EDITOR’S NOTE: José Ángel N. wrote to Latino Rebels and gave us permission to publish this letter. It has also appeared here and here. You can visit José Ángel at his blog.

July 25, 2014

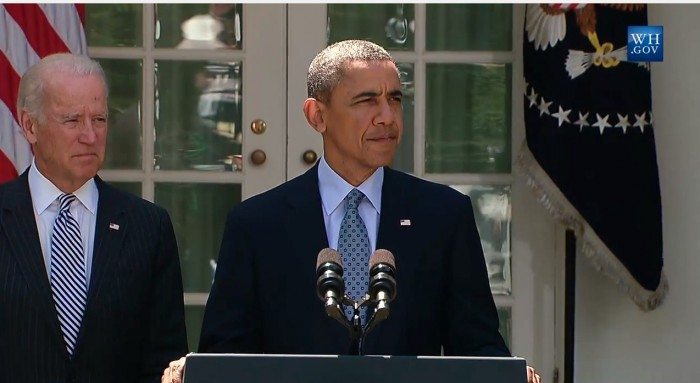

Dear President Obama,

I know you will probably never read this letter. But, as a good Mexican, I’ve been taught to expect disappointment in advance, so there is no harm in trying.

My name is José Ángel N., and I am an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. I have lived in Chicago most of my life, and the night you were elected U.S. President I watched with my face pressed against a chain-link fence as you delivered an impassioned speech at Grant Park.

I come from Guadalajara, a city that you visited during your first official trip to Mexico as President. What did you think of my city, by the way? I have not been home in two long decades, so your memory of it is more current than mine.

Like most people, I came to the United States because I heard that people here had a chance to start over. Actually, I didn’t hear that. The news of the riches of our neighbor to the north reached me in the form of shiny cars, designer clothes, flashy shoes, and impressive electronic gadgets that people in my neighborhood brought back with them when they returned from the United States. My knowledge of America was strictly empirical. That was not, incidentally, a word I knew when I first left Mexico at 19 years of age. I learned it first in English here in Chicago when I was almost 30 years old, during my freshman year in college. And only years later did I learn its Spanish equivalent, empírico, with its ostentatious accent mark on the second syllable, which gives the word a nice rounded sound, like a bubble that first bursts in your mouth and then closes gently.

It was because of that knowledge, because I knew that, in order to afford even a decent, durable pair of shoes I needed to work and save for two months or more, that I decided to leave for the United States. Don’t get me wrong. It is not that I didn’t want to work. I’ve been working since I was 6 or 7 years old. Neither was it the case that my goal in life was to purchase designer clothes. Rather, it was because back then the Mexican economy didn’t compensate fairly for one’s labor, which made one’s hopes for building a better life practically non-existent. This is probably the case even now.

But let me explain myself. My father died at 22, just a few days after I was born, leaving my mother a widow at 16 years of age. I grew up in a crowded one-bedroom house that I shared with 11 family members—my mother, my grandmother, and nine aunts and uncles. Needless to say, poverty defined my life since the day I was born. And thus, because a person from my social background can never hope to satisfy the criteria necessary to obtain an American visa and enter the country through legitimate channels, one night when I was 19 years old, I crossed the border through a dark and filthy sewer tunnel.

Upon arriving in Chicago, I immediately set to work doing all sorts of menial jobs. In addition, I began attending ESL classes where, by mere chance, I learned I could study for something called the GED (the equivalent of a preparatoria diploma, which I would have never dreamed of being able to obtain in my dear México). For a person who had abandoned formal schooling at 13 years of age, the GED test was, I must admit, incredibly difficult, but I managed to finally pass it after three arduous attempts. By the time I started college, I had been in the States for about ten years.

It was in college, President Obama, that I became familiar with American culture and values. I learned, for instance, about the marvelous principle of freedom of speech enshrined in the Constitution. Through my readings, I eventually also learned that a large number of people have gone through great pains to deny this right to many others, that the document of the founding fathers, like the country itself, is a work in process, and that in order to bring it to its full fruition, individuals like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau and W.E.B. DuBois, Noam Chomsky and Cornel West were needed.

It was also in college, President Obama, that I learned about the complexity of words—how ephemeral or powerful they can be, how deceiving or uplifting they sometimes are. And later, many years later, after finishing grad school and after reading American history more closely, it became clear why in this debate over immigration a plurality of voices—some furious, some compassionate, some clueless—usually fills our airwaves and printed and electronic media, but only one is missing, that of the undocumented. Not the Dreamers, who are Americans through and through and speak perfect English, but that of their parents. People like myself, economic migrants who have traditionally not had access to adequate education and who have learned that, in order to survive, one must obey and be silent.

That, in a nutshell, is our story: the story of a minority confined to silence.

All of this is why, Mr. President, I am writing you this letter—to let you know that we are learning your language. Not so we can curse, like Caliban, and return the insult to those that label us “illegals” and deem us lesser human beings. Rather, it is so that we can converse about our mutual problems, sustain civilized discussions, argue passionately perhaps, and reach a common solution.

