On the eve of World War II, the Nazis began to describe the European Jews as “Untermenschen.” The word literally means “subhumans”—a creature that resembles a person, but is nevertheless a bestial humanoid aberration.

This was a way to dehumanize them in preparation for a statewide programm of mass extermination. Since the Holocaust, scholars have recognized the process of dehumanization as a central part of genocidal campaigns, one that erases the moral dilemmas normally associated with hurting others by sanding down innate empathic capacities.

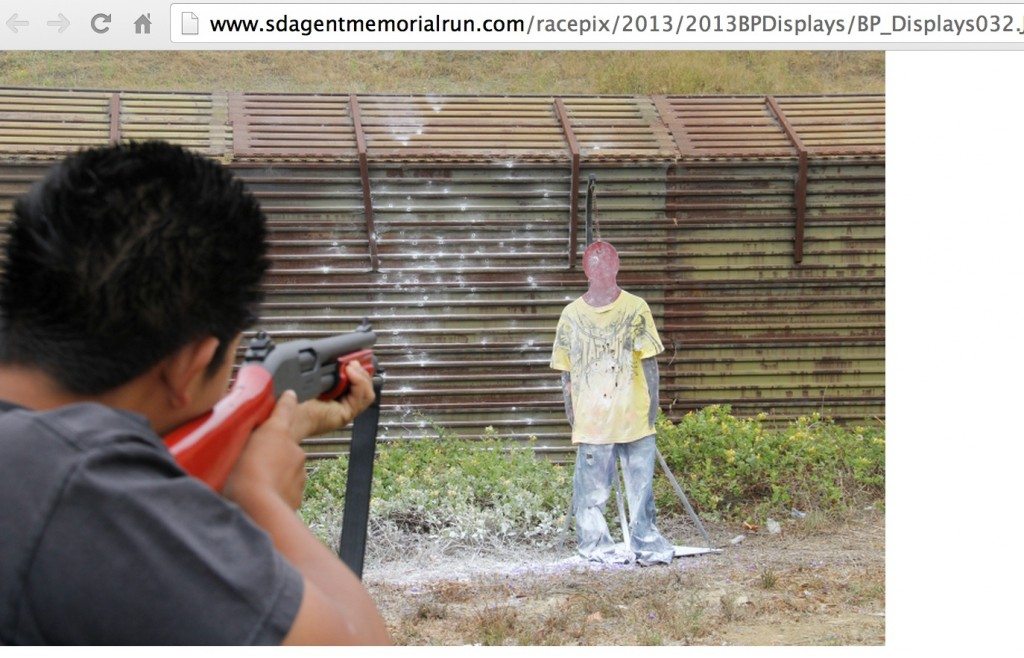

In any campaign of hatred, dehumanization is not the final endpoint; rather, it is a milestone that must be reached in order to enable a desired degree of violence. Dehumanization doesn’t always end in ethnic cleansing. It can take other forms, which, while they may be less extreme, are equally sordid, like teaching children how to shoot at effigies of people who are different from them.

At a community event to honor fallen agents in San Diego last year, the local Customs and Border Patrol outfit facilitated an activity in which children were given less-than-lethal rifles and shotguns and instructed by agents on how to fire at cut-out targets resembling adolescent migrants. One of the targets is even wearing a “Tapout” t-shirt, a common article of clothing donned by young people on either side of the border. In one of the images, a youth seems to be aiming his gun at the target’s head.

For its part, CBP San Diego absurdly justified the event as a part of a community-wide expo meant to “build relationships and increase awareness about law enforcement.” The agency has reportedly claimed that they will continue to host the event in the future, but will use neutral targets to assuage public outrage.

It’s bad enough that the CBP fails to connect the dots between its showy display of mock violence and the renewed controversy in the media over its agents’ slaying of migrants. But even worse, the fact that CBP defended the activity as a community-building event indicates they see an aggressive disdain for migrants as a way to strengthen communal bonds. United in dehumanization we stand.

Activist Pedro Ríos of the American Friends Service Committee said that the incident is indicative of how border communities have become areas of low intensity conflict, where the specter of violence is something expected and even sanctioned. “When violence becomes normalized to the extent that civil society stops questioning it, you stop seeing how wrong it is,” he said. He mentions how the Border Patrol in San Diego possess a coveted space as leaders in the community, even visiting elementary schools to hand out good citizenship awards. “Could be that one day, a Border Patrol agent gives out a [citizenship] certificate to a kid, while next day he might be involved in a beating?”

