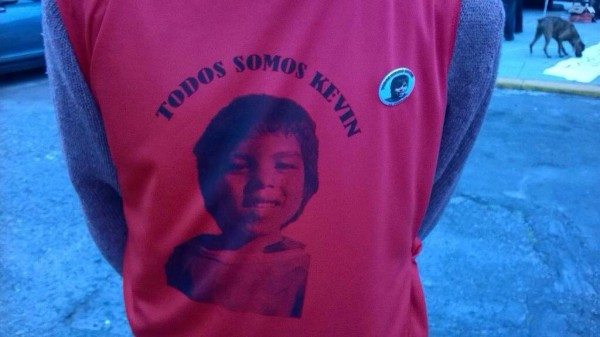

This is a story about the villas of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Not a story about the usual stigmas and stereotypes, but one about human rights. Today marks one year since a nine-year-old boy named Kevin Molina was killed by a stray bullet while he watched the Disney Channel with his siblings in the Villa Zavaleta. After a year of mourning and demands for justice, today people are saying, “¡Todos somos Kevin!” (“We are all Kevin!”)

The Battle Field

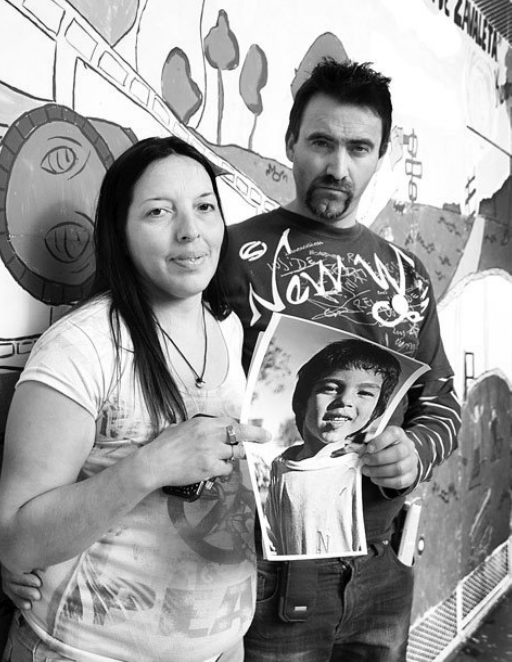

Kevin’s mom Roxana is a mother of 13 and a grandmother of 10. She lives with her husband, Claudio, and six of her children in a one-room, one-window house measuring 28 square meters.

The house sits on a tiny pathway, not on a street, which is common in villas as they are informal neighborhoods that exist outside the formal system.

On September 7, 2013 at 6:00 a.m., two foreign gangs entered Villa Zavaleta and began to fight over a vacant house. Claudio woke up and complained to Roxana about the noise. She went to the window to survey the scene and saw six or seven armed men entering the house across the pathway from hers, located about 100 meters from the police hut. “No one lives there,” she said to them. “Don’t worry, ma’am,” they said. “This has nothing to do with you.” Claudio went to work at 7:00 a.m. and everything seemed fine. Another group of armed men soon arrived and Roxana and her children began to hear gunfire, at least 30 shots. Then, silence. The police walked over to the house and kicked a toy truck against the door of the house to see if anyone would respond. Silence. The police retreated to their hut and one neighbor overheard them say, “Let them kill each other.”

The second gang returned to the scene and more shots were fired, this time faster and louder. The kids were holding onto each other tight as one bullet entered the house and stuck a dresser. Roxana later found another bullet in the closet. Kevin got out of bed, pointed to the stereo and said, “They better not hit the speakers.” Roxana told him to get back in bed and went to the bathroom. When she came out, Kevin was on the ground under the table. Roxana thought he was hiding, she saw him jerk and she said, “What’s wrong?” Then, she saw the blood and heard his short, tiny breaths. She picked him up off the floor and ran out of the house to the main plaza yelling, “A car please!” If she had called an ambulance, she would probably still be waiting. A neighbor rushed her to the hospital. Kevin was already brain dead. His heart stopped and started 16 times before he finally died.

Why Call the Cops?

There were eight 911 calls made about the fighting in Zavaleta that morning and no response from police. The transcripts, obtained by La Garganta Poderosa, a monthly magazine that is part of a larger social movement, reveal how much time the 911 operators spent trying to figure out where the complaint was coming from. Because there are no street names or official addresses, there is no efficient way to describe the scene. The operator asks repeatedly, “Where?” and the callers all say “Block 4, in front of the plaza.” Three hours of fighting, 150 bullets, 100 meters from a police hut, and no police response.

The police stationed in Villa Zavaleta claim they didn’t hear the gunfire because of the rain. When Roxana returned from the hospital that day without her son, the police had entered her home investigated the scene. Two cell phones and 100 pesos were missing. The Ministry of Security never conducted the internal investigation that they promised.

Deadly Stigmas

The news of Kevin’s death did not appear on the national TV station until eight days later, and received very little coverage compared to similar cases at the time. Mass media chooses to focus on villa stereotypes, linking villas to crime, drugs, narcotrafficking and murder with very little context. During dinner table conversation, the topic of “la inseguridad” is as common as the weather or the exchange rate. The media fuels fear of “the other”, the villeros, and generates a negative stereotype about the entire villa population in the general public.

The villas are used for fighting between narco gangs the same way that deserted village streets were used for fighting between rival cowboys in the wild West. There is no police protection and there is no press. What happens in the villa stays in the villa.

“Not One More Kid, Not One More Bullet”

The people of Villa Zavaleta created a copwatch system in order to keep their neighborhood safe from this type of institutional inaction with help from La Poderosa. The goal is to expose forced entries without search warrants and denounce abuse from authorities. So far there have been over 200 complaints of abuse.

What these people are asking for is simple: decent living conditions and safety. Villeros from all over Buenos Aires participated in a hunger strike early this year demanding that the city government comply with the urbanization law, which guarantees them paved streets, electricity, gas and new schools. Although the government agreed to comply, so far nothing has been done.

Kevin was a 9-year-old boy with two loving, hard-working parents that wanted the best for him.

Until the rest of the society that lives outside the villas recognizes the realities of these neighborhoods and until the state takes responsibility for providing basic human rights, tragedies like this one will continue to happen.

Photos and quotes from La Vaca.

***

Taylor Dolven is a regular contributor to Latino Rebels. You can follow her @taydolven.