In this Wednesday February 26, 2020 photo, Yarelis Gutiérrez Barrios holds up a cell phone photo at her home in Tampa, Fla., of herself with her partner Roylan Hernández Díaz, a Cuban asylum seeker who hanged himself in a Louisiana prison. An Associated Press investigation into Hernández Díaz’s death last October found neglect and apparent violations of government policies by jailers under U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. (AP Photo/Chris O’Meara)

By NOMAAN MERCHANT, Associated Press

Roylan Hernández Díaz’s long journey ended inside a white-walled cell in the solitary confinement wing of a Louisiana prison.

Nearby were the last of his belongings: a tube of toothpaste, a few foam cups, and a sheet of paper explaining how he could request his release from immigration detention. He had already been denied three times.

The Cuban man had been placed in solitary six days earlier because he told his jailers he would refuse all meals to protest his detention. The jailers put him there even after medical staff had referred him for mental health treatment three times and documented an intestinal disorder that caused him excruciating pain.

And for at least an hour before he was found to have hanged himself, no one had opened the door to check whether he was alive.

His death might have been prevented. An Associated Press investigation into Hernández Díaz’s death last October found neglect and apparent violations of government policies by jailers under U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, at a time when detention of migrants has reached record levels and new questions have arisen about the U.S. government’s treatment of people seeking refuge.

ICE requires migrants detained in solitary confinement to be visually observed every 30 minutes. Surveillance video shows a jail guard walking past Hernandez’s cell twice in the hour before he was found, writing in a binder stored on the wall next to his cell door. She doesn’t lift the flap over the cell door window or try to look inside. The last person to look in the window was an unidentified jail employee, 40 minutes before Hernandez was found.

A person who works at the jail and spoke to the AP on condition of anonymity says the jail later discovered Hernández Díaz couldn’t be seen from the window.

