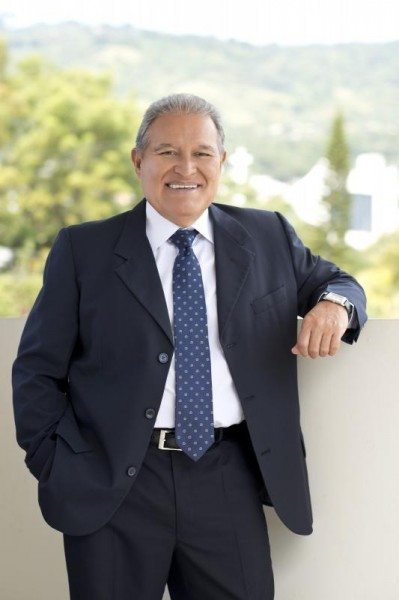

On Sunday, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, who went by the nom de guerre “Comandante Leonel González” during El Salvador’s 12-year civil war, was adorned with the presidential sash as he officially assumed the office of the presidency.

Gripping the sides of the podium with both hands, he addressed the nearly six thousand guests, including 13 foreign leaders, invited to attend the inauguration of the country’s first former guerrilla. “I pay tribute to the sons and daughters of this nation who spilled their blood fighting for justice—especially the farmers, workers, students, syndicalists, intellectuals, artists and professionals, who organized and gave everything for a free homeland.”

The 69-year-old former teacher and leader of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) has promised to boost the Central American republic’s economy by signing onto Petrocaribe, Venezuela’s regional program offering subsidized oil to alliance members.

Cerén has openly stated, however, that he plans to govern less like Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela and more like José Mujica of Uruguay, another former guerrilla turned president.

El Salvador’s new president isn’t the only one enchanted by Mujicismo. Just last month #UnPresidenteDiferente was trending on Twitter among Spaniards wanting to trade in Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy for someone like Mujica, known by fans as the “world’s poorest president” for giving away 90 percent of his salary, living in a modest country home, driving a 1987 VW Beetle and refusing to wear ties, among other things.

Mujica is also the brave mastermind behind Uruguay’s new marijuana law that allows citizens to grow and buy weed for recreational use, in an effort to destroy black markets and address marijuana use as a health issue instead of a criminal one. “In no part of the world has repression of drug consumption brought results,” Mujica explained while the bill worked its way through the General Assembly. “It’s time to try something different.”

And if that weren’t enough, he supports reproductive rights (rare in Catholic Latin America) and environmental protection, and he’s offered to receive detainees from Guantanamo Bay, blasting the United States, “which on the one hand wants to wave the flag of human rights and assumes the right to criticize the whole world, and then has this well of shame.”

The former guerrilla fighter even opposes war, of any kind, telling the students at American University, “I used to think there were just, noble wars, but I don’t think that anymore. Now I think the only solution is negotiations. The worst negotiation is better than the best war, and the only way to insure peace is to cultivate tolerance.”

I have to admit to being a full-blown Mujicista myself.

As I’ve explained in an earlier article, Mujica represents a new leftism for Latin America, one that is committed to the progressive goals shared by the Cuban and Bolivarian revolutions, but which rejects the undemocratic methods employed by Fidelismo and Chavismo. Leaders like Mujica clearly have big plans to move their countries in a new direction (Mujica campaigned for the passage of the marijuana law, even though polls showed a majority of Uruguayans opposed legalization) but, ultimately, leaders like Mujica believe in the sacred sovereignty of the people (after serving only one term, and despite his immense popularity, Mujica will not be running for re-election this year).

President Cerén, who promises to lead with “honor, austerity, efficiency and transparency,” appears to be just such a leader. So does President Michelle Bachelet of Chile. Both have put forth major agendas to place their countries on a more progressive path, and both thus far have pitched their ideas directly to the people, receiving an ocean of enthusiasm in response.

This is the kind of leftism the people of Latin America should demand from now on, in Cuba, Venezuela and elsewhere. This new leftism is not what the Castros have dumped on top of Cuban society, nor is it the leftism the Chavistas have beaten onto Venezuela. It’s also not the neoliberal, anti-revolutionary politics coated with an anti-totalitarian veneer being sold by the likes of Leopoldo López.

More than anything, Presidents Mujica, Bachelet and now Cerén offer a third way to the people of Cuba, Venezuela and other countries who reject Fidelismo and Chavismo, but who know that they don’t want to see their homelands regress into being the right-wing, neoliberal, banana republics of old.

Let’s hope the rest of Latin America gets sprinkled with more Mujica magic.

***

Hector Luis Alamo, Jr. is a Chicago-based writer. You can connect with him @HectorLuisAlamo.