What do Sonia Sotomayor, Jennifer López, Anthony Romero, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Mario Vázquez and Jon Oliva have in common? These Latinos called Bronx their home. So did Tito Puente, Prince Royce, Willie Colón and many others. I’ll throw in a couple of honorary Latinos such as Edgar Allan Poe, Marian Zazeela, Woody Allen, Neil Simon and Mark Twain to remind everyone there’s much more to the Bronx than Hip-Hop and overly exaggerated gesticulations, mainly produced by shenanigans showing their cheap underwear with copious amounts of unnecessary pride. And proud we Latinos should be of our next Bronx hero.

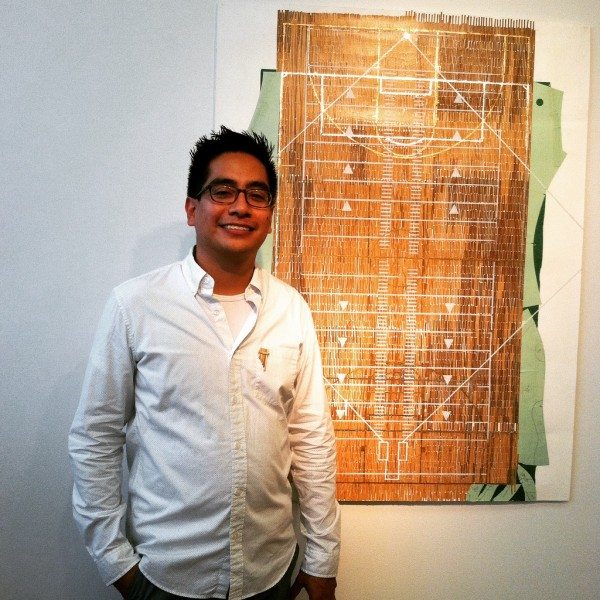

Hailing from the soon-to-be-gentrified, poorest congressional district in the contiguous United States, and headquarters of the unionized-corporate-sports-sanctuary better known as the Yankees Stadium, comes our next Latino Rebelde: Ronny Quevedo. This magnificent visual artist earned his MFA from the Yale School of Art and BFA from The Cooper Union. He has participated in residencies at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Project Row Houses, the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, the Lower East Side Printshop, The Bronx Museum of the Arts and Aljira Contemporary Art Center. Impressive, right? So, when I heard about his latest exhibit, Home Field Advantage, I literally canceled my dinner date and ran to his opening reception in hopes to meet him, share a bottle of wine and have a chat.

MF: This is your triumphant return to the Bronx. My condolences for being in Houston for so long…

RQ: [Loud laughter] Well, I was there for an artist residency called The Core Program. Before that I was doing my MFA at Yale University. I was away for a while.

MF: You did an MFA at Yale. WOW! How many Latinos were enrolled in an Arts MFA at Yale?

RQ: At the time there were probably 6, 7 of us in the whole arts program.

MF: 6 or 7 out of how many?

RQ: Around 60.

MF: So, it’s not a very diverse MFA program?

RQ: It felt like we had a good stake in the conversation, nevertheless. It’s a small group of people that come in and out. So, our conversation was entertained.

MF: Was that “conversation” factored into the art you’ve created during and after your MFA?

RQ: Yes and no, I think the idea of migration and what kind of symbolism came from that, totally changed after grad school. I was doing a lot of printmaking and after grad school I decided to go back to my first love, which is drawing and working with paper. And that’s what I’m working on right now.

MF: How influential is our Latino culture in your work?

RQ: A lot of Latino references, but mostly have to do with the history of Latin culture. I’ve been doing a lot of reading on pre-Colombian text. Joaquín Torres García, from Uruguay, for example, is someone who studied the primitive and pre-Colombian cultures of Latin America and then started making abstract paintings. He has a huge influence on me. I had the opportunity to talk about him during grad school. There’s also the influence of my upbringing in the Bronx; listening to salsa, hip-hop, merengue, cumbia at the same time, while I’m trying to find out where I’m from. My parents came over when I was very young and I basically grew up in Bronx, NY.

