UPDATE: The popularity of this post has led to several people asking us to add their names to this statement. If you would like to add your name, just go down to the comments section and add your name. Thanks.

EDITOR’S NOTE: A collective of Puerto Rican intellectuals and their fellow supporters, mostly academics teaching in the U.S. and spearheaded by Aurea María Sotomayor (University of Pittsburgh), have put together a statement that they would like friends and associates in the U.S. media to publish, discuss, and disseminate. It is a declaration that, on the one hand, denounces the different legal, political, financial, and logistical predatory forces behind the current “second-class-citizenship” impasse that is increasing the risk and expendability of Puerto Rican lives after Maria’s catastrophic wake. On the other, it is an urgent call to politicians and policy makers to exempt Puerto Rico permanently from the Jones Act and repeal the PROMESA law and other measures and policies that are hampering recovery.

Statement for Puerto Rico

The destruction brought by Hurricane Maria has exposed the profound colonial condition of Puerto Rico, as millions of human beings are faced with a life or death situation. The financial crisis manufactured by American bankers, colonial laws such as PROMESA and the Jones Act that controls maritime space, are legal mechanisms that prevent Puerto Rico’s recovery, and even call into question the validity of American citizenship on that island. Given the severity of the situation, political action is necessary.

The State of Facts

Puerto Rico is experiencing a humanitarian crisis as a result of Hurricane Maria, which struck the island on Wednesday, September 20, as a Category Four hurricane. Immediately thereafter, Governor Rosselló declared a curfew from dawn to dusk for security reasons. Ten days after the event, hundreds of communities are still flooded, isolated without any food or drinking water, as highways and roads are blocked or destroyed, making communication between towns, neighborhoods and cities impossible. Telephone, internet, drinking water and electricity services have not been re-established in most communities. The weather radar was destroyed as well as the surveillance towers at the San Juan International Airport.

There is a public health crisis due to the precarious conditions in hospitals and the threat of epidemics stemming from contaminated water. Cities, towns and neighborhoods outside the metropolitan area have been abandoned, and efforts are concentrated in the San Juan metro area. The western part of the island, for example, lacks minimum services. The images shared with the world by visibly shaken journalists, television anchors, and meteorologists speak of the human drama caused by the disaster. What is missing from many of those reports is concrete information of plans and immediate, achievable initiatives to move the country ahead, as well as an ongoing plan. Explanations are necessary for why so many efforts to reach, house, feed and clothe many Puerto Ricans are unsuccessful. The people and the local government need the freedom to make and act on decisions quickly.

There is no sensible political analysis of the situation due to such dire absence of communication. The state of precariousness in which the entire population of the island finds itself forces individuals to concentrate all of their strength on survival. Many have already opted to leave the country as the re-opening of the Luis Muñoz Marín airport demonstrated in its first day of service after the hurricane. It is a cruel way of emptying Puerto Rico of its most valuable resource, its people; the potential silencing of any dissident voices in the process is unacceptable. This state of emergency could be used to promote new measures of austerity that will not benefit Puerto Rico, a country already devastated by the financial disaster of an unpayable debt.

The Caribbean has been pummeled by two major hurricanes in the month of September: Irma and Maria. The Virgin Islands, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Dominica, Barbuda, Antigua, Guadeloupe, St. Kitts, and Puerto Rico are geopolitically precarious: physically as islands and politically for their colonial history and status. They were traditionally called “Overseas Provinces” because of their political and economic dependence on a metropolitan mainland. The world has found out in the past few days what our history has always stubbornly made visible to us.

