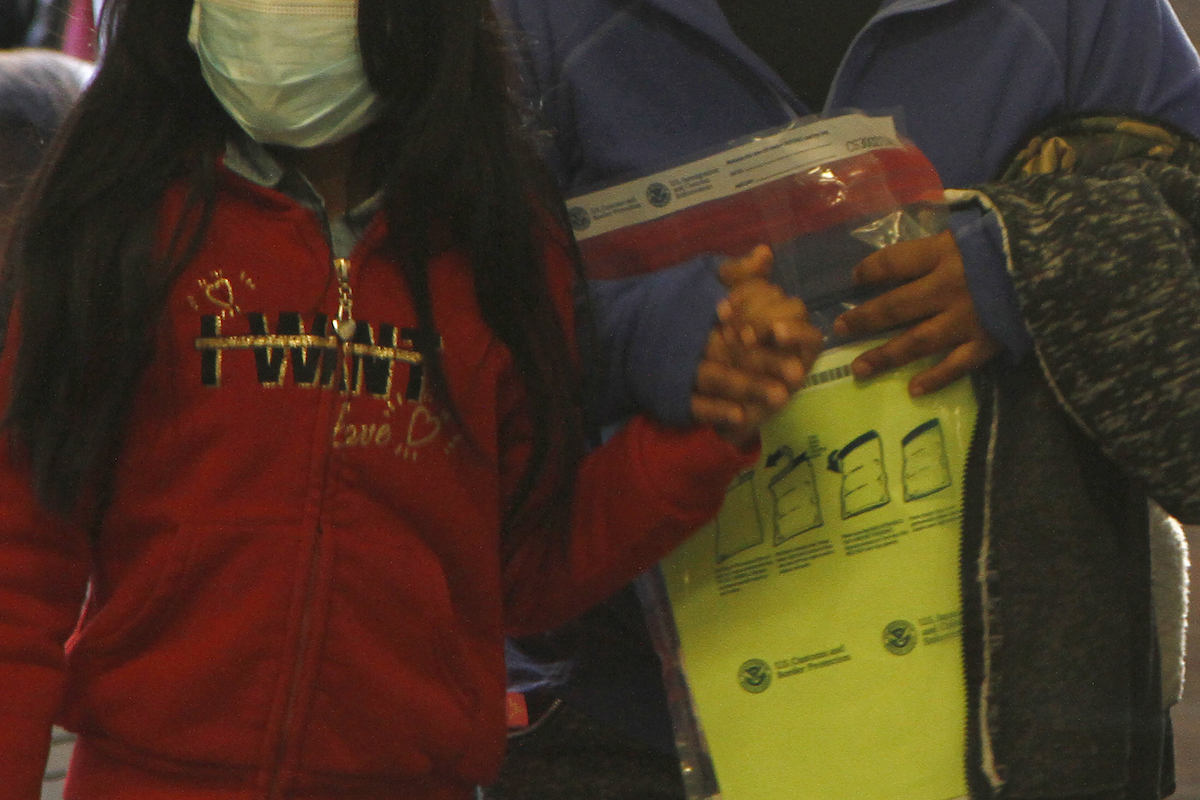

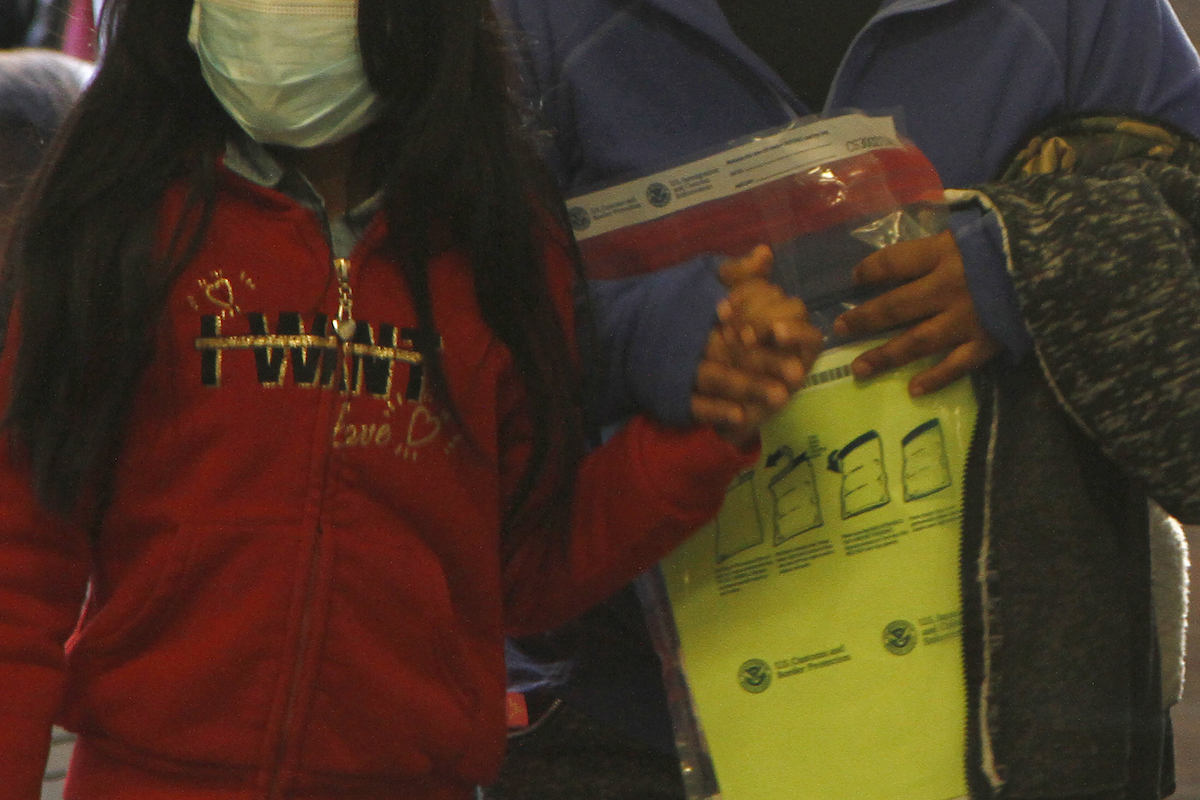

A woman carries a property bag issued by Customs and Border Protection while holding the hand of a girl wearing a mask as they arrive at a mandatory immigration court hearing on Monday, March 16, 2020, in El Paso, Texas. (AP Photo/Cedar Attanasio)

Crises such as the COVID-19 remind us that languages matter when it comes to public health. Not only is making reliable information in multiple languages a question of common sense, for federal agencies, it is also an obligation.

In a head-scratching move, however, the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), the immigration court responsible for immigration cases, temporarily banned judges in federal courts from posting bilingual CDC flyers on how prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus. Only after the public protests by the union of immigration judges (NAIJ) and the coverage in the Miami Herald came out did the EOIR revert its policy.

EOIR has ordered immigration court staff to remove CDC posters designed to slow spread of coronavirus.

No, this is not a parody account.

— Immigration Judges (NAIJ) (@Imm_Judges_NAIJ) March 9, 2020

The initial position of the EOIR, which depends on the executive branch and not on the judiciary, only makes sense in the context of the anti-immigration policies of the current administration and its hostility towards diversity—ethnic, cultural, linguistic or otherwise. It feels like decades ago, but one of the very first actions of the Trump presidency was to axe the Spanish version of the White House website. And while some Spanish-language resources from the federal government are still available, it is an ill omen for what will happen when the coronavirus starts spreading in CBP and ICE detention centers.

