I spent Memorial Day weekend in Tijuana, Mexico doing the same thing I did the weekend before, honoring U.S. military veterans. The sound of that still sounds strange to me, but unfortunately it is what it is. Tijuana is a place I’ve been to many times, but this time it was way different for me than ever before. This time i got to see the real Tijuana, not just the night life scene on La Revolución.

I left from LA in the morning and while cruising through Oceanside and San Diego I got hit by flashbacks as I passed the places I had trained at with my brothers to become U..S Marines. I finally set foot in Tijuana, a place I had only been to party many times as an 18-year-old jarhead. Qué pendejo is all I got to say about that guy. For the first time in my life, I crossed the first border entry I ever crossed, while it was daylight. What I saw this time woke me up.

As much as this trip was a personal journey for me, it really isn’t about me. I had been invited by Hector Barajas of the Deported Veterans Support House (The Bunker), to come down and meet various US military veterans that have been deported and to attend their Memorial Day service.

I passed thru El Bordo, a canal where many of the city’s homeless live in cardboard boxes and whatever else they can find to use as shelter. Many deported veterans and other deportees call El Bordo home.

I grabbed a taxi to Playas, the Mexican beach that is home to Friendship Park and the end of the 640-mile wall that we have along the US-Mexican border. A heavy feeling came over me watching this great wall of separation extend into the Pacific Ocean.

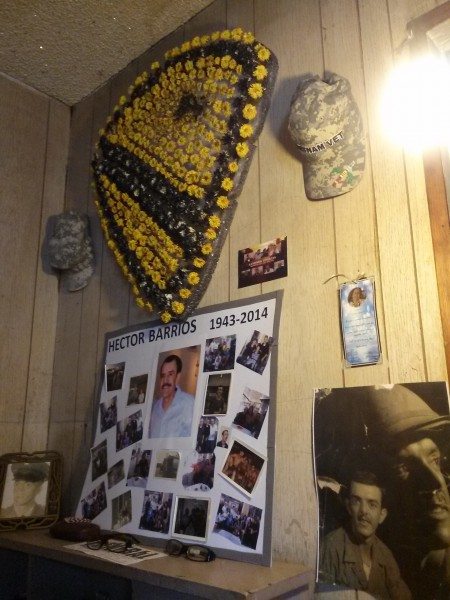

The vets were already set up and getting the event started with their supporters and I quickly realized that this was a joint operation. Joining them in solidarity stood las mamás deportadas from the organization Dreamers Moms, Tijuana with deported moms like Yolanda, María and the countless others whose only dream is to be reunited with their kids and grandkids. As I peered to the other side through the miniature holes, I could see a crowd of family and supporters that had gathered on the US side of the border, el otro lado. The pain was everywhere. Especially real with the memorial of Héctor Barrios, a Vietnam veteran who had passed away last month after being banished from the country that he fought for.

Then the vets began to speak, one by one they told their stories. They spoke of the isolation, the pain and the separation. They spoke of having to learn Spanish after being in the U.S. since age 3 and of the struggles to adjust to life in a country that they don’t know. They spoke of their military brothers and they declared that despite everything that has happened to them, the US is still their home.

Throughout my time in Tijuana, I met veterans that have been deported for various offenses, some as minor as marijuana possession and some for more serious charges. I met deported Navy veteran Alex Murillo, soldiers Ruben Robles, Fernando Orosco and many others from groups like Veterans Without Borders and Border Angels. Then I met a deported Marine, pastor Roberto Salazar. He runs a men’s home to help people get on their feet in Tijuana and hosts Cruising for Jesus events.

The vets I met admit to and own their mistakes, yet their one request is another chance. Estimates put the amount of deported veterans between 3,000 and 30,000—the exact number isn’t known. But being deported never should have happened in the first place. Separating families through deportation doesn’t represent the family values of the U.S. Deporting military veterans doesn’t represent those values either. Why are we letting this happen?

Folks say they shouldn’t have committed the crimes, but they’ve paid their debts in the U.S. prison system and now they pay double or worse by being deported. There’s no appeals system, no medical care, no veterans benefits and no representation. They’ve been banished and their service to the U.S. has been forgotten. If we dig a little deeper, the equation that got most of them there is simple: poor immigrant kids from places like East LA, Compton and inner-city Baltimore get recruited to join the military where violence and alcohol are easy ideals to aspire to, afterwards they’re discharged but they don’t get the help they need to fully deprogram. Throw in PTSD on top of that and it’s a recipe for disaster. Now deported for life, they’ve been left to deal with it all on their own. I think about all of the jails and immigrant detention centers that we have built in recent years. Imagine if we had built veterans rehab centers instead.

Of all the beautiful and heartbreaking artwork on the border wall, one image stands out to me the most. On many of the posts there is the painted name of a deported veteran. We should all be working to make sure that those names are painted over one by one as we bring our veterans home.

Let people know that this is happening. Talk to your friends about it, contact your representatives. As a nation of immigrants, we owe it to our immigrants. As a nation that is always ready to go to war, we also owe it to our veterans.

***

GL is a bilingual hip-hop artist known as GueroLoco. He learned Spanish in the Marines and is currently focused on “Bilingual Nation USA,” a program that encourages students to learn another language through live music presentations and motivation. He is from Indianapolis and currently resides in Los Angeles. You can contact him @gueroloco.

After read a couple of the articles on your website these few days, and I truly like your style of blogging. I tag it to my favorites internet site list and will be checking back soon. Please check out my web site also and let me know what you think.

http://trio4d.com/

http://trio4d.com/promo-bagi-player-trio4d.html

http://trio4d.com/daftar-member.html

http://trio4d.com/cara-bermain-togel.html

http://trio4d.com/informasi-pasaran.html

http://trio4d.com/buku-mimpi.html