UPDATE, April 1, 2021: Our publisher was finally able to locate the 1974 letter Chávez wrote to the San Francisco Examiner on November 27, 1974. Books about this letter erroneously cited it as being published in November 22, 1974. Here is a thread from our publisher about what the letter said:

Am acknowledging the terms people used in the 70s, while I write this thread. Chávez clearly stated that @UFWupdates opposes the deportation of undocumented workers. Their position was that he was against companies who exploited undocumented works to break up union strikes.

— Julio Ricardo Varela (@julito77) April 1, 2021

The letter adds that Chávez advocated "amnesty" for the undocumented, calling them "our brothers and sisters." This was in 1974.

He spoke to the double exploitation of the undocumented by companies and by a lack of worker rights.

— Julio Ricardo Varela (@julito77) April 1, 2021

The reason I couldn't find this before is that books listed it as November 22, 1974, when it was actually November 27, 1974.

— Julio Ricardo Varela (@julito77) April 1, 2021

I think this letter is definitive proof that conservatives who have tried to paint Chávez as a nativist were just not telling the complete truth, as well as Latino critics. This letter clearly showed a departure.

— Julio Ricardo Varela (@julito77) April 1, 2021

***

ORIGINAL STORY FROM 2013

UPDATE: We did locate a 1972 interview where Chávez explains the tension and context between farmworkers and migrant workers. He mentions that the company brought in “220 wetbacks, these are the illegals” to take over jobs. He places blames on the agricultural companies for denying the workers’s right to organize. Such comments like these were common for Chávez until he was criticized by Mexican Americans groups for his stance, which the rest of this article explains, and how that stance changed.

Ahh, César Chávez GoogleGate, a day we will likely never forget. Much has been written so far, so we will not rehash it here.

We just want to address one “fact” that the mostly conservative crowd is bringing up again, as if it were some breaking news that suddenly discredits the legacy of Chávez (that would be César, and not Hugo). There are now so many definitive “expert” voices saying that César Chávez consistently opposed illegal immigration all his life. That would be partially true if César had left this world in early 1970s, but he didn’t, and by 1974, his views had changed. Even the Daily Caller admits to that. But what do facts matter?

So in the interest putting a closure to this debate and actually trying to educate some people, here is the question that we answer in this post:

Was César Chávez consistently opposing illegal immigration and was he one of the country’s most anti-immigrant voices of his time?

Answer: Yes. And no. Mostly no. He changed his positions and at one point even wrote this in a 1974 open letter in The San Francisco Examiner: “the illegals [are] our brothers and sisters.”(ahh, the 70s, when PC language was not in vogue) History and scholarship would suggest that his positions were to protect the UFW, but in the end, he realized that the political winds were shifting, meaning that people should know their history and what actually happened before jumping to conclusions. Chávez’s views had more to do with how the government and businesses viewed immigration and why the system was broken. In fact, if people actually read the sources, Chávez’s views were not so either/or. What follows is what we found to prove this.

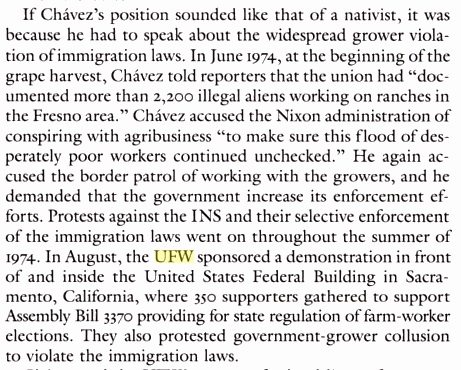

Unlike the one-sided and not fully-researched sources that are being brought up by current outlets, we wanted to share with more scholarly sources about this complexity, so that you can the full picture of it. These first set images come from the book César Chávez: A Triumph of the Spirit:

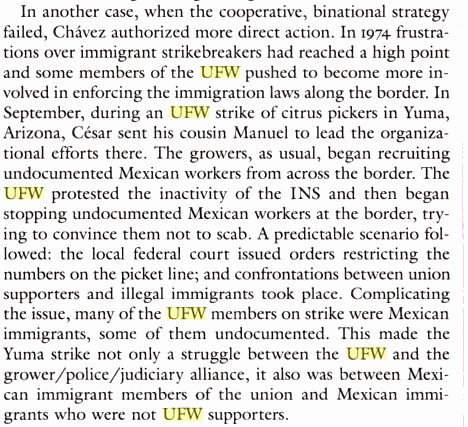

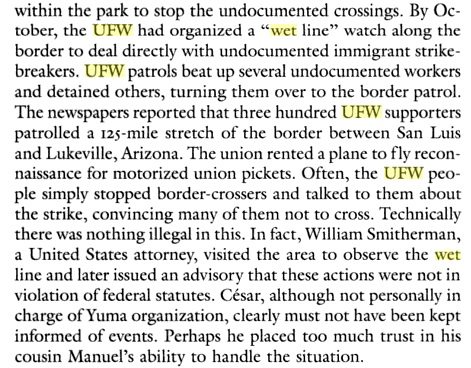

We will get to the 1974 letter in a minute, but also wanted to share what the book says about the “wet lines” that have become the rallying cry from current conservative writers when it comes to Chávez:

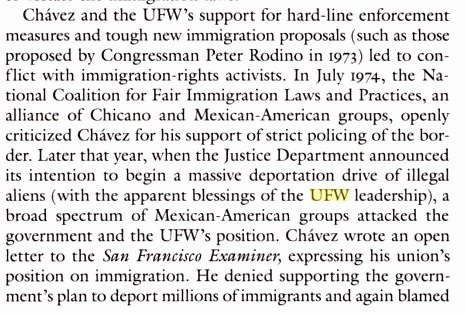

The “wet line” narrative is not as simplistic as what many columnists have presented as fact. (Chávez wasn’t even in Arizona at that time, according to the books and sources we read.) And what about the 1974 open letter to the San Francisco Examiner? What does that have to say about Chávez’s positions? Here is what Randy Shaw’s book says, where Chávez supported amnesty for undocumented workers, the very same workers he was opposing before:

The rest of the story is included in Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants and the Politics of Ethnicity:

[…] latest Chavez apologism comes from an article on Latino Rebels, which draws on excerpts from a few books addressing the union leader’s views on immigration. The […]

Y’all are wrong on Chavez, he was more personally involved in UFW anti-immigrant activities and continued to be anti-immigrant after the letter to the SF Examiner. I’ve described the whole history in detail here: http://openborders.us/2013/04/03/reinventing-cesar-chavez/

Like we said in the piece, Yes and No. Thanks for linking back to us. We never said Chávez didn’t speak out against the immigration system, and like we said in the piece it was also political maneuvering, which all the sources confirm. The 1974 letter where he supports amnesty is a little known-fact that you gloss over in your argument, which you state, and we state ours. Let the readers decide. Peace.

@openbordersblog Like we said in the piece, Yes and No. Thanks for linking back to us. We never said Chávez didn’t speak out against the immigration system, and like we said in the piece it was also political maneuvering, which all the sources confirm. The 1974 letter where he supports amnesty is a little known-fact that you gloss over in your argument, which you state, and we state ours. Let the readers decide. Peace.

@latinorebels I agree that the readers should decide. But let them take all of the evidence into account – Chavez’s campaign to report undocumented workers to ICE, his demands that Congress increase INS enforcement, his personal communications that show antipathy towards all undocumented immigrants, and his lack of enthusiasm on promoting immigration reform.

If you had included Frank Bardacke’s definitive UFW history, “Trampling Out the Vintage” and also looked at the media coverage of UFW in the 1980s you would have presented a more critical but more complete analysis of Chavez.