We could ask questions. For example, how is the case of the 11 million of us currently leading clandestine lives in the U.S. different from that of some of the first Americans going west, following Stephen Austin’s lead to settle in Mexico, “passport or no passport”? Or, would those thousands of children fleeing violence-torn Central America be turned back if they were arriving at Ellis Island from Europe a hundred years ago instead of showing up now at the Mexican border? Or, is this a better country after over two million families have been broken apart? Or, could my three-year old daughter be the next American child to lose her father to deportation?

Just a couple of weeks ago three leaders of the business community came out in support of an immigration reform. They believe immigration should favor foreign capital and talent. Shortly before, Mr. President, you had made the case for a more traditional immigration reform, one that empathizes with working men and women rather than with privilege. This, I believe, is more in line with the everyday reality of the country. Most of us have not come looking for a place to deposit our investment, but for a fertile soil where our frustrated hopes might flourish. Some of us have managed to find relative stability, but at the price of our human dignity.

In my own case, Mr. President, rather than riches, I found your language, your books, your universities. Just like you, in Chicago I found my wife, and it was in this beautiful city that my daughter was born. Chicago gave me a chance to reinvent myself, and now, more than 20 years after arriving here, I still long to call it home.

Toward the end of the summer, President Obama, when you reconvene with your group of advisors on immigration, you’ll have a chance to alleviate the suffering and uncertainty of millions of people who have been contributing to the wellbeing of this country for many years. I hope your advisors offer you powerful enough reasons to take action, and I especially hope that you find the courage to follow your own convictions.

Respectfully,

José Ángel N., author of Illegal: Reflections of an Undocumented Immigrant

♦ ♦ ♦

25 de julio de 2014

Distinguido señor Presidente:

Sé que probablemente usted nunca leerá esta carta. Pero, como buen mexicano, he aprendido a anticipar la desilusión de antemano, así que nada se pierde con intentar.

Mi nombres es José Ángel N., y soy inmigrante indocumentado proveniente de México. He vivido en Chicago la mayor parte de mi vida, y la noche que usted fue electo presidente de Estados Unidos, yo lo escuché, con mi rostro presionado contra un alambrado metálico, pronunciar un emotivo discurso en Grant Park.

Soy originario de Guadalajara, ciudad a la que usted viajó durante su primera visita de Estado a México. Por cierto, ¿qué le pareció mi ciudad natal? Han pasado dos largas décadas desde la última vez que estuve en casa, así que sus recuerdos de mi cuidad son más actuales que los míos.

Como la mayoría de las personas, yo vine a Estados Unidos porque me enteré que aquí la gente tenía la oportunidad de comenzar de nuevo. Bueno, la verdad es que no fue así. Las noticias acerca de las riquezas de nuestro vecino del norte me llegaron en forma de automóviles deslumbrantes, ropa de marca, ostentoso calzado deportivo e impresionantes aparatos eléctricos que las personas de mi vecindario traían con ellos al regresar de Estados Unidos. Mi conocimiento de Estados Unidos fue estrictamente empírico. Por cierto, esa palabra,empirical, no la conocía yo al partir de México a los 19 años de edad. La aprendí primero en inglés, aquí en Chicago, casi a los 30 años, mientras cursaba mi primer año de estudios universitarios. Y sólo años después aprendí su equivalente en español, empírico, con la elegante tilde en la segunda sílaba que le da a la palabra un sonido redondo y agradable, como una burbuja que revienta en la boca y luego la cierra suavemente.

Fue en base a ese conocimiento, el saber que, a fin de poder comprar un par de zapatos decente y duradero había que trabajar y ahorrar hasta dos meses o más, que decidí venirme a Estados Unidos. Pero no me malinterprete. No es que no quisiera trabajar. He estado trabajando desde que tenía seis o siete años de edad. Tampoco se trata de que mi objetivo en la vida fuera hacerme de ropa de marca. No, la cuestión era que en ese entonces la economía mexicana no compensaba justamente la labor de los trabajadores, lo cual hacía que las esperanzas de construir una mejor vida fueran prácticamente nulas. Creo que esto sigue siendo verdad hoy en día.

Pero permítame explicarme en más detalle. Mi padre murió a los 22 años, días después de mi nacimiento, dejando a mi madre viuda a los 16 años. Yo crecí en una casa de una sola recámara, la cual compartía con 11 familiares: mi madre, mi abuela y mis nueve tíos y tías. Está por demás decir que la pobreza definió mi vida desde el día que nací. Y fue por eso, porque una persona de mi extracción social no podrá jamás satisfacer los requisitos para la obtención de una visa estadounidense e ingresar al país por canales legítimos, que una noche, cuando tenía 19 años, me colé por la frontera a través de un inmundo y oscuro sistema de alcantarillado.