MF: What strikes me as incredibly fascinating is that you’re basically doing an examination of pre-Latinos and post-Latinos. What are the differences?

RQ: The truth is we aren’t that different. There’s a lot of diversity, yes. Now, let’s try and point them out. We can’t. That’s why I’m interested in the history of all these references. So, that’s why I went back to meso American ball games, Inca culture and tunics and how architecture relates to that. There’s so much infused histories that we’re unaware of, except for the symbolism. I went to Ecuador recently and I went to the archeology museum in Ecuador. The curator was telling me about the Mexican- Ecuadorian trade before the conquistadors. All of that history plays out in all of our countries. There weren’t many references because it wasn’t in written language and if it was, it was burned to the ground. So, growing up in the Bronx is realizing that our diversity is an inheritance.

MF: Your work is very political too. How much of that comes from a place of “honoring ancestry” and how much of that comes form a place of “anger”?

RQ: Honoring ancestors and this inheritance is a way to advocate for this resiliency and the anger that may still exist. It’s a coping mechanism.

MF: Wait, so the creation of art is a coping mechanism?

RQ: Yes, that’s why some works are in abstract forms. You create with the energy you want to relate to people. That’s not to say I’m complacent or I’m trying to dismiss some things that are going on. Sometimes you can’t translate things verbatim.

MF: Is that why some of your work is “open ended” or “in progress?”

RQ: It’s only open ended in the sense that abstraction can’t be literal. You can’t give map to what abstraction does.

MF: And this is coming from someone that is interpreting maps…

RQ: Yes, but that’s the idea behind it. How can I take this information and try to make sense of it? Being unstable doesn’t have to have a negative connotation.

MF: Being unstable shouldn’t automatically carry a negative label?

RQ: The idea of instability doesn’t have to be negative. I grew up with instability. I didn’t have all the resources.

MF: There’s a school of thought that really believes that instability in some artists —be it a drug addict or someone who suffers from depression— actually serves a purpose. Do we really need to recognize instability as a big contributor to the arts and politics universe?

RQ: In a way you’re talking about duality. You can’t have hope or progress without suffering. You need the other side of things to position yourself to see where you are. And it’s not to say that suffering can’t be coped with or you need to become a victim in order to talk about suffering. The learning curve is to delineate the differences and then learning to create and cope. I personally study the legacy of Mayan culture, the legacy of my father, the legacy of migrants to the US to delineate those things.

MF: You talk about the legacy of your father and it triggers this question: when was the moment you said: “I’m going to be a political visual artist”?

RQ: I know this sound cliché, but my brother once said: “Man, you’re always making stuff.” We didn’t have the money to buy a toy gun, so I made one out of cardboard. We didn’t have money to buy a guitar so I cut one out of a cereal box and clip rubber bands. I couldn’t go outside to play games, so I did a marble game board with a shoebox. I was always trying to find ways to compensate for the lack of a resource.

MF: Is that how art is born? Inventing something from nothing?

RQ: I think the idea of transformation is really important.

There’s something about art making that it’s only expressed through that form. For me it has always been about the idea of wanting to have something, but not having it. Why is that disconnect?

MF: And that, in a sense, is very political. I can see how, as a child, you’re already making those socioeconomic connections.

RQ: Yes, growing up you’re not educated enough to realize the difference. So, the idea of a good painting its drawing religious symbols or the idea of a good photograph is doing it in black and white. Then you realize these pieces of art don’t look anything like me or do not speak to me. The Mona Lisa doesn’t look like my mother. You start realizing the disconnect between the materials that you have available and these high art pieces, not only in museums, but also in church or high-end fashion.

MF: Interesting, on my end I can say very few people may go to an opera to be entertained. The idea of the elite, high-end art seems to be that disconnect. Do you think museums have become more accessible and more open to different points of views?

RQ: Visual culture is prevalent. People are now more visually literate than anything. Advertising, branding, fashion are arenas masses understand even before they can deconstruct the book. As a visual artist you realize that the culture is an incredibly bountiful place to be. That’s liberating. However, there’s kind of limited landscape of that visual culture. We open our eyes and say: “Wait! I don’t see brown or black people in these paintings.” Even artists, I don’t see many last names that resemble the people I grew up with. Once you understand this, you realize there’s almost no diversity in the museums right now. I think a lot of Latino artists and artists of color in general; realizing that for example the slave trade had many influences it affects architecture, and cultural identity.

