Latino Rebels is running a series of pieces by local Bakersfield journalist/writer Nicholas Belardes about the in-custody death of David Sal Silva. This is the series’ third post. You can read “Part One: Culture of Drugs” here, and “Part Two: Culture of Violence” here. (All photos here should be credited to Nicholas Belardes.)

Part Three: Analysis Of A Protest

BAKERSFIELD, CA – What is it about our society that a few determined people in coordination with common ideologies, pens and poster boards —or even a slab of flat-sided Styrofoam— can create and hold signs on a sweltering street corner, and just might instill change? Or at least hope to.

Protesters across America make signs, from Tea Party fans writing “Obama Liar And Chief” to a man named Brad Belcher in Marion, Ohio, who in February was caught putting up 800 signs around the city that read “Heroin Is Marion’s Economy.”

He was caught in the middle of the night and cited, though his message rang far and wide.

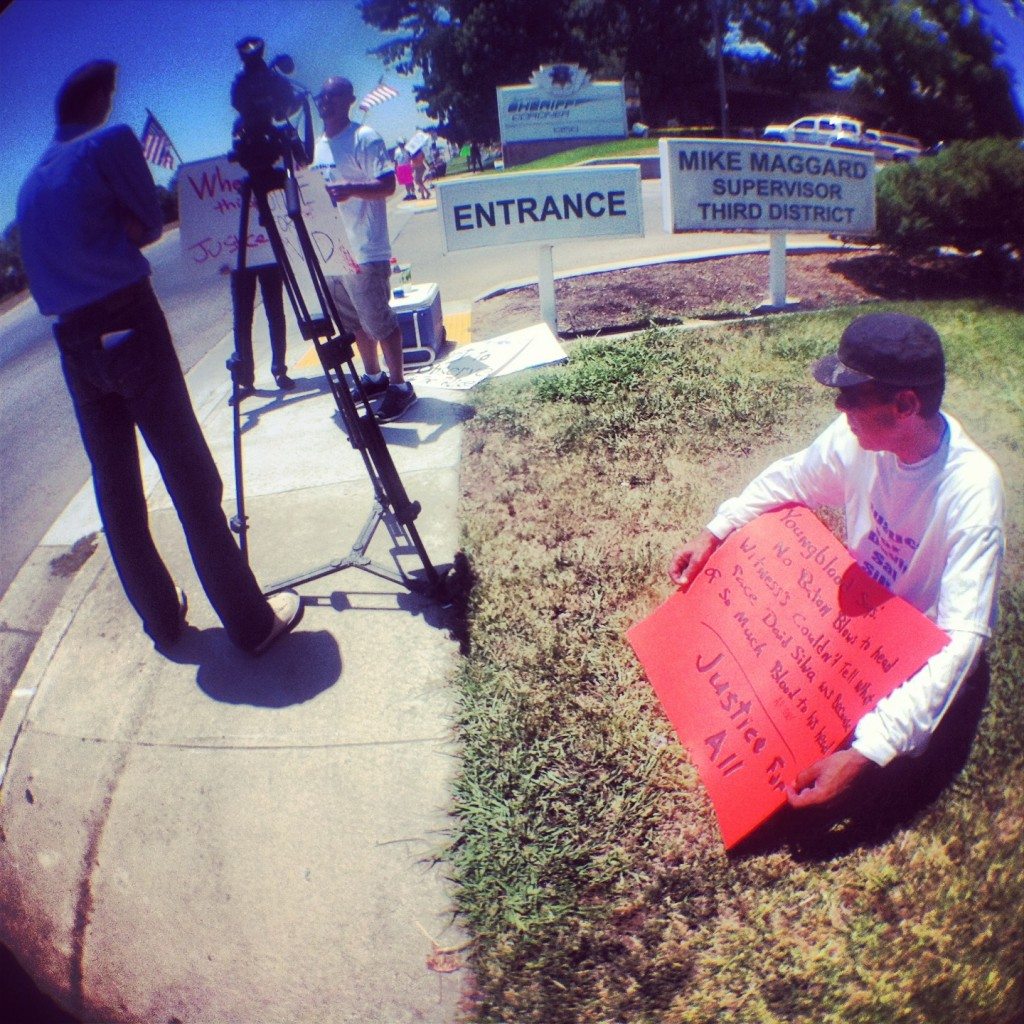

I purposely waited a few days after the rally outside the Kern County Sheriff’s Office on Saturday, June 8, so I could spend some time thinking about the afternoon the Silva family spent protesting in the sweltering 106-degree heat with their myriad of protest signs.

What had I seen? What had I learned? What side should I be on regarding the in-custody death of David Sal Silva that occurred one month prior? What were the signs telling me? Would there be more rallies? More discussion? Could there ever be a citizen-review board in Bakersfield to oversee law-enforcement-related deaths?

It was so hot outside that day that I wondered whether the Silva family would give up in their quest to seek answers, and melt away into another Bakersfield summer.

Harvard historian Bernard Bailyn in his 1990 book, Faces of Revolution, wrote that “in important ways it [the American Revolution] was the product of human decision and the impact of personalities and ideas upon the events of the time.”

In a way, Bailyn was just talking about change. Any kind of social or political transmutation. Revolution means change, upheaval. And if you want to enact change you have to have significant, meaningful events and personalities who will take the time and energy to impact all of it.

So, I ask myself, what is the significance of David Silva’s death? What kind of major event was his passing, and what is the impact of personalities and ideas in relation to his altercation with law officials?

Family and strangers with common interests have bonded together over his death. They have lent voices, support, and many words on poster boards at protests.

Those poster boards created on Saturday were held toward Norris Road. Ironically, they were not aimed physically at the sheriff’s station but away from it, as if to say, “We’ve said enough to law officials, now we want to tell you, society.”

