Students and teachers have taken center stage in the first half of 2018—in their public fights for protection from gun violence, in their rallies against wage inequities, and for a continued fight for an education and curriculum that critically reckons with historical truths and fallacies. Worldwide, students have often been at the forefront of social movements. This May 11, marks the 25th anniversary of the arrest of 99 students at UCLA who formed part of the Chicana/o Studies Now Movement—a movement that galvanized both the campus and city community and one that was defined by an era of many social setbacks in the state of California that included state propositions 209, 227, and 187. Drawing lessons from this struggle is pertinent today.

In the spring of my sophomore year at UCLA, the administration threatened to close the Chicana/o Research Library. Students planned an act of civil disobedience—a take-over and sit-in at the campus Faculty Center. I was eager to join, but was scheduled to work that morning. I asked my boss for permission to miss work to attend the rally. She looked me square in the eye and said yes, on two conditions: Don’t get your picture taken. And don’t get arrested.

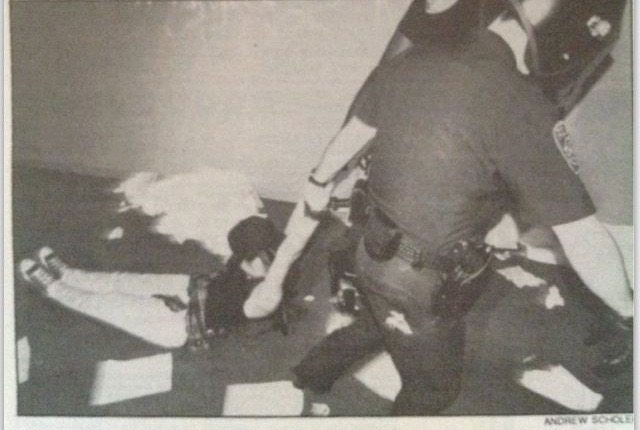

The next morning THIS photo was on the cover of the METRO section of the LA Times and I was in custody at the downtown Los Angeles county jail, along with 98 of my student peer activists.

The Los Angeles Police Department arrived (not the campus police) and, after several threats of removal, dragged us out, arrested us, and charged us with felony vandalism.

That night I was forced to do a cavity strip search, was given a bail that my family could not meet (even if I had called them) and was put into a maximum security unit at the now defunct Sybil Brand Institute for Women.

Within 48 hours, we were all released and greeted by a sea of supporters outside of the jail.

Following our arrests, the university sent us a letter, threatening expulsion. In my case, while the charges against me were eventually dropped, I had to attend a court hearing and was placed on a one-year probation by the judge who heard my case. While the university rescinded its threat of expulsion, it was clear that falling ‘out of line’ in the next year would be met with serious consequence.

All of this was frightening, but facing my family was the most difficult. My father, who worked three jobs and died nine months after my arrest, was so disappointed. He initially couldn’t comprehend why I would risk my future for this issue. Similarly, I’ll never forget watching the incredulous look on my mom’s face when I told her about my arrest.

“Y todo el sacrificio que hemos esfuerzado (what about all of our sacrifice),” she said.

“Es por eso mismo que lucho (this is why I fight),” I responded.

This is a painful memory but an important marker in my turn towards public advocacy.

The faculty center sit-in led to a subsequent 14-day hunger strike. Ultimately, this led to an agreement between the UCLA administration and student activist leaders, creating the César E. Chávez Research Center. It took more than a decade, but in 2005, the department was finally established. Today, more than 500 students are part of the Chicana/o Studies department (200 as majors, 300 as minors, 30 pursuing Ph.Ds.).

Certainly, this is a moment to celebrate. However, the 25th anniversary of our initial action —one that could have ended all of our academic trajectories— causes me to pause, as a scholar and writer of Chicana/x Studies, to reflect on some of the lessons of that movement and to recognize how my participation in the Chicana/o Studies Now Movement greatly shaped my political formation and informed my commitments as a writer and scholar-activist. It reminds me how the student and teacher activism taking place now is likely to transform its participants and their lives for years to come. For me, it changed my understanding of the world in matters far beyond saving a library.

Student activism is where I found my public voice when I picked up my first megaphone and yelled ‘Chicana!’ My call was met with a resounding ‘Power’ as we walked across the quad on our campus. The movement itself was rooted in an intersectional analysis, a place where many students of color on campus organized together towards an immediate, common goal that we remained strategically focused on until the demands were met. Women of color were central to the leadership.

A group called Conscious Students of Color drew me in, but there had been a longer history of student organizing by MEChA and community leaders who had been working towards establishing a Chicana/o Studies department on campus well before our first action The movement was cross-sectional as labor unions, cultural leaders and community members came out in droves to marches, our rallies and by weighing in publicly on the media. This movement taught me about transnationalism because it recognized migration as an inherent human right; those of us who stayed behind had to watch some of our peers leave the action out of fear of being deported if they were arrested. It introduced me to the concept of abolition, especially as I sat in the maximum security unit with women who had committed violent crimes but who had also been the victims of assault and abuse for much of their lives. The battle for Chicana/o Studies also taught me about decolonization and indigenous peoples rights, helping me to learn a history that had been denied to me and to recognize my own ancestral ways of being.

Moreover, the CCS Now movement was a lesson on power—on how power can be shifted, on how power can envelope entire communities and on how power insidiously works its way into democratic spaces. Maneuvering this propelled all of us into a radical consciousness that was impossible to forget as we continued our education. Had we all been expelled, there would certainly be a void in the absence of the dynamic individuals who remained committed to challenging power as teachers, lawyers, professors, organizers, cultural workers, community leaders, and artists. I think about the young people on the streets, the teachers at state capitols, and the educators today who are still fighting to insert our narratives into the curriculum and all the ways in which they are met with resistance from institutions, their communities and even their families. While situated differently, not to be conflated, transgressing familial, social and political expectations is a radical act of courage and self-determination.

Elsewhere I have argued that I’ve felt embattled by an academic institution that primarily values Western histories and knowledge systems, which have little to do with my own epistemological position. And that the Chicana/o Studies curriculum created out of struggle has become co-opted into a neoliberal model that defines success not by the lives we are saving, empowering, and making visible but instead by career success, the reification of culture and peoples, and the dollars one brings in to the university. As a professor in a Mexican-American Studies department, this personal and collective anniversary, coupled with today’s student activists, are reminders that our work matters, that our work isn’t done and that the compulsion for ever-evolution must remain close to the commitments we have. Essentially it requires a constant recommitment to our students and communities. As my mom used to say, ‘no quites el dedo del tapón.’ If anyone has a good translation for that, let me know.

Note: Please see the work of Jose M. Aguilar-Hernandez and Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval for more of a historical and sociological analysis of student movements for ethnic studies programs in the nineties in California and their broader impact. Also note that there is a convergence scheduled for this year to commemorate and bring together those 99 students who were arrested. Please visit this page for more information.

***

Michelle Téllez is an Assistant Professor in the department of Mexican-American Studies at the University of Arizona and a public voices fellow at the Op Ed Project. You can follow her on twitter @mtellezphd and learn more about her work at www.michelletellez.com

An important testimonio for the Movement archives! It reminds me of the action that was taking place at the same time at Stanford with very different strategies and outcomes. It would be interesting to have someone do a comparative study of the two actions.