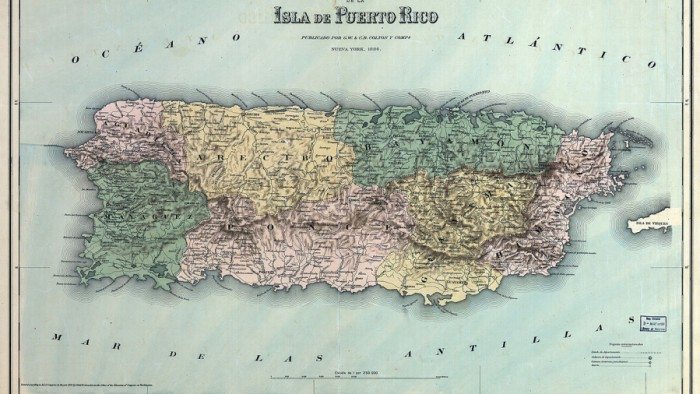

Puerto Rico is a colony of the United States. Its political status stems from the U.S. invasion of 1898 and a series of laws that served only to consolidate U.S. control, hindering the possibility of Puerto Rican sovereignty and political emancipation. One such law is the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, or Jones Act, which determines that Puerto Rico’s maritime waters and ports are controlled by U.S. agencies. The limits on shipping imposed by the Jones Act double the cost of consumer goods arriving at our shores, since they curtail the ability of non-U.S. ships and crews to engage in commercial trade with Puerto Rico. The recent legislation, PROMESA (or “promise,” a cynical and injurious acronym for the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act), which imposes millions of dollars of accrued debt and stringent austerity measures on Puerto Rico and its inhabitants, is yet to be audited.

PROMESA has established a supra governmental body with complete control over finances and the laws and regulations adopted by the PR government. PROMESA represents Congress’ most significant overt act to restate its colonial authority over Puerto Rico in total disregard of democracy, republicanism, and popular sovereignty. Here is where the need to repeal PROMESA and the Jones Act intersect, as both are exercises of colonial power to further the economic and political interest of the metropolis. At this time of humanitarian crisis and dire times for Puerto Rico, Washington must act in the best interest of the people of Puerto Rico by repealing both PROMESA and the Jones Act.

The U.S. citizenship of Puerto Ricans, in this circumstance, is not a privilege, but the branding of a slave. It is a restrictive citizenship subject to the limits imposed by the US Congress without any interpellation of the subject to whom it is imposed. As an American colony, citizenship in this case actually denies Puerto Ricans any of the rights obtained by other regions impacted by the same events in the North American mainland. Citizenship makes us hostages, dispensable entities and victims of calculated charity. It is necessary to repeal the Jones Act, which imposes restrictions on the entry of other vessels to the island, even if their intention is only to offer humanitarian aid. It is necessary to abolish the PROMESA Law, since Puerto Rico cannot be rebuilt on the basis of an unpayable and fraudulent debt. Both laws condemn the country to an unsustainable economic future that will intensify the exodus of Puerto Ricans from their island.

The manner in which aid delivered to Puerto Rico has been confiscated and controlled by FEMA, along with the refusal to assist Puerto Rico in a manner similar to that offered to mainland localities affected by Hurricane Irma, for example, shapes our interpretation of this event. It subjects the inhabitants of a territory in crisis to the limits of what a federal agency is willing to do, and denies aid that may come from other countries at this critical time. Beyond the paternalism that this implies, it turns Puerto Ricans into hostages of their colonial condition.

While exploiting the physical deprivation Puerto Ricans are experiencing, FEMA’s presence also promotes psychological servility. As military uniforms increase and become more visible due to this emergency, a very troubling image is emerging of the Puerto Rican people, under increasingly fragile and precarious conditions. Efforts are delayed for a population that the federal government considers expendable. Rampant indifference is affirmed with lack of solidarity with neighboring towns by preventing other kinds of aid from flowing into and through the island.

This situation brings Puerto Ricans down to their knees, at the mercy of the equivocal aid provided by the U.S., while other humanitarian aid is blocked. Puerto Ricans are placed under peril, endangering the lives of thousands that still have not been reached. The ultimate goal of this federal aid is unknown. Its growing militarization at a time when Puerto Ricans are deprived of the basic means of survival and communication is alarming. It turns this state of emergency into an opportunity for some to thrive financially while hundreds of people die from lack of water, food and medical treatment. No political or economic reason justifies the death of diabetes patients who do not have the means to keep their insulin cool nor dialysis patients who have seen their treatments interrupted due to lack of electricity. The consequences of this blockade on solidarity could be greater than the victims produced by the hurricane itself. The recent statements by President Trump are unworthy of any president. In the midst of a humanitarian crisis, he demands payment of the credit debt. Immediate actions must be taken. The PROMESA law and the Jones Act must be repealed. This is not the time to invoke the false rights inherent in second-degree citizenship, but to claim the right of every human being to life.

Faced with these facts, we demand:

- The recognition of a state of humanitarian crisis.

- The immediate repeal of the Jones Act (Merchant Marine Act of 1920) for Puerto Rico and the repeal of the PROMESA Law.

