Latino Rebels is running a series of pieces by local Bakersfield journalist/writer Nicholas Belardes about the in-custody death of David Sal Silva. This is the series’ second post. You can read the first post, “Part One: Culture of Drugs” here.

Part Two: Culture of Violence

BAKERSFIELD, CA – There is a solemnness to the surveillance video. A buzz-hum enters the brain. A taut feeling in the abdomen. I watch at the dining room table from the edge of my seat. My laptop has become a window to black-and-white ghost movements. A man dies. I know this. His name is David Sal Silva. He is 33 years old. There is violence in the video. I know this too. But there is no blood and gore that I can see. The camera is too far away. It’s too grainy. Too dark. Only ethereal swings of nightsticks, some of them two-handed, as if ghostly boys pushing and shoving each other out of the way, are gathering around a T-ball set, smacking a ball over and over, all hoping for a homerun.

Silva is in the dark wearing a blue shirt and tan cargo shorts, white socks and black shoes. He’s already been escorted away from the Mary K. Shell Center and is lying on the corner of Palm and Flower streets. A security guard watches him from the hospital parking lot—the same guard who escorted him away from the substance abuse center where he sought help.

Soon, a sheriff’s deputy knuckle rubs Silva on the chest to wake the large man. The violence begins. This is the initial point of confusion for the rest of us. Silva is brought to his feet by a deputy, after Silva falls on his face, only to immediately have the same deputy decide to break him back down to the ground.

This is the fine line between peace officers and military tactics. This is our culture of violence.

In American culture, legalities justify that the officer can begin to tactically use violence to make Silva submit. This appears to be the Kern County Sheriff’s Office point of view, regardless of who struck who first. An officer wanted Silva back on the ground. Use of force was then necessary and justified, according to authorities.

Silva did not get on the ground.

Kern County Sheriff Donny Youngblood, in a press conference, along with a Kern County Coroner Report on Silva’s death has provided viewpoints of sheriff’s deputies, a paramedic, a security guard and the coroner. Missing are Silva’s bewildered thoughts, his point of view, the thoughts of a man not only under the influence, but in a world of desperation and helplessness.

One possible explanation missing from any report on Silva’s point of view are the words excited delirium, a controversial condition affecting drug-using, obese men. Not unanimously recognized by medical associations, the condition, according to Laura Sullivan in her 2007 report, “Death By Excited Delirium: Diagnosis Or Coverup,” burst on the scene in the 1980s when cocaine entered American mainstream usage.

In 2003, a patrol car zoomed into the lot of a White Castle in Cincinnati, Ohio. A 350-pound man was seen stumbling around, yelling. He is Nathaniel Jones, 41, father of two, who was working in a group home. Lisa Sullivan’s NPR report claims Jones argued with two officers before a beating commenced that took his life. The incident was caught on video.

He seems confused; he can’t keep his balance. The officers close in. The officers order Jones to get down but they can’t seem to catch him. He throws his body at one of the officers. Out come the nightsticks.

They strike him about 40 times. Jones is on the ground when more officers arrive with nightsticks. Jones calls out for his mother. That’s the last thing he says.

Jones stops moving. He dies a few minutes later.

The coroner found that Jones did not die from excessive police force but from a number of causes — such as heart failure, obesity, drug use and asphyxiation. He later told reporters that Jones’ death could have been the result of something called excited delirium.

Did Silva tire himself to the point of death like authorities suggest happened to Jones? Are brutal submission tactics being overused on society?

Sullivan quotes Dr. Vincent Di Maio in her article: “What these people are dying of is an overdose of adrenaline . . . They [law officials] bind the feet, and every one stands back and they’re panting. And then finally someone says, ‘He’s not breathing.'”

Why wasn’t an ambulance called to take Silva back to the hospital? Being strapped to a gurney instead of being forced into submission by an attack dog and nightsticks is an obvious solution.

Yet America’s culture of violence in law enforcement utilizes other tactics. As recently as 2005, in the Kern County beating death of inmate James Moore, we can see another example. The incident was written about by Shannon Carter Choate in a recently written memoir titled, “Snitch.” Choate was witness to the event and her testimony was used to convict fellow officers. She is a student of The Invisible Memoirs Project. Her full story might be published later this year.

