Editor’s Note: Originally published in AlterNet.org, the authors of the piece approached us as well and have given us permission to reprint. The following essay is our latest installment of opinion pieces regarding U.S. policy in Central America.

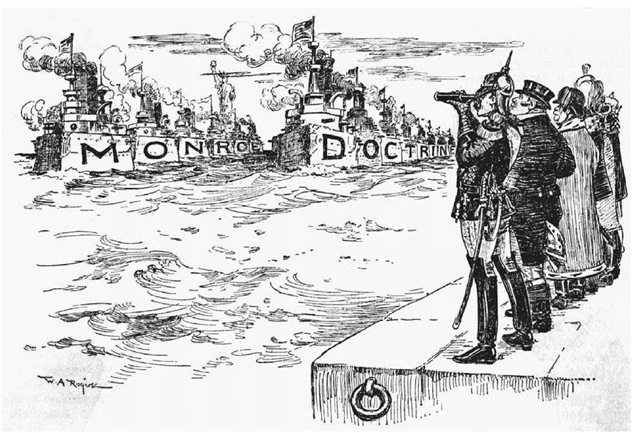

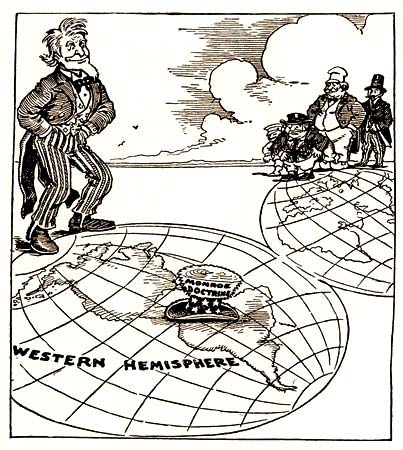

“[I]n the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States.. . to the exercise of an international police power.” —Theodore Roosevelt, 1904

It is impossible to understand the root causes of the current wave of Central Americans arriving to the United States, and therefore the appropriate U.S. response, without acknowledging the historical relationship between the U.S. and Central America. Unfortunately, the debate in Congress and in the mainstream media has largely focused on whether or not the U.S. has new obligations under international humanitarian and refugee law or a moral duty to treat non-citizen children with compassion. Vice President Biden recently referred to them as “our kids”, but he was stressing the importance of due process for the children’s asylum claims while simultaneously calling for a “Plan Colombia” in Central America. Policy-makers often tout Plan Colombia as a great success, ignoring the over 6,000 extrajudicial assassinations by Colombia’s military since its implementation in 2000. Before pushing for even more Drug War militarization, the U.S. needs to respond to this long-running crisis by first coming to terms with its history in Central America and accepting its share of the responsibility in creating the current political, social, and economic conditions refugees are fleeing.

The U.S. has long exercised control of Central America through military interventions or the financing, arming, and training of pro-U.S. local elites and their armed forces. In 1823, President Monroe declared the U.S. the sole commercial and political power throughout the Western Hemisphere. By the 1880s, many Central American and Caribbean republics were reduced to “protectorates or in effect client states” of the U.S., according to historian John Coatsworth. During the Banana Wars, the U.S. military intervened in Honduras seven times between 1903 and 1925. The 1954 CIA-orchestrated Guatemalan coup effectively sparked their civil war. It would cruelly last until 1996. In the 1980s, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala were inundated with U.S. military aid and advisers. The “Banana Republic” of Honduras became a staging ground for U.S. trained armed forces fighting leftists in the three countries it borders and so earned a new nickname – the “U.S.S. Honduras”.

The School of the Americas (SOA) is the embodiment of the U.S.’s traditional policy towards Central America—pretending to apply military solutions to social and economic problems. Established in 1946, the SOA remains the only U.S. military institute dedicated to training the security forces of one specific region of the world. During the Cold War, its curriculum was designed to “thwart armed communist insurgencies.” It continues to equate democracy with “free markets.” Graduates of the SOA include the most notorious Central American human rights violators: members of the Battalion 316 in Honduras; the murderers of Archbishop Oscar Romero, the four U.S. churchwomen and over 900 civilians at El Mozote in El Salvador; and the former and current Presidents of Guatemala (Efrain Rios Montt and Otto Perez Molina) connected to genocidal military campaigns in that country. Despite the Pentagon’s claims of change and transparency, they have refused to release the names of SOA graduates for the last 10 years. Be it Cold War or Drug War, the SOA continues to be part of the apparatus that enables U.S. allies to commit human rights violations in the name of democracy.

The role of the U.S. in the Central American civil conflicts of the 20th Century was not as much an aberration, but an escalation of long-established relations. Local oligarchies and the U.S. collaborate militarily to assure that the unequal political and economic status quos prevail. What was unprecedented in the 1980s was the scale of the civilian carnage left behind by U.S. trained and financed armed forces, and the resulting large-scale arrival of Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and, to a lesser degree, Honduran refugees to the U.S. From 1980 to 1990 the number of Central American-born people in the U.S. roughly tripled from 353,900 to 1,134,000. By 2000, the number surpassed 2 million. Although systemic violence and its accompanying destruction of economic activity is at the root of the current wave of Central American migration, the choice to flee to the U.S. instead of another country is also linked to the desire to reunite with family members that arrived during prior migration waves.