- That the aid provided by the federal agencies not be subjected by any conditions that can delay or limit its reach.

- The opening of the ports to all those who wish to show solidarity with the Puerto Rican people.

- The reestablishment of all means of communication across the island.

- Dedicated funds and assistance for the thousands of people without home, water, food, and electricity.

Declaración por Puerto Rico

La destrucción causada por el Huracán María ha develado aún más la condición colonial de Puerto Rico, donde millones de personas se enfrentan hoy a una lucha entre la vida y la muerte. La crisis financiera creada por la banca norteamericana y leyes coloniales tales como PROMESA y el Acta Jones (Leyes de Cabotaje de 1920) son mecanismos legales que impiden dicha recuperación, poniendo en tela de juicio el valor mismo de la ciudadanía americana en la isla. La urgencia de la situación requiere una respuesta política.

El estado de hecho

Puerto Rico está atravesando una crisis humanitaria como consecuencia del huracán María, que asoló la isla el miércoles, 20 de septiembre, como un huracán de categoría cuatro. Inmediatamente, por razones de seguridad, el gobernador declaró un toque de queda de siete a seis de la tarde, que continúa vigente indefinidamente. Diez días después del evento, todavía cientos de comunidades se hallan aisladas e inundadas, carentes de alimentos y agua potable por razón de la destrucción de las autopistas y carreteras, sumiendo en la incomunicación a pueblos, barriadas y ciudades. Tampoco se han restablecido los servicios de telefonía, internet, agua potable ni electricidad en la mayor parte del país. El radar meteorológico está destruido, así también como las torres de vigilancia del aeropuerto internacional.

Existe una crisis de salubridad pública, dadas las condiciones precarias en los hospitales y la inminencia de epidemias a causa de la contaminación de las aguas. Ciudades, pueblos y barriadas fuera del área metropolitana han sido abandonados y los esfuerzos se concentran en San Juan. El área oeste, por ejemplo, carece de los servicios mínimos. Las imágenes compartidas por los medios de prensa muestran a periodistas y meteorólogos conmovidos con el drama humano ocasionado por el desastre.

Lo que aún no se discute en dichos reportajes es un plan coherente de acción a corto y largo plazo para mover al país hacia adelante, especialmente respecto a lo que más urge. Tampoco parece existir un plan de mitigación y no se aducen las razones de la falta de circulación de provisiones y ropa. Se desconoce hacia dónde se dirige el país. Inmersos en el espacio de la precariedad, la fuerza se concentra en la sobrevivencia y aún no es visible un análisis sensato de naturaleza política de la experiencia que se vive al presente. Muchos ya han decidido abandonar el país, como se demostró el primer día en que se abrió el aeropuerto internacional. Es una imagen cruel en donde contemplamos cómo la urgencia de la situación y la ausencia de un plan de acción inmediata vacían al país. El peor resultado sería el silenciamiento de cualquier voz disidente. Las medidas de emergencia han creado un estado de excepción, útil para impulsar normas de austeridad que en nada benefician a Puerto Rico, un país ya devastado por el desastre financiero de una deuda impagable.

Las islas que conforman la cuenca del Caribe han sufrido los embates de dos fuerzas huracanadas mayores en el mes de septiembre: Irma y María. Las islas de Cuba, República Dominicana, Dominica, Barbuda, las Islas Vírgenes, Antigua, Guadalupe, St. Kitts y Puerto Rico son estados política y geográficamente precarios, por razón de su condición de isla y por su condición política colonial. “Provincias de ultramar” se las llamaba, por razón de su dependencia política con respecto a un territorio metropolitano. El mundo ha contemplado en estos días recientes lo que la historia ya ha hecho evidente ante nuestros ojos: nuestras fronteras marítimas y aéreas son controladas por agencias norteamericanas.

Puerto Rico es una colonia de los Estados Unidos, cuyo vínculo político emana de una invasión después de la cual se impuso la ciudadanía norteamericana, y una secuela de leyes que solo sirven para consolidar el vínculo servil y lastrar la posibilidad de la soberanía y la emancipación. La ciudadanía norteamericana tuvo como secuela inmediata el reclutamiento de puertorriqueños en el servicio militar obligatorio durante las guerras mundiales, así como la Ley Jones sirve para controlar y duplicar el costo de los bienes materiales que llegan a puerto, pues solo barcos norteamericanos están legitimados comercialmente.