Since 2004, the number of Border Patrol agents has doubled, and with such a rapid expansion the quality of recruits has suffered. Agents with less training are more likely to employ crude means of handling people they view as problematic. At least twenty unarmed have been shot and killed along the border by the Border Patrol since 2010, some of them in the back. None of the agents implicated in the murders have faced any form of retribution.

Green shirts are even allowed to fire on migrants who throw rocks at them, whereas such excessive retaliation would be completely reprehensible if committed by a domestic law enforcement group. There is a reason for this discrepancy: Migrants are viewed as less than human. Instead, they are imagined as desperate, free-moving hordes infiltrating from a strange land, shouting and chattering in foreign tongues; subhumans, Untermenschen.

Agents operate in a broader society that automatically presumes the criminality of undocumented people. Their most doltish opponents freely call them “aliens,” but even mainstream sources describe them with the slippery term “illegal.” As if all of that didn’t make it difficult enough to attain value in the eyes of society, undocumented people are mostly relegated to bottom rung jobs with low pay and respectability. Although Americans value hard work, we don’t necessarily value the work of the lower class. We are a nation of aspirers, holding up the livelihoods of the super rich as ideals for which to strive, while giving little consideration—let alone respect—to the men and women who package our food and stich together our clothes.

The subhuman characterization of undocumented people becomes even more dangerous as the prospect of a hyper-militarized border grows inevitable. The immigration bill sitting in Congress would nearly double the number of border patrol agents to 40,000—the size of Serbia’s entire army—and create “the most militarized border since the fall of the Berlin Wall,” as Senator John McCain boasted last year. Even if the bill doesn’t end up passing, defense and surveillance corporations have such a vested interest in a dumping their war technology from overseas onto the southern border that any future iteration of the bill will likely look much the same.

It’s in the context of enhanced militarization and an already dehumanized perception of Latin American migrants that the San Diego’s obtuseness about their “community event” is so worrisome. It doesn’t matter their intention; history has shown, again and again, what happens when you simultaneously strip a person of their humanity and promote fatalistic solutions to social problems.

It’s unfortunate that any armed, aggressive agency can rise to such prominent civic stature in a community; but at the very least, the Border Patrol in San Diego and everywhere else could avoid teaching children how to violently dispense with people who are different from them.

Even that might be too much to ask for. Just last week, another unarmed migrant was shot dead across the border from San Diego.

***

Aaron Cantú is a Brooklyn-based journalist @alternet @truthout @thenation. A “revolutionary generalist” who focuses mostly on drug law, criminal justice, and [misc], you can follow Aaron on Twitter @aaronmiguel_ or visit his site: aaronmiguel.com.

[…] Read more of this article by Aaron Cantú for Latino Rebels here. […]

The Gnostics derived their http://633cash.com/Games leading doctrines and ideas from Plato and Philo, the Zend-avesta, the Kabbalah, and the Sacred books of India and Egypt; and http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” thus introduced http://633cash.com/Daftar into the bosom of Christianity the cosmological and theosophical speculations, which had formed the larger portion of the ancient religions of the Orient, http://www.cintaberita.com joined to those of the Egyptian, Greek, http://633cash.com/Promo and Jewish doctrines, which the Neo-Platonists had equally adopted in the Occident..It is admitted that the cradle http://633cash.com/Deposit of http://633cash.com/Withdraw Gnosticism is probably to be looked for in Syria http://633cash.com/Berita and even in Palestine. Most of its expounders wrote in that corrupted form of the Greek used by the Hellenistic Jews…and there was a striking http://633cash.com/Girl analogy between their doctrines and those of the Judeo-Egyptian Philo of Alexandria; itself the seat of three schools, at once philosophic and religious, the http://633cash.com/LivescoreGreek, the Egyptian, and the Jewish. Pythagoras and Plato, the most mystical of the Grecian philosophers (the latter heir to the doctrines of the former), and who had travelled, the latter in Egypt, and the former in Phoenicia, India, and Persia, also taught the esoteric doctrine…The dominant doctrines of Plutonism were found in Gnosticism