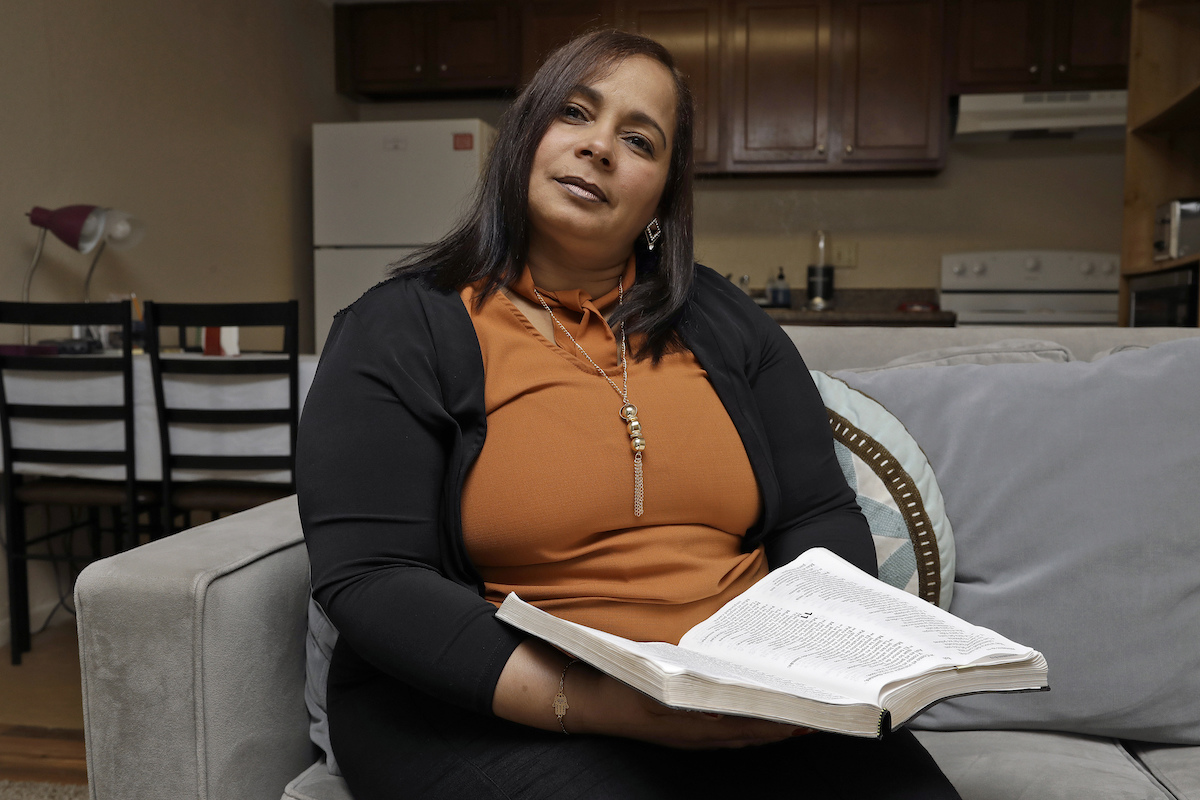

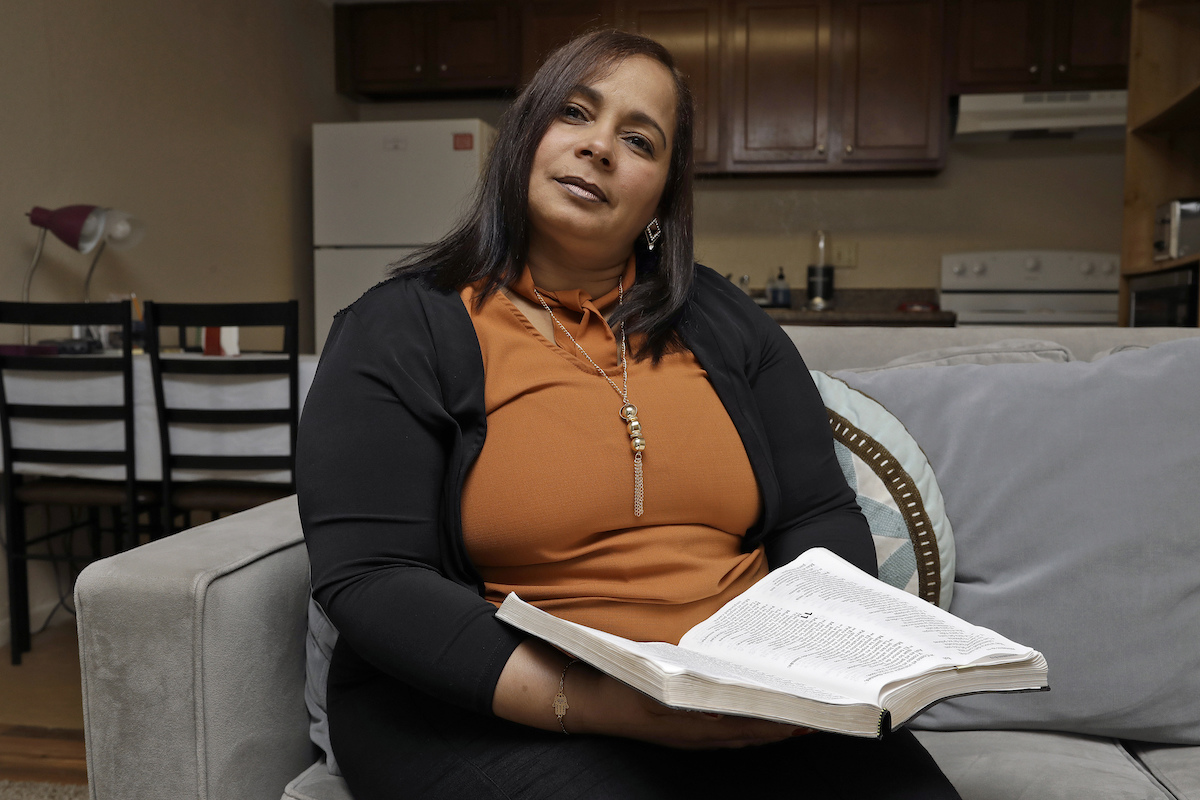

Yarelis Gutiérrez Barrios was Hernández Díaz’s partner. She had been with him for three years as they voyaged through South and Central America, always looking for a way to reach the United States. The man she knew was resilient, she says, determined to win his asylum case, not the kind of man who would give up easily.

“I think they let him die,” she says.

Yarelis Gutiérrez Barrios poses for a photo at her home Wednesday, February 26, 2020, in Tampa, Fla. (AP Photo/Chris O’Meara)

***

Hernández Díaz spent much of his 43 years in rebellion against the Communist government 90 miles from the United States.

In his early years, he had refused to join a youth group. Then he refused compulsory military service and protested the regime of Fidel Castro.