La reciente ley PROMESA (un acrónimo cínico e injuriante que designa las siglas de una junta de acreedores) y que le impone a Puerto Rico y sus habitantes el pago de millones de dólares y medidas extremas de austeridad ni siquiera se ha auditado. PROMESA se ha convertido en un cuerpo supra gubernamental con control absoluto sobre las finanzas, las leyes y los reglamentos vigentes en Puerto Rico. PROMESA es el acto congresional más oneroso que ratifica la autoridad colonial sobre Puerto Rico y constituye una expresa violación de los principios de la democracia, el republicanismo y la soberanía popular. En ello estriba la necesidad de derogar PROMESA y la Ley Jones, pues en su convergencia jurídica coagula el dominio del poder colonial con el propósito de conservar y avanzar los intereses económico-políticos de la metrópolis. En este momento, cuando prevalece una crisis humanitaria en Puerto Rico, no existe un ápice de interés que mueva a Washington a derogar permanentemente ambas leyes a fin de que redunde a favor de los intereses del pueblo puertorriqueño en estos tiempos aciagos.

La ciudadanía norteamericana, en estas circunstancias, no es un privilegio, sino un carimbo impuesto al esclavo para marcarlo, de forma que rinda con su cuerpo un débito extraño bajo las circunstancias más acuciantes. Se trata de una ciudadanía precaria, sujeta a los límites que el Congreso precisa, sin ninguna interpelación del sujeto a quien se le impone. En estas circunstancias, ser una colonia norteamericana y ser ciudadanos de los EEUU no concede ninguno de los derechos obtenidos por zonas impactadas por los mismos sucesos en territorios norteamericanos. Todo lo contrario. Más bien, la ciudadanía nos convierte en rehenes, en entes prescindibles y en víctimas de una caridad calculada. Es necesario abolir el Acta Jones, que impone restricciones de ingreso de otros buques a la isla, siquiera para tender una mano solidaria. Es necesario abolir la Ley PROMESA, pues Puerto Rico no puede reconstruirse sobre la base de una deuda impagable y fraudulenta. Ambas leyes condenan al país a un futuro económico insostenible que intensificará el éxodo de los puertorriqueños fuera de su isla.

La “ayuda” controlada hasta este momento por los Estados Unidos a través de FEMA transforma las coordenadas de interpretación de este evento. En primer lugar, porque somete a los habitantes de un territorio en crisis a lo que pueda realizar una agencia federal, excluyendo la ayuda que pueda provenir de otros países en este momento crítico. Más allá del paternalismo que ello implica, convierte a los puertorriqueños en rehenes de su condición colonial. Al explotarse el momento de precariedad física por la que pasan, promueve el que devenga servilismo psicológico. Hay que preocuparse por la imagen del puertorriqueño que puede crearse a partir de esta emergencia, ahora que más frágil y precarias son las condiciones, mientras incrementan y se tornan más visibles los uniformes.

Se propicia el chantaje sentimental, se demora el esfuerzo ante una población que el gobierno federal considera prescindible y se confirma la indiferencia con el cercenamiento de la solidaridad con otros pueblos hermanos al impedirse que fluya otro tipo de ayuda.

Se reduce al puertorriqueño al “amparo” de un país, se bloquean otras ayudas humanitarias, se le coloca al borde de la desaparición arriesgando la vida de miles que aún se hallan incomunicados.

Se desconoce el fin último de este toldo de ayuda federal. La creciente militarización de dicha ayuda humanitaria en un momento en que los puertorriqueños están absolutamente incomunicados y desprovistos no anuncian un futuro claro.

Torna la inminente transformación de este estado de emergencia en una oportunidad para medrar económicamente, mientras cientos de personas mueren por falta de agua, alimentos y tratamiento médico. Ninguna razón política o económica justifica la muerte de pacientes de diabetes que no poseen los medios para enfriar sus dosis de insulina ni la de pacientes de diálisis que han visto sus tratamientos interrumpidos por falta de electricidad. Las consecuencias de este bloqueo a la solidaridad podrían ser mayores que las víctimas producidas por el huracán mismo. En medio de una crisis humanitaria, el Presidente insiste en ratificar y exigir el cumplimiento del pago de la deuda crediticia. Ante su posición, es necesario acudir a otros medios. Es preciso abolir la Ley PROMESA. No es hora de invocar los falsos derechos inherentes a una ciudadanía de segundo grado, sino clamar por el derecho de todo ser humano a la vida.