MF: Now, let’s get personal because this is fascinating. Have you experienced discrimination in the art world?

RQ: Yes, I experienced seldom times especially in my undergrad. We did a trip to the library and looked up the History of Latin American art and its one textbook. Then the professor tells me: “yeah, but those are mediocre artists. They’re second-rate painters.” I asked myself: “are they second-rate because they fit in this one book, or because Latin American or they simply are second rate.

MF: Let me be devil’s advocate. You already established your art is based in self-sustainment. We can sit here and claim the people in power, mainly white male dominant, continue to belittle us and even destroy us. However, aren’t we our own worst enemies if we expect the hand-delivery of our own work? Shouldn’t we do the research, write the books and “keep them in the family?”

RQ: Definitely, it’s crucial we feel autonomy as artists and we should claim our space. It’s important making spaces for us. Deliver art to our own. If we don’t take this into our own hands we continue the circle of victimization. This includes financial development and resource availability. We need to also recommend others in line with our work. In other words, we need to develop sustainability.

MF: Should street art or graffiti be in a museum?

RQ: If your work comes out of facing the dynamic of a power structure and changing that structure, like graffiti does, that in itself it’s in competition with the power dynamic. It’s resistance and rebellion. Everything get’s co-opted. I’m not an expert on street art or graffiti, but I always ask myself: “why can’t the idea of a museum be transformed?” There should be space for that.

MF: What is your unique voice? How would you describe it?

RQ: The idea of assemblage comes from debris. Where does debris come from? An area of riots, violence, protests. I’m taking that information, synthesizing it and turning it into a drawing or a sculpture.

MF: What would you like our community to take away from your work and that unique voice?

RQ: I feel like all of it’s malleable. You can alter everything and make it your own.

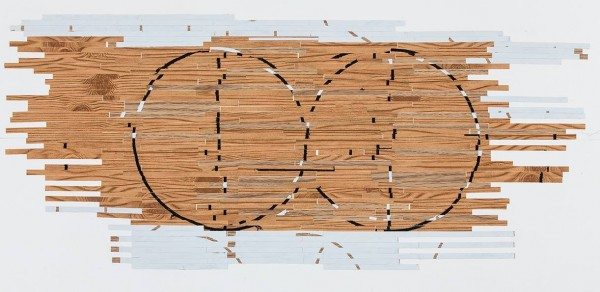

MF: Home Field Advantage is a collection of art depicting stadiums, sports arenas and gymnasiums. It represents the boundaries and rules of engagement within sports. However, the interpretation is to reflect sociopolitical and socioeconomical limits. What made you go: “wow this basketball court looks like our life”?

RQ: Again, when I was always creating games. I always thought: “Fuck, if I can’t find it, I can do it.” Once, in seventh grade teachers told us we couldn’t play cards anymore. I went home and decided, if I can’t play cards anymore, I’ll create a game. I built this new game. I made the characters based on video games. Then I gave dice to the players. It had rules and everything.

MF: You did this when you were 11 years old? That’s hysterical!

RQ: And I’m proud of it. It got so popular I had to do a second one.

MF: I’m just fascinated. You took sports and turned them into art. You took a soccer ball and turned it into a globe. It sounds to me this not just you being fucking pissed off at the status quo, but it comes also from rebellion. What is your definition of a Latino Rebel?

RQ: It comes from resiliency. There are structures in place that want to erase us or want us not to know our history. A Latino Rebel is someone who is constantly defying what’s in front of them, through study, and rigorous investigation despite of the possibility it could easily be erased; burned to the ground. You do it anyway and if it’s erased, at least you did it.

MF: Ronny, I have to say, you’re truly a role model at an inspiration. Congratulations and please, I want to buy Cabeza Mágica!

Learn more about Ronny Quevedo.

***

Marlena Fitzpatrick is the CEO of Editorial Trance and the Music and Arts Contributor for Latino Rebels.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.