We all joke that the Central Receiving Facility (CRF) is a hotel for inmates. Stinks more than anything. Rancid feet, sweaty body odor, urine-soaked clothing, stale alcohol seeping through pores—the usual assortment of flavors. Foot funk is strongest in Receiving where fresh arrests off Kern County streets marinate in holding cells, waiting to be booked and housed.

Choate describes an unruly inmate named James Moore who officers suspect is on PCP, but is later found to have been enraged for unexplainable reasons. Several officers attempt to control Moore when Choate suggests calling in medical services.

“Do you want to call an ambulance?” I ask.

“No,” Holmes says. “We can handle it.”

Calling an ambulance would minimize the use of force from any officers, no matter how much the inmate fights. But what do I know? I’m a female subordinate. I keep my mouth shut . . .

As Moore is beaten, including his head smashed by a knee, Choate again suggests an ambulance.

. . . Sergeant Holmes and I stand to the left of Moore when I notice blood pooling up inside his ear canal. Blood streaks down his cheek and jawline.

“Usually, blood coming from the ear is not a good thing, Sarge,” I say to Holmes.

“Neither is blood coming from the eye,” he says. “He’s got blood coming from his right eye, too. I think it’s just a scratch.”

I can’t see, but figure the eye injury is minor given Holmes’ lack of urgency. The blood in the ear is alarming. I feel the need to question my sergeant’s call. “Are you sure you don’t want to dispatch an ambulance?” I can’t shake a sense of doom.

Again Choate’s request is declined. Finally another officer offers the same suggestion to help subdue the inmate.

“Has anybody thought of calling an ambulance?” Dick asks.

“I’ve suggested it twice, but Holmes says no. Don’t we look ridiculous?”

“If we call an ambulance, they strap him to the gurney, the fight is over,” I say.

“That’s the best idea I’ve heard all night,” Lambosi says.

Holmes concedes. “Ok, make the call.”

Hall Ambulance is on the way. Relieved, I call Dick. “Now we can stop looking like Keystone Cops.” As I snicker, shouting erupts.

The Kern County Coroner’s report lists substance abuse under the category HOW INJURY OCCURRED for how David Silva died.

Under CAUSE A the report lists Hypertensive Heart Disease as well as Acute Intoxication, Chronic Alcoholism, Severe Abdominal Obesity, Chronic Hypertension and Acute Pulmonary Cardiovascular Strain.

Excited delirium?

I was talking to a Latino man who was once in the Bakersfield Police Department reserves in the late 1970s. I will keep his name anonymous as our conversation was simply the result of a brief walk across the street to talk to neighbors waving from their porch. We got to talking about David Sal Silva, and why officers didn’t just weigh down the man with their own body weight.

“Why didn’t the officers just outweigh him? That’s what we were taught in the reserves,” he said. “Anyone can beat a guy to death.”

His words stuck with me. For some reason I thought of the sport of wrestling, how it has transformed from athletes just learning grappling techniques to athletes now cross-training to learn ultimate fighting so lucrative careers can develop post-college (or at least side jobs as bouncers). From boys learning how to pin other boys to the ground, to boys learning how to strike crippling blow after blow.

Our culture of violence has transformed, is transforming.

Playing politics, Sheriff Youngblood has gotten upset at the media citing an emotional response to Silva’s death. Let’s remember, he’s a politician. An elected official. Does he really think all emotion can be taken out of death at the hands of law enforcement in our culture of violence? Who is he playing politics with? Who might he be protecting?

“The sheriff’s department has stonewalled this entire event,” attorney David Cohn says in a press event days after Silva’s death. He also uses the words “Brotherhood of the Blue Line,” as if the title of a true crime novel about law officials reluctance to tattle on other law enforcement officials. Like Shannon Carter Choate’s “Snitch,” you just don’t cross the law in Kern County.

“Silva wasn’t beaten to death. He wore himself out,” Choate said, this time taking the side of law enforcement officials. She doesn’t even like the word beating. She used the word strike, citing the deputies’ legal justification to do so.