Ante esta situación de hechos, exigimos:

- el reconocimiento de un estado de crisis humanitaria.

- la derogación inmediata del Acta Jones (Ley de la Marina Mercante de 1920) para Puerto Rico y de la Ley PROMESA.

- no condicionar la ayuda provista por las agencias federales.

- la apertura de los puertos a todos los que deseen solidarizarse con el pueblo puertorriqueño.

- el restablecimiento de todos los medios de comunicación por tierra de toda la isla.

- fondos y asistencia para los miles de personas sin casa, agua, alimentos y servicios de electricidad.

Firmantes-Signatures

Áurea María Sotomayor Miletti, University of Pittsburgh

Juan Carlos Rodríguez, Georgia Tech University

Sheila I. Vélez Martínez. University of Pittsburgh

Myrna García Calderón, Syracuse University

María de Lourdes Dávila, New York University

Nemir Matos Cintrón, Ana G. Mendez, Florida Adriana Garriga López, Kalamazoo College

Luis Othoniel Rosa, University of Nebraska

César A. Salgado, University of Texas, Austin

Lena Burgos Lafuente, Stony Brook University

Kahlil Chaar-Pérez, Editor and independent translator

Rubén Ríos, New York University

Julio Ramos, University of California, Berkeley

Arnaldo Cruz Malavé, Fordham University

Jossianna Arroyo, University of Texas, Austin

Miguel Rodríguez Casellas, University of Technology

Sydney Licia Fiol-Matta, New York University

Juan Carlos Quintero-Herencia, University of Maryland

Dafne A. Duchesne Sotomayor, Rutgers University, New Brunswick

René A. Duchesne Sotomayor, Junior Architect, Pittsburgh

Margarita Pintado Burgos, Ouachita, Baptist University

Kelvin Durán Berríos, University of Pittsburgh

Edgard Luis Colón Meléndez, University of Pittsburgh

Gustavo Quintero, University of Pittsburgh

Urayoán Noel, New York University

Jaime Rodríguez Matos, California State University, Fresno

María Dolores Morillo López, California State University, Fresno

Ivette Romero, Marist College

Rocío Zambrana, University of Oregon

César Colón Montijo, Columbia University

Ivette N. Hernández-Torres, University of California at Irvine

Yolanda Martínez-San Miguel, University of Miami/Rutgers University

Wanda Rivera-Rivera, Brearley School, New York

James Cohen, Université Paris 3, Sorbonne Nouvelle

Nayda Collazo Lloréns, Kalamazoo College, Michigan

Cristina Moreiras-Menor, University of Michigan

Odette Casamayor, University of Connecticut, Storrs

José Quiroga, Emory University

Cristel Jusino Díaz, New York University

Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes, University of Michigan

Eliseo Colón Zayas, University of Puerto Rico

Nelson Maldonado-Torres, Rutgers University, New Brunswick

Pamela Voekel, Dartmouth College

Diana Taylor, New York University

Alejandra Olarte, Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá

Jasón Cortés, Rutgers University, Newark

Yara Liceaga, Writer and Cultural Activist

Diana Guemarez Cruz, Montclair University

Luis F. Avilés, University of California, Irvine

Ramón López, Hunter College

Carina del Valle Schorske, Columbia University

Pablo Delano, Trinity College

Arlene Dávila, New York University

Néstor E. Rodríguez, University of Toronto

Efraín Barradas, University of Florida, Gainsville

Raquel Salas Rivera, University of Pennsylvania

Ronald Mendoza de Jesús, University of California

Iván Chaar-López, University of Michigan

María R. Scharrón-del Río, Brooklyn College, CUNY

Miguel Luciano, Artist

Monxo López, Hunter University

Guillermo Irizarry, University of Connecticut

Myrna García-Calderón, Syracuse University

Cecilia Enjuto Rangel, University of Oregon

Iván Chaar-López, University of Michigan

Manuel G. Avilés-Santiago, Arizona State University

Ángel Rivera, Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Claudia Sofía Garriga-López, New York University

