Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele (AP Photo/Salvador Meléndez)

“Fake news,” or disinformation, feels like a new phenomenon but it has existed for as long as politics and government itself. In 2019, on the tail end of Trump’s presidency, and the beginning of another general election in the UK, The Guardian briefly outlined the history of misinformation and the collection of phrases that also surround the hot button term, “fake news.” A point they made sure to mention was that “the online world too, is a fertile breeding ground for zombie ideas.” Those of us who paid attention to the ex-U.S. president’s habitual spouts of uncorroborated statements for the past few years on Twitter will be able to recognize a similar pattern emerging in El Salvador surrounding Nayib Bukele’s presidency.

The Salvadoran journalism community has expressed deep concerns over Bukele using his newfound authoritarian power to suppress the free press and disparage news sources that criticize him. Latino Rebels posted an editorial published by El Faro responding to the president’s latest accusation of tax evasion. In the press release, they shared examples of ways Bukele and the government have denied El Faro access to public information and their attempts to disparage its reputation.

Before this accusation, the young president had also posted comments on Twitter targeting publications and reporters. The best example is his response to a tweet from Mariana Belloso where she pointed out a fact about the president’s security plan that would potentially reduce gang crime. The tweet was a simple statement based on a conference the Bukele had on the radio. However, after the president responded to her tweet, Belloso was the target of violent comments that followed from ardent fans of Bukele. The growing concern is that Bukele exhibits a lack of interest in stamping out the threats of violence against journalists.

Una verdad contada a medias es peor que mil mentiras.

Dije que a medida que la población fuera sintiendo confianza en el plan, que a medida que vieran que la Policía y el Ejército llegaron para quedarse, que a medida pasara el tiempo, dejaran de pagar la renta… https://t.co/H38d5EylRV

— Nayib Bukele ?? (@nayibbukele) July 1, 2019

Beyond the political and institutional battle for transparency in media, there is also the problem of misinformation on the internet. Due to the rise of technology and internet culture, there is a growing community of Salvadoran commenters on YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter, all of whom vary in age and opinions. Of those commenters, few have evidence to support their claims. Similar to the U.S. during the years of the Trump Administration, there is growing disinformation online around political discourse and international affairs.

One such example is this thread on Twitter where the author baselessly accuses Bukele and his family of money laundering through establishing mosques in El Salvador.

#ULTIMAHORA La estupidez de Nayib sobrepasa los limites, critica las ONG's pero no habla de los millones q reciben de grupos radicales de Qatar para las mezquitas fantasmas de los Bukele y q son administradas x su hno Emerson como fachada para LAVAR DINERO.#MafiaBukele pic.twitter.com/ZVBT4zXg8J