Like any curious writer I looked up beating in the dictionary, which led me to the word, beat. Beat means “to strike violently or forcefully and repeatedly.” Strike means “to deal a blow or stroke.” Blow means to hit or strike, and hit means both stroke and blow, which, all really means is when you put them together, or use them interchangeably, they all mean “to beat.”

Either way, perhaps both Choate and I are both right for the time being: legal, but brutal and unfair. And while video evidence could still prove the sheriff right or wrong, such tactics were likely never necessary in the first place.

Which brings me back to that grainy surveillance video and our culture of violence in Kern County, and America for that matter, and how the mentally ill, including drug users, and those who may fall under the auspices of excited delirium, are often brutalized instead of rescued.

*Sidenote: At the last minute I decided not to interview the Silva family. While their voices would have lent further credibility to this article, I felt their pain would have been unreasonably increased because of writing this piece on the culture of violence.

***

Fantastic writing.

DignityPeace We agree 100%.

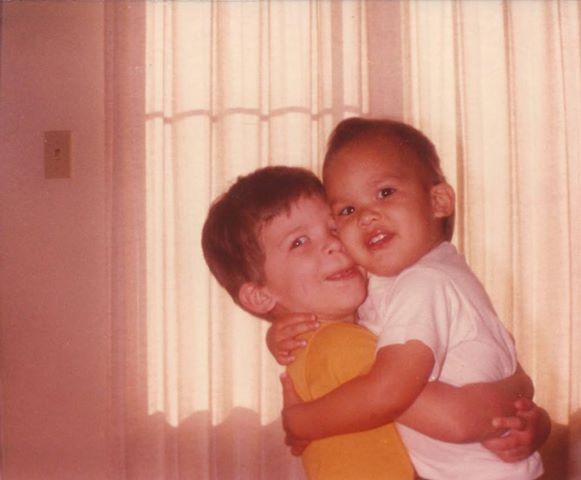

MY BOYS AS SHOWN IN THIS PICTURE LOVED EACH OTHER SO MUCH AND THEY WILL MAKE SURE THAT JUSTICE IS DONE.

MERRI JEAN SILVA

flowers33 Blessings to you, Mrs. Silva. Our prayers and love are with you and your family.

We are not denying http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan and we are not afraid http://yakuza4d.com confess, this war http://yakuza4d.com/home is our war and that it is waged for the liberation of Jewry…Stronger than all fronts “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar together is our front, that of Jewry. We are not only giving http://cintaberita.com this war our financial support on which the entire http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main war production is based. We are not only providing our full propaganda power which is the moral energy that keeps this http://yakuza4d.com/hasil war going. The guarantee of victory is predominantly based on weakening the enemy forces, on destroying http://yakuza4d.com/hasil them in their own country, within the resistance. And we are the Trojan Horses in the enemy’s fortress. http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi Thousands of http://www.cintaberita.com Jews living in Europe constitute the principal factor in the <a href=”http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi”>Agen Togel Online</a> destruction of our enemy. There, our front is a fact

An exact representation of the universe, of its evolution, of the development of mankind and of the reflection of this evolution in the minds of men, can only be obtained by methods of dialectics.The goal of<a href=”http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html” title=’agen bandarq’>Agen bandarq</a><br />Russia is in the<a href=”http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html” title=’domino online’>Domino Online</a><br />first instance a<a href=”http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html”title=’agen bandarq’>agen Bandarq </a><br />World-Revolution.<a href=”http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html” title=’bandar domino99>Bandar domino99 </a>The nucleus<a href=”http://dokterpoker.org/Register.aspx?lang=id” title=agen domino online’>agen domino online </a>of opposition<a href=”http://dokterpoker.com/Register.aspx?lang=id” title=’agen domino online’>agen domino online </a>to such plans is to be found in the capitalist powers, England and France in the first instance, with America close behind them. <a href=”http://dokterpoker.org/” tilte=’agen bandarq>Agen Bandarq</a><br />

[…] “Part Two: Culture of Violence” […]