Mónica Alexandra Jiménez, University of Texas, Austin

Reynaldo Padilla, University of Puerto Rico

Mónica E.Lugo-Vélez, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

Luis J. Cintrón-Gutiérrez, University at Albany/SUNY

Jorell A. Meléndez-Badillo, University of Connecticut, Storrs

Jonathan Montalvo, Graceland University

Sandra Casanova, Binghamton University

Diana Guemárez-Cruz, Montclair State University

María del Mar González, Independent Scholar

Alai Reyes Santos, University of Oregon

Nayda Collazo-Lloréns, Kalamazoo College

Isa Rodríguez-Soto, University of Akron

Marcela Guerrero, Whitney Museum of American Art

Vanessa Arce Senati, University of Buffalo

José G. Luiggi-Hernández, Duquesne University

Moisés Agosto-Rosario, Director of Treatment at NMAC, Washington DC

Patricia Villalobos Echeverría, Western Michigan University

Christina A. León, Princeton University

Frances Aparicio, Northwestern University

Beliza Torres Narváez, Augsburg University

Judith Sierra-Rivera, The Pennsylvania State University

Joshua G. Ortiz Baco, The University of Texas, Austin

Lcdo. Gabriel E. Laborde Torres, Goldstein & Associates Cristina Pérez Jiménez, Manhattan College

Jorge Irizarry Vizcarrondo, J. D.

Nicole Cecilia Delgado, La Impresora

Cristina Pérez Jiménez, Manhattan Colege

Santa Arias, University of Kansas

Daniel Nevarez, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Sally A. Everson, University of the Bahamas

Aurora Santiago-Ortiz, J.D. University of Massachusetts

Valeria Grinberg Pla, Bowling Green State University

Joseph A. Torres-González, City University of New York

Marco A. Martínez Penn State University

Jessica Mulligan, Providence College

José Martínez-Reyes, University of Massachusetts, Boston

Halbert Barton, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Long Island University

José R. Irizarry, Villanova University

Jorell A. Meléndez-Badillo, University of Connecticut, Storrs

Isatis M. Cintrón, Rutgers University

Karrieann Soto Vega, Syracuse University

José R. Días-Garayúa, California State University Stanislaus

Marisol LeBrón, Dickinson College

Giovanna Guerrero-Median, Yale Ciencia Initiative, Puerto Rico

Agustín Laó-Montes, University of Massachusetts at Amherst

Luis J. Beltran Álvarez, University of Connecticut, Storrs

Shariana Ferrer-Núñez, Purdue University

Catalina de Onís, Willamette University

Selma Feliciano-Arroyo, University of Pennsylvania

Emma Amador, Brown University

Frances Negrón-Muntaner, Columbia University

Liza Goldman Huertas, MD, West Haven, CT

José Quiroga, Emory University

Carlos Gardeazábal Bravo, University of Connecticut

Alexa S. Dietrich, Wagner College

Maritza Stanchich, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras

Don E. Walicek, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras

Yadira Pérez Hazel, University of Melbourne

Salvador Vidal-Ortiz, American University

Carlos E. Rodríguez-Díaz, Universidad de Puerto Rico-Recinto de Ciencias Médicas

Stephanie Mercado Irizarry, University of Connecticut, Storrs

Libertad Guerra, Director of the Loisaida Cultural Center

Alfredo Villanueva-Collado, CUNY

Joaquín Villanueva, Gustavus Adolphus College

Laura Briggs, University of Massachusetts

Maximilian Alvarez, University of Michigan

Ivonne del Valle, University of California, Berkeley

Francisco Cabanillas, Bowling Green State University

Jason Ortiz, Hartford CT, President CT Puerto Rican Agenda

Carlos Amador, Michigan Technological University

Karen Graubart, History, University of Notre Dame

Raul Santiago Bartolomei, University of Southern California

Sol Price, School of Public Policy, University of South California

Oscar Ariel Cabezas, UMCE, Santiago de Chile

Féliz Padilla Carbonell, University of Connecticut

Juan Sánchez, Hunter College, CUNY

Laura Marina Boria González, University of Texas at Austin

Daniel Torres Rodríguez, Ohio University

Anne Garland Mahler, University of Virginia

Vanessa Pérez-Rosario, Brooklyn College/CUNY

Jean Carlos Rosario Mercado, City University of New York

Carlos J. Carrión Acevedo, Universidad de Puerto Rico

Ryan Mann-Hamilton, CUNY Laguardia

José R. Díaz-Garayúa, California State University, Stanislaus

Juana Goergen, De Paul University

Pepón Osorio, Temple University

Ingrid Robyn, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Carlos Fonseca, Cambridge University

