Originally published in Pa’lante Latino on September 23, 2011

We live in a time where revolutionary sentiments unite people under one cause to help them topple dictatorships, sanguine regimes and challenge government policies. It is no surprise that such outcry is spreading around the world. From Egypt to Libya to Wall Street, people have become aware about the power of collective demonstrations. When demands are not met, an uprising is bound to occur and the events that follow will change the status quo.

Such was the case on a fateful September 23rd, 1868 in Lares, Puerto Rico. That historic revolution is better known as El Grito De Lares.

On plans designed by Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances and Segundo Ruíz Belvis, nearly 1000 rebels gathered on September 23, 1868 in the hacienda of Manuel Rojas, located in the vicinity of Pezuela, on the outskirts of the town of Lares, in the midwest region of Puerto Rico.

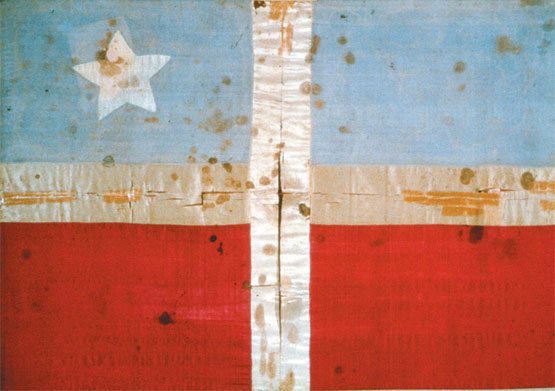

Poorly trained and armed, the rebels reached the town by horse and foot around midnight. They confiscated local stores and offices owned by “peninsulares” (Spanish-born men) and took over the city hall. Spanish merchants and local government authorities, considered by the rebels to be enemies of the fatherland, were taken as prisoners. The revolutionaries then entered the town’s church and placed the revolutionary flag (the Lares flag), knitted by Mariana Bracetti, on the High Altar as a sign that the revolution had began and the Republic of Puerto Rico was proclaimed under the presidency of Francisco Ramirez Medina. Many of the Puerto Rican rebels were African slaves who had escaped and in hiding. Others were middle and upper class creole that were motivated by the idea of freedom to develop economic opportunities without the restrictions of a foreign feudal power. All slaves who had joined the movement were declared free citizens. The revolt would be known as El Grito de Lares.

Spanish forces eventually ended the insurrection when the rebels attempted to take the next town, San Sebastian del Pepino. Even though the revolt in itself failed, its overall outcome was positive, since Spain granted more political autonomy to the island.

On this day, we honor those who sacrificed their lives for believing in freedom. Although these brave souls knew the odds were against them, they still plowed ahead. For them the only way was forward for their bloodstream was impregnated by the heroism and willingness to die for what they believed in.

In honor of their legacy, to their souls, we proudly “gritamos” Pa’lante y Viva La Revolución.

http://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/bras.html

http://nylatinojournal.com/home/history/americas/el_grito_de_lares.html

[…] we would go to the town of Laras in the coffee-growing region, to celebrate the anniversary of the Grito De Laras rebellion. People would crowd under the overhangs of storefronts so they wouldn’t bake in the sun as one […]