“…porque tus anhelos no bastaron para borrar el color de mi piel en las manos del mundo.” -Irma Pineda

“Did you hear about the rose that grew from a crack in the concrete? Proving nature’s laws wrong, it learned to walk without having feet. Funny, it seems to by keeping its dreams; it learned to breathe fresh air…”-Tupac Shakur

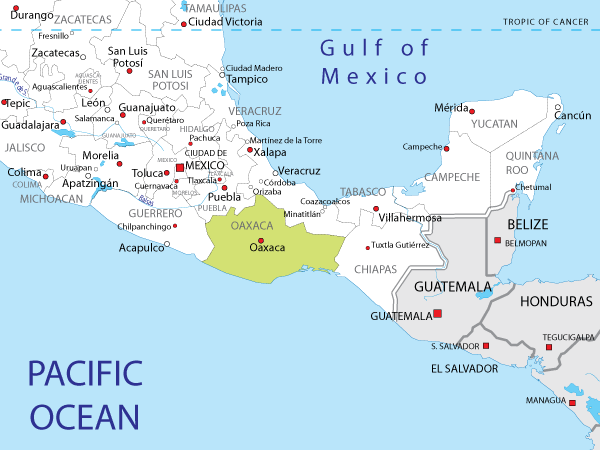

I was asked by a good friend to write a piece about Oaxacan indigenous culture in the United States, and I have been thinking about his request all day long. Oaxaca is a southern state in Mexico. Its people have experienced mass migration as a result of global capitalism, which is manifested through neo-liberal policies such as NAFTA. Many indigenous Oaxacans migrate to the United States, especially to the states of California and Oregon.

I struggled all day to define Oaxacan culture in three or five paragraphs. Oaxaca has so many cultures, ethnicities and races. It is hard to combine them in one essay. For instance, I could talk about the Guelaguetza—the biggest cultural festivity in Oaxaca or give a brief description of Oaxaca’s sixteen indigenous ethnic groups and Afro-Oaxacan communities, multiple dances and the incredible food. I could sell you Oaxacan culture as many Mexican governmental tourist programs have done. As a Mixtec-Oaxacan migrant, I think tourist propaganda springs an idealistic portrayal of my culture; it romanticizes indigenous peoples. My culture is beyond this.

It is impossible for me to talk about Oaxacan culture without sharing my experiences as an Oaxaqueño and Mixtec migrant. I was born in the Mixtec region of Oaxaca in a community named San Francisco Higos. I came with my family to Oxnard, California back in 2003. During my time in Oxnard, my parents worked in the agricultural industry. We lived in crowded spaces for our first three years. My brothers and I didn’t have our own beds. We slept on a carpeted floor and covered ourselves with our cobijas. At school, as indigenous oaxaqueños, we were discriminated against by other Mexicans who said diminutive remarks such as oaxaquita or indio. Despite not having a formal education, my mother made sure my brothers and I were nurtured in an educational and cultural environment. We talked about economics and politics at the dinner table; we talked about community duties; we also talked about our community’s art and music. We attended our migrant community parties in Oxnard where we danced chilenas and we dressed up as diablos with chivarras. Based on United States demographic data, my family could be described as “poor” but our history, experience and community enriched us.

This is the case of many indigenous people living in California. In Ventura County, where the city of Oxnard is located, there are more than 20,000 indigenous people. Many of them come from Oaxaca and the Mixtec region. Oaxacans in Oxnard work as farm workers in the agricultural fields. According to the Ventura County Crop Report, the county’s agricultural industry generated a value of over $1.9 billion in 2012. Apart from being low paid and many being undocumented migrants; indigenous farm workers endure harsh working conditions that lead to serious health problems. According to Seth Holmes in his book Fresh Food, Broken Bodies, farm work is an emotional and physically draining occupation that causes suffering on the bodies of workers and endangers their life. Women in agriculture also confront unequal treatment such as sexual harassment and abuse by their male co-workers. There is nothing romantic about being an indigenous Oaxacan migrant in the United States.

So why am I telling you this when I was asked to write about Oaxacan indigenous culture? I am writing this because historically our culture has been our agency. Despite these labor demands and poor living conditions, indigenous people have reproduced community cultural traditions such as music, food and big celebrations in both the U.S. and Mexico. I grew up listening to corridos performed by the group Acción Oaxaca that narrate the nostalgia that Oaxacan migrants in the United States feel when they think of the land they left behind.

I also grew up listening to Mateo Reyes, a Mixtec musician from San Martín Peras who narrated his experience as a Mixtec migrant through his chilena songs.

More recently, I am hooked on Miguel Villegas, a Mixtec rapper who spits in English, Spanish, and Mixteco.

This past summer, I attended a Guelaguetza organized by indigenous leaders in Oxnard, and my pride as an indigenous person was intensified by the traditional dances from the Zapotec Tehuantepec region and that of Pinotepa Nacional from the Oaxacan coast, where many Afro-Mexican communities are located. During the same summer, I also attended an Oaxacan Studies workshop at the UCLA Labor Center that was organized by Oaxacan indigenous migrant scholars dedicated to the study of Oaxacan migration and culture in the United States and Mexico. I recently received news that Zapotec scholar Rafael Vásquez is publishing a book with William Pérez about Mexican indigenous migrants in U.S. schools. We are continuing the cultural knowledge from our communities through U.S. institutions.

So then, what is Oaxacan indigenous culture in an era of global capitalism? Oaxacan indigenous culture is what I perceive to be‚a rose that grows from concrete. Despite these economic and political structures that tend to limit our life and damage our bodies, we still find refuge in our traditions. I think every Oaxacan migrant has different experiences but as indigenous people, I think we all change our ways of life according to our necessity and we find ways to live by whatever means necessary. We have been doing this for thousands of years.

***

You can follow Noé on Twitter @noehcutiepie.

Hello Noe, I work with the indigenous Oaxacan farm workers in Maneadero, Mexico. We do aid work to the best of our ability, but seriously lack understanding of the culture. I’ve Googled my way through this ordeal, but could seriously use insider knowledge. Please add me on Facebook (Cheree Giacopuzzi) if you would be willing to discuss this further with me. We would like to develop medical clinics specifically for the Oaxacan immigrants into Northern Mexico, but need a little insider help. Thanks!