Jacqueline Loss, University of Connecticut

Pamela Cappas-Toro, Stetson University

Michelle Osuna-Díaz, KIPP Austin

Kristina Medina, St. Olaf College

Jennifer S. Hughes, University of California, Riverside

Jorge Matos- Valdejulli, Hostos Community College, CUNY

Mariana Cecilia Velázquez, Columbia University

Carmen Rabell, Universidad de Puerto Rico

Pedro López Adorno, Hunter College

Luis J. Cintrón Gutiérrez, University at Albany, SUNY

Idania Miletti, Orlando, Florida

Javier Román Nieves, Yale School of Forestry

Kaliris Y. Salas Ramírez, CUNY School of Medicine

María M. Carrión, Emory University

Stephanie Mercado, University of Connecticut

Arturo Arias, University of California, Merced

Cristián Gómez Olivares, Case Western University, Ohio

John Beverley, University of Pittsburgh

Ana Dopico, New York University

Irizelma Robles, Universidad de Puerto Rico

Mónica Barrientos Olivares, Universidad de Chile

Roger Santibañez, Temple University

Eddie S. Ortiz, Bike Courier

Ivette Román Roberto, Artist

Malena Rodríguez Castro, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras

Sally Everson, University of The Bahamas

Jorell Meléndez Badillo, University of Connecticut

Elizabeth Monasterios, University of Pittsburgh

Daniel Balderston, University of Pittsburgh

Tania Pérez Cano, University of Massachusetts

Dartmouth Dolores Lima, University of Pittsburgh

Mariela Dreyfus, New York University

Jerome Branche, University of Pittsburgh

Karen Goldman, University of Pittsburgh

Gonzalo Lamana, University of Pittsburgh

Daynalí Flores Rodríguez, Illinois Weslean University

Cynthia Román, Latin American Association, Atlanta

Rosa M. Connor Acevedo, Williams College

Eyda M. Merediz, University of Maryland, College Park

Iliana Pagán, West Chester University

Nicole Delgado, La Impresora

Sergio Gutiérrez Negrón, Oberlin College

Ronald Mendoza-de Jesús, University of South California

Yomaira Figueroa, Michigan State University

Joshua Ortiz Baco, University of Texas, Austin

Mario Mercado Díaz, Rutgers University

Carla Acevedo-Yates, Michigan State University

Frances Aparicio, Northwestern University

Luis Aponte, University of Massachusetts, Boston

Miguel Cruz-Díaz, Indiana University, Bloomington

Ricardo Monge, Artist

Marina Reyes Franco, Curator

Bianca Premo, Florida State University, History

Talía Guzmán González, University of Maryland

Jara Rios, University of Wisconsin

Yasmin Ramirez, Hunter College, CUNY

Mark Schuller, Northern Illinois University

William García

Nilvea Malavet

Karen Cresci, UnMdP-CONICET

Cecilia Palmeiro, NYU BA

Mara Mahía, Writer and Independent Journalist

Wadda C. Ríos-Font, Barnard University

Harry Vélez, University of Puget Sound

Roberto Castillo Sandoval, Haverford College

Gabriel Giorgi, New York University

Claudia Salazar, Brooklyn College/NYU

Luz M. Betancourt

Bobby Rivera, St. John University

Aixa Méndez

Alicia Díaz, University of Richmond

Ben Sifuentes-Jáuregui, Rutgers University

Miriam Margarita Basilio, Art History and Museum Studies, NYU

Eri Saikawa, Emory University

Lynne Huffer, Emory University

Angelika Bammer, Emory University

Natalie Belisle, University of Southern California

Juan Sánchez, Hunter College, CUNY

Melanie Pérez Ortiz, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Diana Aldrete, Trinity College