In 1994, when he was 18, he tried to flee the island in a boat with his father and brother. But they were captured and imprisoned.

Hernández Díaz was jailed for about two weeks. When he tried to escape again, in 2001, he was caught and sentenced to nine years in prison. Upon his release, he continued to be denied jobs and harassed by police.

In 2016, he left Cuba for Guyana, a tiny country in South America, because he could travel there without a visa. From Guyana, he set off for the U.S.

Hernández Díaz and Gutiérrez Barrios met in Ecuador in 2016. They were among a group of Cubans camping outside the Mexican embassy in Quito, Ecuador’s capital, to demand visas that would allow them to reach the U.S.-Mexico border and request asylum. Mexico refused to grant the visas and Ecuador moved to deport the protesters to Cuba.

So they fled. They sold juice from a cart in Argentina, then lived for a year in Peru.

In both Argentina and Peru, Gutiérrez Barrios recalls, they struggled to support themselves and were told it would be near-impossible to be allowed to settle permanently.

“In the end, we were going to come to the United States,” she said.

Through Ecuador and Colombia, they reached the jungle connecting South and Central America known as the Darien Gap. The region is roadless and lawless, controlled largely by gangs who prey on the thousands of migrants who try to traverse it each year.

The couple walked several days in light and dark before reaching a village in Panama. They surrendered at a government border checkpoint.

But in the jungle, Gutiérrez Barrios says, Roylan lost the papers he had carried with him from Cuba documenting his imprisonment and political problems—papers that would be key to proving his asylum case in America.

They were detained 10 days in Panama, then taken to a border town in Costa Rica. One by one, they boarded buses and made it through border checkpoints in each country along the way: Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico. They spent several days detained in Mexico.

After five months, on May 18, 2019, they arrived at the border bridge between Juárez, Mexico, and El Paso, Texas. They waited to be allowed inside.

Hernández Díaz requested asylum and was taken into detention.

He and Gutiérrez Barrios were initially taken to the same holding facility near the bridge. Men and women were separated and placed in small, cold cells.

She last saw him from across the dining room a few days after they crossed. It was lunchtime, but they weren’t permitted to speak to each other.

Gutiérrez Barrios was eventually released, but an officer at the facility told her Hernandez had been taken to a detention center in Mississippi.

After a few weeks, he would be transferred to Louisiana, a state that for thousands of migrants has become synonymous with prolonged detention. He remained jailed, though an initial screening found his asylum claim was credible.

***

In the last days of his administration, President Barack Obama revoked a policy known as “wet foot, dry foot” that had given thousands of Cubans a path to permanent residency in the U.S. and, eventually, to citizenship.

Under President Donald Trump, the U.S has restricted the grounds on which people can request asylum and pushed immigration court judges to process and deny asylum claims more quickly. It has also detained thousands of asylum seekers who previously might have been allowed to live and work in the U.S. while their cases were pending.

Those policy changes occurred after Hernández Díaz left Cuba for the last time, but they shaped the last months of his life.

Last June 13, Hernández Díaz arrived at the Richwood Correctional Center. Located in Monroe, in the northeastern part of the state, Richwood is one of at least eight Louisiana prisons that converted into immigration detention centers during the Trump administration.

Looking to fill prisons emptied by criminal justice reform, rural Louisiana communities filled jail beds with asylum seekers and other migrants. At one point last year, Louisiana had about 8,000 migrants in detention, second only to Texas and up from about 2,000 migrants at the end of the Obama administration.

Louisiana also has become notorious for the broad denial of parole to migrants, particularly large populations of Cubans, Venezuelans, and people from South Asia. A federal judge in September ruled that ICE’s New Orleans field office was violating the agency’s own guidelines by failing to give each migrant a case-by-case determination of whether they could be released.

Little changed immediately after that ruling, but there has been some improvement since. According to the American Civil Liberties Union of Louisiana, of 345 requests between October 17 and December 10, just four were granted. ICE granted parole to approximately 20 percent of asylum seekers in January and February, the ACLU of Louisiana said, citing data ICE has provided in the federal lawsuit.

ICE spokesman Bryan Cox declined to comment on parole practices in the state but said that “any suggestion that the majority of persons arrested by ICE are detained is false.”

The detainees at Richwood and other detention centers have repeatedly protested.

At one Louisiana jail, men from South Asia have staged a hunger strike lasting 100 days and counting. At another, officials pepper sprayed migrants who participated in a sit-in to demand freedom.