There were many posters, with varying phrases, words, and even a map of the world held by David’s half Navajo-half Caucasian mother, Merri.

Camila Chávez was also in attendance, representing the Dolores Huerta Foundation. In 1988, Dolores Huerta, co-founder of the United Farm Workers, was a victim of brutality by the San Francisco Police Department in front of the Sir Francis Drake Hotel in Union Square. She’d been protesting peacefully.

George Orwell wrote in the late 1940s about something not too unlike a rally or protest poster: the pamphlet. He was quoted in Bailyn’s Pulitzer and Bancroft Prize-winning book The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967 and an expanded edition in 1992) for criticizing British media while also using the idea of pamphleteering in the pre-Revolution-era as examples that could instill change, and really get points across to masses of people. You could interchange the word “poster” for “pamphlet” in this Orwell quote.

The pamphlet is a one-man show. One has complete freedom of expression, including, if one chooses, the freedom to be scurrilous, abusive, and seditious; or, on the other hand, to be more detailed, serious and “highbrow” than is ever possible in a newspaper or in most kinds of periodicals . . . the pamphlet does not have to follow any prescribed pattern. It can be in prose or verse, it can consist largely of maps or statistics or quotations, it can take the form of a story, a fable, a letter, an essay, a dialogue, or a piece of “reportage.” All that is required of it is that it shall be topical, polemical and short.

My favorite poster from Saturday’s rally makes an interesting ideological point about David Silva’s death.

One KMC officer. One security could control David Silva off property. One canine officer couldn’t handle it nor wait for back up. Youngblood says to family: David was going to die anyway. Justice for all.

Then there were other phrases of verse just as polemical, voicing harsh opinions using sarcasm and wit. Some were more right-brained, inflammatory. A woman with a walker spinning a pink umbrella and wearing a cowboy hat at the rally carried a sign that read, “Good ole boys suppress evidence together.”

Others signs carried these phrases:

Test the police for rabies.

No more stolen lives.

Nine officers plus intoxicated man equals death.

Don’t call 9-1-1 in Kern County or you may get someone killed.

Film the police.

Others offered a more left-brain approach with sensible propositions.

Catch the criminal. Don’t be the criminal.

Bailyn adds that pamphlets were aimed at quickly shifting targets, “suddenly developing problems, unanticipated arguments and swiftly rising, controversial figures. The best of the writing that appeared in this form, consequently, had a rare combination of spontaneity and solidity, of dash and detail, of casualness and care.”

Ideas from the Silva rally that offered such casualness and care read:

We’re not anti-police. We’re anti police brutality.

We are the voice of David Silva.

The world is watching.

Yet, with all the protest signs, I can’t help but think back to Bailyn, and how he wrote that the Revolution also occurred because British ideological currents generated fears across America and how those Americans responded because of the p

olitical gangsters upholding British law. He said the people could see that British officials were self-serving adventurers—degrading and uncontrollable politicians.

The question of whether the Kern County Sheriff is worthy of such protest as a target of poster board signs and political cartoons is up to the individual. All politicians end up getting vilified in one way or another, regardless of being degrading, self-serving, uncontrollable or not.

Americans, and maybe people in general, get violent because we react out of fear on every level. The Silva family, I am guessing, are probably terrified for what happened to David. So their protest could be thought of as a way to fight back against their own fears.

On the other hand, if a sheriff’s deputy reacted out of fear to a rigid-standing David Silva on a midnight street corner, then how can we blame the officer for reacting violently by sicking his attack dog on an unarmed man? What would you do? Would you conquer your fear and try talking to David, offer a knee-jerk attack response, or otherwise?

What do we do when we’re afraid? Sheriff Donny Youngblood used the phrase “heat of the battle” when describing law officers engaging in baton strikes. Aren’t all soldiers in battle afraid? I offer empathy to the officers, while also calling for further analysis of David’s death. The Dolores Huerta Foundation’s idea of a citizen review board is not a bad idea.

In church on Sunday, I socked my punk teenage nephew in the chest because he was choking me from behind in church. Yes, I socked him in church. Dumb. I reacted angrily because I spent four months of the past year bedridden. When I could walk, I spent most of my recovery with the assistance of a cane, on pain meds that didn’t help, and was scared this kid was going to send me back to the hospital.

So I slugged him. Though not hard, I swear.

My reaction —like the officer’s— doesn’t ring correct in today’s society except to those who want to accept our excuses for behaving the way we sometimes do out of fear. I was afraid I was going to get hurt. I reacted violently and wrongly. Did the officer? Yes and yes. Did my nephew apologize? Sure. Did I? Kind of. And how much longer will I make the excuse that my behavior was justified? That ended while writing this article.

Bailyn, who is now ninety years old, wrote nearly twenty-five years ago, “I do not believe that ideas move history; people do, and people are the products of their time and place.”

All of the parties involved can enact change if they want to. But it will take more rallies. More words. More polemics.

“You see, I’m strong,” David’s mother told me just before the rally, right after the public information officer of the sheriff’s department came out of a guard house to tell the Silva family to protest outside of areas cordoned off by caution tape. “I wanted him to see my eyes.”

She said it three more times. Almost as if she needed to remind herself. “You’ll see. I’m a strong woman.”

I wonder what was in those eyes? Fear? Anger? Uncertainty? All of the above? Or maybe just love for her son and the willingness to help instill change.

My final thoughts are words from an anonymous friend in the U.S. government. That friend read my two previous articles on the death of Silva and was saddened. While the conversation was short, that didn’t matter. Like a phrase on a poster board I was told, “These things need to have attention by protest and publicity.”

***