Willmai Rivera Pérez, Southern University

Joanna Marshall, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Cayey

Mara Pastor, Pontificia Universidad Católica, Ponce

Alexandre Alaric, Université des Antilles

Nancy Calomarde, Universidad de Rosario

Yvonne Sanavitis, Universidad de Puerto Rico

Enid Álvarez, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras

Nadia Prado, Writer, Chile

Rafael Acevedo, Writer, Universidad de Puerto Rico

José Punsoda Díaz, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras

Rosario Caicedo, Connecticut

Leonardo E. Carrero, TD Bank

Sebastián Urli, Bowdoin College

Roberto Castillo Sandoval, Haverford College

Anabel López-García, New York University

Claudia Salazar, Brooklyn College

Alma Concepción, Artist, New Jersey

Isolda Ortega Bustamante

Jaime Dávila, Hampshire College

Luz M. Betancourt, Artist, New York

Alicia Díaz, University of Richmond

Bobby Rivera, Saint John’s University, NY

Leonardo E. Castro Martínez, TD Bank

Yoryie Irizarry, Lawyer, NY

Melinda Andorínha González

Sonia Labrador Rodríguez, New College of Florida

Alicia Ortega, Universidad de Quito, Ecuador

Ana Ramos Zayas, Yale University

Rebecca Mundo, INBA, CENIDID, Danza

José Limón, INBA, México

John Torres, Writer, Puerto Rico

Manuel S. Almeida, Teórico Político, San Juan

Marla Pagán Matos, Universidad de Puerto Rico

Javier Contreras V., Centro de Investigación Coreográfica, INBA, México

Margarita Saona, University of Illinois, Chicago

Taína Figueroa, Emory University

Jacques Lezra, University of California, Riverside

Tracy Scott, Emory University

Munia Bhaumik, Emory University

Luis Girón Negrón, Harvard University

Lourdes Martínez Echazaval, University of California, Santa Cruz

Abraham Acosta, University of Arizona

Minerva Cordero Braña, University of Texas at Arlington

Manuela Ceballos, University of Tennessee

Melinda Robb, Emory University

Cathare Ngoh, Emory University

Megan Saltzman, West Chester University

Sean Meigoo, Emory University

Pat Meisteller, Emory University

Sonia Báez Hernández, Artist, Miami, Florida

José Calvo, Law Professor, Universidad de Sevilla

Marisol Negrón, University of Massachusetts, Boston

Michael Rodríguez Muñiz, Northwestern University

Ana Aparicio, Northwestern University

Debb Vargas, Rutgers University

Curtiz Marez, University of California, San Diego

Alberto Rodríguez, Dickinson College

Elizabeth Davis, Ohio State University

Julie Skurki, CUNY

Joanna Marshall, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Cayey

Robert F. Alegre, University of New England

Elizabeth Oglesby, University of Arizona

Rosa O’ Connor Acevedo, University of Puerto Rico

Ana Irma Rivera Lassén, Lawyer, San Juan, Puerto Rico

María Elba Torres Muñoz, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras

Miguel Valderrama, Universidad de Chile

Magali García Ramis, Writer, San Juan

Elizabeth Robles, Artist and Writer, San Juan

Rodrigo Karmy, Universidad de Chile

Medzouar El Idrissi, Universidad Abdelmalek Essaudi, Tetuán, Tánger

León Félix Batista, Writer, Dominican Republic

Kenya C. Dworkin y Méndez, Carnegie Mellon University

Ana Longoni, CONICET, Universidad de Buenos Aires

María Collazo Rivera, Universidad de Puerto Rico

María Julia Dávila Collazo, Geographer, Puerto Rico

Efrén Collazo Rivera, Premier Homes Realty, PR

Domingo Dávila, Retiree, Puerto Rico

Roadney Rivera, Universidad de Puerto Rico

María Fernanda Pampín, Universidad de Buenos Aires, CONICET

José Olmo, Boricua College, NYC

Rafael Texidor Robles, Lawyer, San Juan, Puerto Rico

Mercedes Roffé, Writer, New York

Dante del Águila, Actor, Perú

Mario Biagini, Grotowski and Tomás Richards Workcenter, Italy

Eduardo Lalo, Writer, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras

Christiane Leon Robbins, USC

I always believed when I was a young girl, raised in Ca, with Puerto Rican parents that,Puerto Rico was always just receiving charity from U. S. , neither this nor that , neither here or there. It must fight to stand on its own. The island has not benefited anything from U.S, on the contrary it’s become a horror .Iam now close to retire, Soo, sad to see that nothing has changed. It’s like a child , must be emancipated. What’s there left to lose?

To continue my life in Puerto Rico I have invested in a good size generator, storm protectors, smoke detectors, gas power systems for energy. I have spent $18, 000.00 to be able, until the end of my days, to live a tranquil life in my hurricane infectected island. This, together with high sales tax, income tax, high prices and terrible electric system, bad roads and bad water systems will provide a burdened quality of life during my last days in my island.