June 28, 2014 marked the fifth anniversary of the military coup (led by SOA graduates) that ousted democratically elected Honduran president Manuel Zelaya. Opposition to the coup and the resulting governments was widespread and continues to this day. Thousands of activists, journalists, lawyers, campesinos, LGBT persons and others opposed to the resuscitated fascist forces have been threatened, beaten, tortured, disappeared or killed. The U.S. worked diligently, against the overwhelming opinion of the rest of Latin America, to guarantee that the coup regime remained in power. In 2009, Porfirio Lobo was elected in a fraudulent process which was boycotted by coup opponents. In 2013, Juan Orlando Hernandez was elected in another tainted election. The U.S. quickly recognized both results. Post-coup Honduran security forces have been the recipients of increased U.S. military aid and training despite their well-known record of human rights violations and infiltration by the drug cartels they ostensibly combat. This illogical, yet familiar pattern can only be explained by the geopolitical importance of the “U.S.S. Honduras”’ to the Department of Defense. Since the coup, the Pentagon has not only built up Soto Cano Air Force Base, already the largest U.S. military base in the region, but it has also built at least three new U.S. military installations in Honduras.

29% of the unaccompanied minors that have surrendered to Border Patrol in 2014 are from Honduras. It should be no surprise that Honduras has for the first time become the number one source of Central American migration when the U.S.-backed Honduran regimes have exacerbated lawlessness, violence, and economic alienation over the last five years. The current wave of children and adults fleeing Central America is, at the very least, partly due to the continuation of the supremacy of Pentagon whim over the basic needs of the poor majority of Central America.

It is imperative to consider why Nicaraguans are not migrating en masse despite facing similar historical, economic, and imperialist obstacles as the other Central American countries. The Marines’ occupation of Nicaragua (1912–1933) spanned five U.S. presidencies, including that of Democratic icon Woodrow Wilson. During this period, the Marines created, trained, armed, and commanded Nicaragua’s National Guard while assuring that Conservative governments ruled the country, whether or not they actually won elections. When the occupation ended, the Marines passed de facto power of the country over to the National Guard, which was then headed by the U.S. favorite, Anastasio Somoza. Somoza and his family led a corrupt and brutal military dictatorship until the triumph of the 1979 Sandinista Revolution, the first and only successful popular revolution in Central America. Remnants of the deposed National Guard would then form the U.S. proxy army known as the Contras, who became infamous for their atrocities against civilians, Iran/Contra, and their connections to drug-trafficking. In 1985, the International Court of Justice would decide that the U.S. owed Nicaragua reparations for supporting the Contras and mining Nicaragua’s harbor. The ruthless efforts to topple the Sandinistas would temporarily prevail when war-weary Nicaraguans voted them out in 1990 elections. But after 16 years of relative peace (and neo-liberal policies), Nicaraguans voted the Sandinistas back to power in 2006 and again in 2012.

Despite similar levels of poverty, it is undeniable that Nicaragua’s far lower levels of violence and forced migration differentiate it greatly from its neighbors. It is also undeniable that its military and security policies have developed differently due to repeated breaks from the Pentagon’s orbit, including withdrawal from the SOA in 2012. Even the U.S. has conceded that the Sandinista “community policing” model has been successful, and is now promoting a version of it in Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala as part of the solution to the child migrant crisis. But the importation of the model is doomed to fail unless a fundamental change in the culture of the security forces accompanies it. AFGJ’s Chuck Kauffman noted last month, “Drug cartels have been unable to gain a foothold because the army and police are those same muchachos and muchachas who defeated a US-backed dictator and aspired to be New Men and New Women. Nicaraguans are astounded at the corruption and brutality of the security forces of their neighbors.”

Since 2008, the U.S. has spent over $800 million in security aid to Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador through the “Central American Regional Security Initiative” (CARSI) as well as millions more in bilateral military and police aid to each country. But when that money goes to the likes of Honduras’s cartel-infiltrated politicians and brutal state security forces is it surprising that the rule of law further deteriorates? Central Americans are suffering through increasing and extreme levels of violence, while there has been zero impact on rates of drug use in the U.S. Central American adults are risking their lives and those of their children to escape the historical and current system of violence that the U.S. refuses to recognize its role in creating. Who is more irresponsible, the parents or the Pentagon? Who is more rational, the parents or the U.S. Congress?

If the goal of the Drug War is actually to disrupt the drug cartels while safeguarding the lives of ordinary people, then resources should be refocused on drug money laundering by the Central American elites who are propped up by U.S. military aid, as well as Western financial institutions. The narco-oligarchs and the executives at HSBC, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, and other banks responsible for documented drug money laundering should currently be in detention, not child refugees and their families.

In 2013, after nearly 200 years, Secretary of State John Kerry declared the era of the Monroe Doctrine over. Despite the statement, it appears that business as usual continues for the Pentagon and its corrupt allies in Honduras and Guatemala. As record numbers of Central American refugees and immigrants are detained at the border, the media and policymakers need to take a hard look and admit that these children are the progeny of past and current armed conflicts funded by U.S. taxpayers. If the U.S. is actually going to treat the root causes of Central American migration, the conspiratorial right-wing blame on DACA must be dismissed, and the Pentagon’s standard alarmist and racist proclivity towards further militarization must be ignored. Honest, bold, and research-based reevaluations of the Drug War and overall foreign policy towards the region must first be conducted and implemented for conditions in Central America to improve any time soon.

***

Arturo J. Viscarra is a child of the Monroe Doctrine who migrated to the U.S. from El Salvador during the civil war. He is an immigration attorney and the Advocacy Coordinator for School of the Americas Watch (SOA Watch): www.soaw.org.

Michael Prentice is a student at Vassar College interning for SOA Watch. Join Michael, Arturo, and thousands of others for the 25th SOA Vigil this November, whether or not the police “allow” it to happen: http://soaw.org/november/en/.