Al llegar a Chicago, de inmediato encontré empleo haciendo todo tipo de trabajos ínfimos. Comencé también a tomar clases de inglés donde, por casualidad, me enteré que podía estudiar para algo llamado el “GED”, el equivalente a la preparatoria que en mi querido México nunca hubiera podido cursar. Para una persona que había abandonado el estudio formal a los 13 años, la prueba del GED, debo admitirlo, fue extremadamente difícil, pero logré aprobarla después de tres arduos intentos. Para cuando ingresé a la universidad, llevaba ya casi diez años en Estados Unidos.

Fue en la universidad, presidente Obama, que me familiaricé con la cultura y los valores estadounidenses. Aprendí, por ejemplo, acerca del fabuloso principio de la libre expresión, que está consagrado en la Constitución. Por medio de mis lecturas, eventualmente aprendí también que una gran cantidad de personas habían hecho grandes esfuerzos para negarles este derecho a muchos otros, que el documento de los padres fundadores, como el país en sí, es un trabajo en proceso y que, a fin de alcanzar sus objetivos, se necesitaba de personas como Ralph Waldo Emerson y Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau y W.E.B. DuBois, Noam Chomsky y Cornel West.

Fue también en la universidad, presidente Obama, donde aprendí la complejidad de las palabras: lo efímeras o poderosas que pueden ser, o lo ilusorias o edificantes que en muchas veces son. Y después, muchos años después, habiendo concluido ya mis estudios de posgrado y habiendo leído ciertos capítulos de la historia estadounidense con más detenimiento, comprendí que en este debate sobre la inmigración una pluralidad de voces —algunas iracundas, otras compasivas y otras completamente despistadas— circula en las ondas radiofónicas y televisas o aparece en los medios electrónicos e impresos. Y me di cuenta que, en este debate, una voz está excluida: la del indocumentado. No la de los Dreamers, que son americanos cien por ciento y hablan un inglés perfecto, sino la de sus padres. Personas como yo: migrantes económicos que tradicionalmente no hemos gozado de acceso a una educación adecuada y que hemos aprendido que, a fin de sobrevivir, hay que obedecer y permanecer callados.

Esta es, en breve, nuestra historia: la historia de una minoría confinada al silencio.

Y es por esto, señor presidente, que le dirijo la presente: para informarle que estamos aprendiendo su idioma. Y no es para poder maldecir, como Calibán, y regresarles el insulto a aquellos que nos tildan de “ilegales” y nos consideran seres inferiores. Es más bien para entablar un diálogo acerca de nuestros problemas mutuos, sostener un charla civilizada, quizá discutir apasionadamente y llegar así a una solución común.

Podríamos hacer preguntas. Por ejemplo: ¿de qué manera se diferencia el caso de los 11 millones de personas que en la actualidad vivimos en el clandestinaje en Estados Unidos del de algunos de los primeros estadounidenses siguiendo la iniciativa de Stephen Austin para establecerse en México, “con o sin pasaporte”? O, ¿deportarían las autoridades a esos miles de niños que vienen huyendo de la violencia en Centroamérica si, en lugar de estar llegando por México en la actualidad, hubiesen llegado a Ellis Island hace un siglo provenientes de Europa? O, ¿es este un mejor país después de que se ha separado a más de dos millones de familias? O, ¿será mi hija de tres años la próxima niña estadounidense en perder a su padre debido a la deportación?

Hace apenas un par de semanas leímos la opinión de algunos líderes de la comunidad empresarial en apoyo a una reforma migratoria. Ellos creen que cualquier reforma migratoria debe favorecer al capital y al talento extranjeros. Un poco antes, señor presidente, se había usted pronunciado a favor de una reforma migratoria más tradicional, una reforma que, más que al privilegio, tome en cuenta a los hombres y mujeres que laboran en esta nación. Esto, me parece, está más en línea con la realidad cotidiana del país. La mayoría de nosotros no hemos venido en busca de un lugar donde depositar nuestra inversión, sino en busca de un terreno fértil donde nuestras frustradas esperanzas puedan florecer. No ha faltado entre nosotros quien encuentre una estabilidad económica relativa, pero ha sido siempre a costa de su dignidad humana.

En mi caso personal, señor presidente, en lugar de riquezas, lo que encontré fue su idioma, sus libros, sus universidades. Así como usted, en Chicago conocí a mi esposa, y fue en esta bella ciudad donde mi hija nació. Chicago me brindó la oportunidad de reinventar mi vida y ahora, más de 20 años después de haber llegado aquí, sigo con el anhelo de hacer de esta ciudad un verdadero hogar.

Hacia finales del verano, presidente Obama, cuando se reúna de nuevo con su grupo de asesores para abordar el tema de la inmigración, tendrá usted la oportunidad de aliviar el sufrimiento e incertidumbre de millones de personas que han estado contribuyendo al beneficio de este país por mucho tiempo. Espero que le ofrezcan razones suficientemente poderosas para tomar medidas en el asunto, pero sobre todo espero que encuentre usted el coraje para seguir sus propias convicciones.

Atenta y respetuosamente,

José Ángel N., autor de Illegal: Reflections of an Undocumented Immigrant