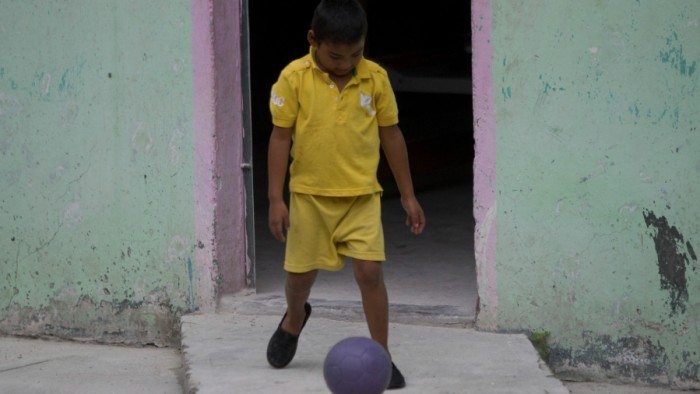

A boy in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, the murder capital of the world (Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos/Flickr)

The New York Times published a long piece yesterday in which short-story writer Luke Mogelson details the real-life drama of four Hondurans trying to flee the dangers of their homeland and make it into the shadows of the United States. In an early scene, Kelvin Villanueva, the father of four U.S. children (two biologically), is interrogated by an asylum officer looking to determine whether Kelvin risks imminent danger in returning to his home town of San Pedro Sula:

Villanueva later described the torture and murder of the uncle who directed the youth group at his family’s church. In 2013, the uncle disappeared after complaining to the police about the 18th Street Gang harassing the group members. A few days later, his body turned up in the Chamelecón River covered with puncture wounds, which investigators deemed to have been inflicted by an ice pick.

‘How do you know the gang is connected to the police?’ the asylum officer asked.

‘Everybody knows that in my country,’ Villanueva said.

‘Your attorney submitted an article that indicates the police captured a leader of the 18th Street Gang,’ the officer pointed out. ‘If the gangs are working with the police, why would the police arrest their leaders?’

‘They arrest people so the community thinks they’re doing something. But then they’re out of jail in a week or two.’

‘Why are they released after a week or two?’

‘This is the question that all of the good people of Honduras ask.’

‘Is there anything else that you’re afraid of in Honduras?’

‘No. Just losing my life.’

Although the officer found Villanueva credible, she did not consider him eligible for asylum; the immigration judge agreed. Villanueva was sent to Louisiana, where he was loaded onto a plane with more than a hundred other Hondurans.

Since a flood of women and children from Central America began turning up on the Texas-Mexico border in the summer of 2014, the U.S. government refused to label them refugees, opting instead to refer to them as “migrants,” a word which implies they’re little more than tourists. Birds migrate every spring and autumn. Workers migrate, going wherever they can earn a dollar. Refugees, on the other hand, don’t migrate. They scramble for their lives.

Few United Statesians believe that the Central Americans scrambling across Mexico and desperately pounding on their door are in any real danger back home. In their minds, under those tattered, dusty clothes lies a lazy loafer or a scheming evildoer. Many Latinos and non-Latinos — including my own Honduran grandmother, whom I love nonetheless — have convinced themselves that recent reports of routine bloodshed across the isthmus are just the exaggerations of a liberal media working to present every poor person as a victim and every government as an oppressor. Ironically it’s the sheer number of reports and personal accounts detailing the manic outbreak of violence which fuels the skepticism of the doubters. The number of teenaged girls raped on La Bestia cannot be that high, they insist. Whenever I cite the number of people killed in her home town of Tegucigalpa, my grandmother rolls her eyes and sighs, as if to say “you poor, gullible little boy.” If I keep plying her with figures and stories, she boils into a rage — at me.

As with most situations viewed from afar, the hellish everyday realities in Honduras are much worse than they appear to anyone who isn’t there and hasn’t been there. The people of Honduras have acquired an intimate knowledge of the violence all around them, growing numb to it out of necessity. For every story that shocks the average NPR listener, many more atrocities are unreported. Death has become mundane, and thus hardly worth mentioning. The corpses, like those lying facedown in the intersection in Mogelson’s piece, are passed by like familiar scenery. Upon visiting his city, a sampedrano tells you where the rapings occur as nonchalantly as a Chicagoan points you to the best deep-dish pizza in town. All this is to say: things in Central America are much worse — not less — than they seem.

Whenever I feel myself growing even minutely blasé about the crisis in my maternal homeland, I remind myself of the fate a young girl who, attempting to fend off gang members looking to rob her (and probably more), had her throat slit, her panties stuffed into the hole in her neck, and her body dumped in a ravine where the victims of gang violence and extrajudicial killings by the military-police lay side by side. The story made it to the American mainstream media (in fact I think it, too, was in the New York Times), which suggests accounts such as this one are only the visible tip of a gruesome iceberg.

***

Hector Luis Alamo is a Chicago-based writer and the deputy editor at Latino Rebels. You can connect with him @HectorLuisAlamo.

[…] any of the tens of thousands of refugees scrambling to make it to the Texas-Mexico border each year and they’ll tell you that, for […]

[…] as my friend Hector Luis Alamo wrote in Latino Rebels, “the U.S. government has refused to label them refugees, opting instead to refer to them as ‘migrants,’ a word which implies they’re little more than […]

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.