@openbordersblog Like we said in the piece, it was political necessity. The fact that you claim we are apologists is a bit off and inaccurate. The issue is a complex one, and we are aware of Berdacke’s book, and one its biggest faults is his lack of knowledge regarding the UFW within the bigger context of overall Mexican American movement at the time. Other people who also were with Chávez at the time tell different accounts. Such is history and how it is shared. Once we have more to share, we will. Thanks again for the comments.

@openbordersblog Like we said in the piece, it was political necessity. The fact that you claim we are apologists is a bit off and inaccurate. The issue is a complex one, and we are aware of Berdacke’s book, and one its biggest faults is his lack of knowledge regarding the UFW within the bigger context of overall Mexican American movement at the time. Other people who also were with Chávez at the time tell different accounts. Such is history and how it is shared. Once we have more to share, we will. Thanks again for the comments.

@openbordersblog Our intent was to address specific points about the wet lines and Chávez’s actions in the early 70s and how his position evolved. That was all.

@openbordersblog Our intent was to address specific points about the wet lines and Chávez’s actions in the early 70s and how his position evolved. That was all.

@openbordersblog And Chávez was anti-strikebreaking and against the companies that hired unauthorized workers to break those strikes. That is different from saying that you think we said that Chávez was for comprehensive reform, but from what we have read and studied, he understood that the system was broken and it was benefitting union or those unauthorized. We are just responding to the critics who boldly proclaim that Chávez did not support amnesty, etc. Within the political necessity, he did. Thanks again. We will share more, especially the 1974 letter he wrote.

@openbordersblog And Chávez was anti-strikebreaking and against the companies that hired unauthorized workers to break those strikes. That is different from saying that you think we said that Chávez was for comprehensive reform, but from what we have read and studied, he understood that the system was broken and it was benefitting union or those unauthorized. We are just responding to the critics who boldly proclaim that Chávez did not support amnesty, etc. Within the political necessity, he did. Thanks again. We will share more, especially the 1974 letter he wrote.

@latinorebels I couldn’t find the letter in my searching so I’d be interested to see it, but it might be difficult to get. I may head to the Library of Congress soon and look for it there… I’ll send it your way if I find it.

@openbordersblog We will do the same. We should have it by this weekend. Thanks again!

@openbordersblog We will do the same. We should have it by this weekend. Thanks again!

@openbordersblog By the way, we read your critique of our “reinvention” and we just way to say that you are a bit off in your interpretation. Our response:

He only opposed scabs who were undocumented and [César Chávez] wasn’t responsible for the UFW’s Minutemen-like patrolling of the Arizona-Mexico border: Chávez was not there in Yuma, but you must have not read the excerpt we refer to. Some undocumented workers struck with the UFW and some did not. So for those who did join the UFW, why did they join? If you claim that the UFW was 100% anti-immigrant. that Yuma passage and its details would counter that.

“He ultimately came to support immigrant rights in 1974 when he outlined his views in a letter to the San Francisco Examiner:” Again we put it in the context of the political necessity. Did you not read the detailed piece? Even the author of the piece admits that Chávez had to be delicate about it.

The crux of all this is simple and it is also one of the conclusions made here: comparing Chávez’s views on immigration and equating to current hard-line restrictive immigration hawks is like comparing apples to oranges. This all stemmed from the “outrage” that Chávez was featured on a Doodle for Google on Easter Sunday. People were quick to “prove” that Chávez was a Latino nativist. We dispute that. That is too much, but to say that we are “reinventing” him is also inaccurate. but hey, if we are your straw man, then we take that as a compliment. We understand that you need to feed the narrative to those who don’t agree with us.

@openbordersblog By the way, we read your critique of our “reinvention” and we just way to say that you are a bit off in your interpretation. Our response:

He only opposed scabs who were undocumented and [César Chávez] wasn’t responsible for the UFW’s Minutemen-like patrolling of the Arizona-Mexico border: Chávez was not there in Yuma, but you must have not read the excerpt we refer to. Some undocumented workers struck with the UFW and some did not. So for those who did join the UFW, why did they join? If you claim that the UFW was 100% anti-immigrant. that Yuma passage and its details would counter that.