Given how chaotic the official response by the Administration and the CDC has been, it is hardly a surprise that the CDC has also fallen short in its multilingual outreach. The English portal for COVID-19 on the CDC website is constantly updated with clearly organized links and resources. Meanwhile, the Spanish and Chinese portals have not been updated in weeks and contain only a fraction of the information and resources in the English version. The information gap between the different versions is considerable.

On March 17, Latino Rebels confirmed that the latest March 16 White House/CDC guidelines are still not available in other languages, proving again that the pattern is continuing.

To be fair, the problem of public health and languages is systemic and goes beyond the CDC and COVID-19. Our health care system is ill equipped to care for a multilingual population, from the training of health professionals to the investment in language services in hospitals and clinics. There is plenty of evidence that along with income, ethnicity or immigration status, with which it often intersects, language is a key factor in unequal access to health care and quality of treatment.

Elderly patients with limited English proficiency, for instance, face more difficulties getting tested for dementia or getting enrolled in clinical trials because of the lack of medical interpreters. In some areas, Latino patients are at higher risk of relapse in their opioid addiction because of insufficient outreach and few bilingual options for treatment rehab facilities. When there is no interpreting available in hospitals and clinics, the task falls on relatives, who are not emotionally or professionally equipped to simultaneously process and relay information for their relatives.

Why do language services matter to prevent the spread of COVID-19? For one, the language rights of individuals with limited English proficiency are protected by the Title VI of the Civil Rights Act (1964) and Executive Order 13166 (2000). The deaths of 7-year-old Jakelin Caal Maquín and 8-year-old Felipe Gómez Alonzo remind us of the current administration indifference to the deadly consequences of the lack of adequate language services. For another, given the need to slow down COVID-19, it is in everybody’s interest that as many people as possible receive reliable and accessible information about preventing its spread.

As the COVID-19 crisis intersects with immigration policy and language rights, it has become difficult to separate incompetence from nefariousness. The CDC’s response, in English or otherwise, suggests an understaffed, overwhelmed organization. However, the EOIR decision to ban bilingual flyers, later reversed, echoes the cruel streak that for writer Adam Serwer characterizes many of Trump’s policies and speeches. What other purpose, other than complying with a minor technicality, could the ban serve, if not to purposely keep that information from immigrants and asylum seekers from Mexico and Central America? As journalist Aura Bogado has noted, what will happen when, given the often-unsanitary conditions in them, there is an outbreak in CBP and ICE detention centers?

Every nook and cranny of the US immigration system seems wholly unprepared yet destined for contagion. I worry that by the time we really hear about it, the explicit and implicit biases against im/migrants will automatically cast those affected as disposable.

— Aura Bogado (@aurabogado) March 10, 2020

Let us not even entertain as a counterargument the idea that if people want information about the coronavirus they should bother learning English. Nobody should get to decide that the lives non-English speakers are less valuable. Of course, one could argue, less immorally, that crises like this show that it is both more economical and more practical if we all share communications in just one language. But how efficient is a system that leaves so many people out? Are the immediate savings in language services worth the human cost, not to mention the cost of testing and treating what could have been preventable contagions? Why skimp on doing the right thing?

The reality is that, no matter how stubbornly we stomp our feet and declare ourselves monolingual, the United States is a multilingual society, and it is harmful to so many to go on ignoring this fact. Language access is not a trivial thing or a liberal piety. It is, in medical situations, often a matter of life and death for particularly vulnerable populations. If anything, what we need is a public acknowledgment of the civic value of speaking, learning, teaching and using languages. It is up to those of us who care about languages, in whatever capacity, to stand up for the value of languages in the public interest, even and specially in times of crisis.

***

Roberto Rey Agudo (@robertoreyagudo) is the language program director of the department of Spanish and Portuguese at Dartmouth College and was a 2018 Public Voices fellow with the OpEd Project.

[…] latest COVID-19 guidelines only available in English. Until late in March, the CDC portal only had partial, outdated information in Spanish and Chinese, initially, to which Vietnamese or Korean, first, and […]