Wrote one Richwood inmate last year, in a letter released by the advocacy group Freedom for Immigrants: “We only want our liberty to pursue our cases freely and to leave this hell, because Louisiana is a cemetery of living men.”

***

Speaking by phone from Havana, a man who was detained at Richwood recalls a time he saw Hernández Díaz standing in the yard.

Hernández Díaz was doubled over and clutching his stomach. His face was pallid. He had accidentally eaten something with sugar in it, which had aggravated his condition.

According to the now-deported detainee, Dariel Hevia León, Hernández Díaz constantly complained of the pain and felt medical staff was not treating him properly.

“He told me that ‘the jail was killing me,'” Hevia said.

According to an ICE report compiled after his death, Hernandez was seen by medical staff when he arrived at Richwood and confirmed to have irritable bowel syndrome.

Yarelis Gutiérrez says he had been diagnosed with intestinal problems in Peru and had needed medical help in Panama and Mexico during their journey.

People with IBS can control their pain with medication and diet. The syndrome also has been associated with anxiety and depression.

When Hernández Díaz arrived at Richwood, he refused a mental health referral, the ICE report says. He would twice be referred for mental health treatment, in August and September, though the report doesn’t say why. It says he refused both times.

Hernández Díaz told Gutiérrez Barrios, his partner, and detainees at Richwood that he would fight his immigration court case until the end. But according to what Hernandez told others later, he faced a huge, perhaps insurmountable challenge: the loss of much of the paperwork documenting his case in the jungle.

Yarelis Gutiérrez Barrios holds up a cell phone photo of her partner Roylan Hernandez Diaz and herself Wednesday, February 26, 2020, at her home in Tampa, Fla. (AP Photo/Chris O’Meara)

He made his first immigration court appearance from Richwood, speaking to a judge in New York over video.

The Executive Office for Immigration Review declined to release its recording of that hearing. According to his partner, the judge told him he needed some evidence to prove his case. So Gutiérrez Barrios started calling people in Cuba and Cubans who had left the island, asking them to write letters supporting his claim that he was persecuted.

“I barely got him three letters, because it took me quite a while to get them since the people in Cuba are afraid to talk,” she said. “They are afraid to get involved in problems of this magnitude, but I got them.”

On October 9, he had what would be his last court hearing. According to a recording, the judge told Hernandez his final hearing would be scheduled for January 30, more than three months away. Hernández Díaz responds by saying he doesn’t understand.

“My case is my case. I’ve already sent my evidence,” Hernández Díaz said, according to a translator heard on the recording. “I’ve been detained here. My rights have been violated. I don’t have any benefits. I’ve already sent three letters, and my wife is out in the street.”

The judge repeated that his final hearing was January 30 and said he could have a lawyer present if he wanted. As the translator explains to Hernández Díaz , the judge says, “Have a good day.” The recording ends.

According to Gutiérrez Barrios, Hernández Díaz called her afterward to tell her that he was going to mount another hunger strike.

“I told him, ‘Don’t do it,’ because I was afraid for his health, that he wasn’t going to endure it,” she says. “He got mad at me. He tells me, ‘I’m going to do it. Support me, because it’s the only way I have to get out of here.’ In his mind, that was the only way.”

The next day, October 10, the ICE report says he was given a medical evaluation before being taken to segregation for threatening a hunger strike. A nurse found his physical and mental health to be normal “except for a withdrawn emotional state.”

***

The interior of the cell where Hernández Díaz was held when he died did not have video surveillance, according to the Ouachita Parish Sheriff’s Office, the local law enforcement agency called to investigate soon after he was found dead.

But the sheriff’s office obtained video from the hallway outside his cell that captures the last hour before his body was found. This is what it shows:

- 1:19 p.m.: A guard walks up to Hernández Díaz’s door. She takes a binder from the wall next to the door, writes in it, then puts the binder back on the wall. She never looks into the window of Hernandez’s cell door.

- 1:26: A man in street clothes walking by the cell stops to open the flap over the cell door window and looks inside. The sheriff’s office says the man was a jail employee but doesn’t have his name in its records.

- 1:54: The guard comes back. Again, she takes the binder, writes in it, and puts the binder back without looking into the cell.

- 2:04: Three staff members and what appears to be a jail trusty walk past the cell, filling most of the hallway. Going around the small crowd, a jail captain walks closer to the wall and comes next to Hernández Díaz’s cell door. The captain, identified by the sheriff’s office as Gerald Hardwell, later told investigators he had noticed a “strong odor” emanating from the cell.