“He ultimately came to support immigrant rights in 1974 when he outlined his views in a letter to the San Francisco Examiner:” Again we put it in the context of the political necessity. Did you not read the detailed piece? Even the author of the piece admits that Chávez had to be delicate about it.

The crux of all this is simple and it is also one of the conclusions made here: comparing Chávez’s views on immigration and equating to current hard-line restrictive immigration hawks is like comparing apples to oranges. This all stemmed from the “outrage” that Chávez was featured on a Doodle for Google on Easter Sunday. People were quick to “prove” that Chávez was a Latino nativist. We dispute that. That is too much, but to say that we are “reinventing” him is also inaccurate. but hey, if we are your straw man, then we take that as a compliment. We understand that you need to feed the narrative to those who don’t agree with us.

@openbordersblog One more thing: the publication of the 1974 letter would make sense given that after the failure of the Campaign for Illegals, Chávez was losing support within the Chicano movement. Hence the political necessity we suggest.

@openbordersblog One more thing: the publication of the 1974 letter would make sense given that after the failure of the Campaign for Illegals, Chávez was losing support within the Chicano movement. Hence the political necessity we suggest.

@latinorebels Yes, we’re in agreement on that point. The “reinvention” was a reference to the immigration rallies on Chavez Day. While I do get your purpose in countering the particular narrative that Chavez was against amnesty, I called you guys apologists for downplaying the degree to which he was personally involved in pushing the UFW towards anti-immigrant politics, even as late as 1979. And this is the internet after all, so one can’t help but throw shrill labels like “apologist” around.

@openbordersblog No worries, thanks again for the conversation. It is always cool to connect with those who link to our pieces. We should have more up in the next few days and we plan to address the 1979 and later years as well, and when we get the letter, it should help shed some light as well. Have a great night!

@openbordersblog No worries, thanks again for the conversation. It is always cool to connect with those who link to our pieces. We should have more up in the next few days and we plan to address the 1979 and later years as well, and when we get the letter, it should help shed some light as well. Have a great night!

@openbordersblog FYI, have our editors in Bay Area locating the 1974 letter. Should have it by Monday/Tuesday.

@openbordersblog FYI, have our editors in Bay Area locating the 1974 letter. Should have it by Monday/Tuesday.

[…] latest Chavez apologism comes from an article on Latino Rebels, which draws on excerpts from a few books addressing the union leader’s views on immigration. The […]

Mexicans have a lot more reason to thank American farmers than Chavez, who never improved their lives economically in any way whatsoever.

Mexicans have a lot more reason to thank American farmers than Chavez, who never improved their lives economically in any way whatsoever.

While professing to be ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html profoundly disturbed’ by the aggression of anti-Semitic Germany, Roosevelt continued his special http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html friendship for Soviet Russia http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html after its attacks upon Outer Mongolia, Poland, Latvia, Esthonia, Lithuania and Finland. Professing an adoration for ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html democracy’ he refused, as the Jews control 90 percent of the scrap iron business, to invoke the Neutrality Act against http://cintaberita.com Japan in its http://raksasapoker.com/war on China, or against Russia when, with Germany, she invaded Poland and attacked Finland. He extended a warm welcome to the Communist Ambassador Oumansky when he presented his credentials and, on the same day, displayed marked coldness toward the newly appointed Ambassador from Christian Spain

Growing up in the Central Valley as formerly undoc person, Indigenous background, and working the fields with my parents.. you were brought up to have a fairy tale of Cesar Chavez and the UFW. It’s not till you get older and really read into the history that you discover a very Mexican- American-Chicanx-Latinx nationalist approach to what the UFW organizing. I wish in K-12 they did a more truthful and critical analysis of this movement so children at an early age know the complete history and not a washy one.

[…] year around March 31, also known as César Chávez Day, the predictable, standard pattern of conservative takes (and takes from some Latinos) that Chávez was always a 100% anti-immigrant […]