their language, our Spanish: Introducing public discourses of ‘Gringoism’ as racializing linguistic and cultural reappropriation” Spanish in Context 5:2 (2008), 224–245.

Abstract:

This study exposes ‘gringo Spanish’ as a discursive site for the reproduction of privilege, racism and social order in White public spaces. I begin my arguments by exploring Whiteness, doing so by unpacking what I term ‘Gringoism’, which involves the active celebration of a White, monolingual (un)consciousness through particular linguistic and cultural performance. Brief analysis of one particular educational text (Harvey 1990/2003) supports greater discussions of indexicality, intersubjectivity, the elevation of Whiteness and discourses of ‘making sense’ of Spanish-speaking Others. The study closes with implications for the field of Mexican American studies, which in turn offers considerations for scholars studying Spanish within greater educational, anthropological and socio-cultural contexts.

Thank you!