Hardwell stops walking and lifts the flap on Hernández Díaz’s door, just as the man in street clothes did. He starts rapping the door with his left hand. He later told the sheriff’s office he couldn’t see Hernandez.

A minute later, he comes back with a set of keys. He uses his left hand to lift the door flap and the right hand to unlock the door, pressing it open.

Hardwell tips his head into the cell, then immediately runs away from the cell, his left hand covering his mouth.

He had discovered that Hernández Díaz hanged himself with a bed sheet tied to the post of his bunk bed.

***

The Ouachita Parish coroner recorded his time of death at 2:15 p.m. —10 minutes after he was apparently dead to Hardwell and others at the jail— and said he was last seen at 1:50 p.m., deputy coroner Joy Davis told AP. The video shows that medical staff stood outside his cell long after he was discovered and that his body was not removed from the cell until almost 4 p.m.

Photos taken of his body show that Hernández Díaz may have been dead for several hours before he was found, based on how the blood had pooled in his hands, according to an analysis done at AP’s request by Dr. Nizam Peerwani, the medical examiner for Fort Worth, Texas, and a forensic expert with the advocacy group Physicians for Human Rights.

Peerwani found that the jail missed several warning signs, indications that Hernandez deserved more attention: a well-documented history of intestinal problems, his repeated refusals to receive mental health treatment, and the hunger strikes he staged. Peerwani says Hernandez’s death is not due to “commission of a violent act perpetrated against him but rather due to omission.”

There is the question of whether he should have remained in segregation at all. According to ICE Health Service Corps guidelines, within 72 hours of when he was placed in segregation for threatening a hunger strike, a health care provider should have reviewed whether to keep Hernández Díaz there. That 72-hour check should have occurred no later than October 13.

There’s no reference to any check occurring in the ICE detainee death report. ICE’s report says that on the day of his death and the four leading up to it, a nurse noted that Hernández Díaz appeared normal or not in distress.

And under ICE’s Performance Based National Detention Standards, anyone in segregation should be monitored at least every 30 minutes.

The video released by the sheriff only includes the hour before Hernández Díaz was found dead, so it’s impossible to determine how many times he had been observed.

The employee at the jail who spoke to AP on the condition of anonymity says Hernández Díaz hanged himself in a corner of the cell that couldn’t be seen from the cell door window. The same employee said it was also common knowledge that guards falsely logged checks they were supposed to make.

ICE and LaSalle Corrections, the private company that runs the jail, declined to confirm whether the guard who appeared outside Hernández Díaz’s cell was fired or whether any other employees were held responsible.

ICE and LaSalle did not answer most questions for this story.

Scott Sutterfield, a development executive for LaSalle, declined to answer any questions “due to pending litigation.” Sutterfield joined LaSalle last year after serving as ICE’s acting field office director for enforcement and removal in New Orleans; he denied one of Hernández Díaz’s requests to be released.

“I can say that LaSalle Corrections is firmly committed to the health and welfare of all those in our custody,” Sutterfield said.

“We cannot speak for an agency contractor,” said ICE spokesman Cox in an email. He added that ICE “holds its personnel, including contractors, to the highest standards of professional and ethical behavior.”

“Further, while any death in custody is unfortunate, fatalities in ICE custody are exceedingly rare and occur at a rate roughly 100 times lower than the national average for persons in federal and state custody nationwide,” Cox said.

Eight people have died in ICE custody since October, the start of the government fiscal year, the same number that had died in the previous year.

At Richwood, a man from Guatemala tried to commit suicide in December while detained in segregation, months after Hernández Díaz’s death.

The man’s attorney, Lorena Perez-McGill, says she had seen him earlier that day and warned the local warden that he might harm himself. Guards were able to stop him from cutting himself 5 minutes after he had started.

Jailers took him to a local hospital where he was given stitches. Then, Perez-McGill says, he was taken back to the same segregation cell.

***

Aside from Gutiérrez Barrios, Hernández Díaz left behind two daughters and a son, as well as his mother and father.

When he left home for the last time, his family knew he hoped to get to America with the intention of making money to support them. Now, they have many questions about his death: How someone so strong in his convictions could have taken his own life? What happened to him in the jail, and why?

“He had struggled to get to this country, because he loved this country, he loved it with all his life,” Gutiérrez Barrios said. “He gave his life for this country.”