— Compatriota Ad Honorem (@CompatriotaESV) May 22, 2021

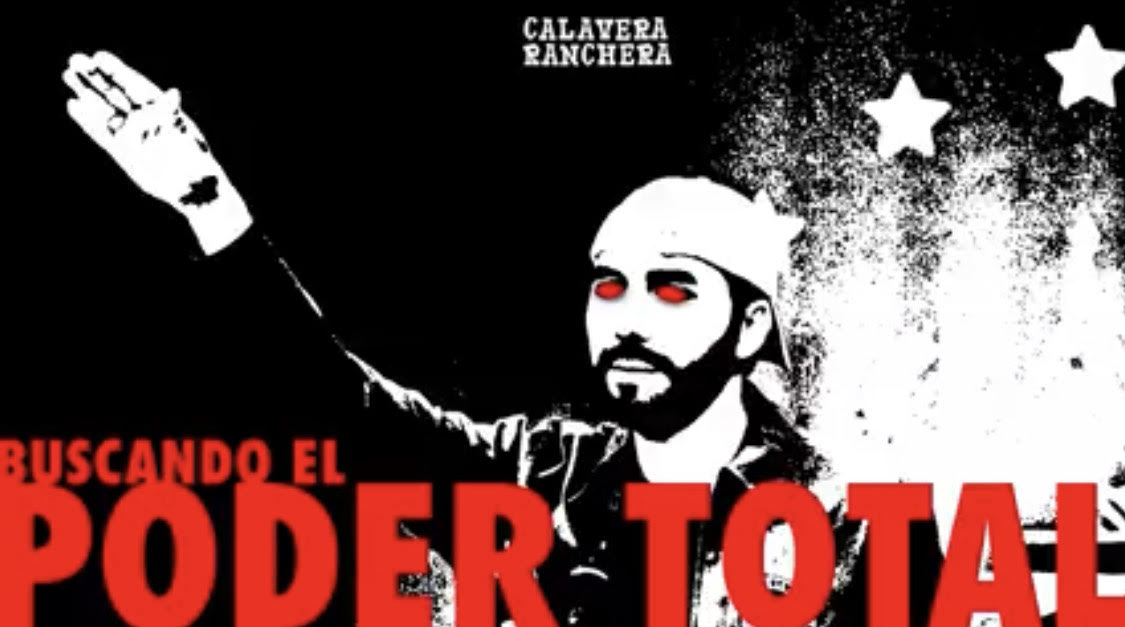

Another similar YouTube video, with a thumbnail titled “Buscando El Poder Total,” which loosely translates to “Looking For Total Power,”, shows a distorted photo of the president, with his signature backward cap, red eyes, and his hand raised in a Seig Heil salute. The video is narrated by a bot and opens by expressing Bukele’s election win as “the worst thing that could have happened.” These kinds of posts spread are often solely based on opinion and those uncorroborated statements provoke fear in a generation that is still traumatized by the violence of the Civil War.

It’s impossible to discuss misinformation, politics, and journalism without referring to El Salvador’s Civil War. The 2019 election represented a beacon of hope and a fear of history repeating itself. Older generations that survived the war and human rights groups worry that Bukele’s authoritarian governing style and habitual use of military force is reminiscent of pre-war days where military intimidation and violence reigned. Bukele has previously downgraded the importance of the 1992 peace accords that ended the war, further concerning those groups who say that Bukele’s majority control of government will deteriorate the democratic policies set in place after the peace accord which included rules to keep the military out of office.

Younger generations, who don’t carry the same battle wounds as their parents, are crippled by gang violence and lack of employment opportunity, and lack of upward economic mobility. This frustration and need for change is what thrust Bukele into the presidency but is also what has contributed to a generational conflict that lives within the private homes of millions of families in El Salvador, and on the internet where it is shared amongst El Salvadoran communities around the globe.

So what news sources can be considered trustworthy and transparent? There is a myriad of opinions on Bukele and New Ideas that span across the internet and Latin America. The traditional and heavily biased news publications like El Diario De Hoy, La Prensa Gráfica, El Mundo, and El Salvador.com dole out the latest and most relevant news but much like American publications, they all have their political leanings. Some are even funded by political parties themselves. Those publications are also heavily followed by the older generation.

Then there are the millennials who played a large role in the 2019 elections that got Bukele elected into office. They prefer to read publications like El Faro, Factum, Rectum, and reporting from the University of Central America. The way these two demographics consume media speaks volumes about their political views.

These days my father often howls, “¡El país se va convertir a socialismo!” and that Bukele is going to turn El Salvador into an oppressive socialist government such as those seen in Venezuela and Cuba. He, like many other El Salvadoran migrants and generational counterparts, fled the country during the civil war in 1980. The wounds from that conflict remain open and the fears of a return to the military dictatorship of the past live at the forefront of their memory. Despite the complexity of the already fragile El Salvadoran democracy, the generational rift amongst the community, along with the valid concerns expressed by journalists and the free press, it seems the best option we have at this moment is to remain vigilant and see if President Bukele will follow through on his promises made to the people of El Salvador.

***

Rosy Alvarez is a writer and digital media professional based in New York City. She is a contributing writer for VUE NJ magazine and is self-published. A writer by day and tv junkie by night, Rosy is a lover of stories who is always on the hunt for the next escape. Twitter: @aroseinbklyn.