Reading about Mexico reminds me of El Salvador. Older Salvadoran sensations —the smell of rotting flesh mixed with the sweet fragrance of almond trees, the sight of young faces burned into half skeletons that look like the masks our kids wear for Halloween, the unforgettably sad sound of a dead student’s mother screaming without ceasing— insinuate themselves as I read other stories about the mass graves of Mexican students killed by their government. This news affects me differently from the nonstop reports about the more “sanitized” warfare of drone strikes against “terrorists.” One major difference: my stomach knots as I read the articles about this latest mass killing in Mexico, a country that barely had a military in the 1980’s, when those Salvadoran almond trees became the trees of the knowledge of good and evil.

The difference in reading experience mirrors the difference between our news and perceptions about Mexico and our news and perceptions about other Latin American countries. Even though no country is closer to us in terms of sharing both a border and a massive population of its nationals living here, mass murders by Mexico’s government are reported, read and treated far differently than real and alleged human rights violations in other countries in the hemisphere—all of which spells more terrible news for Mexico, and for many of us here.

In Mexico, our failure to recognize the real dimensions the Mexican crisis means we’re blind to an equally disturbing fact: our government’s continued use of our tax dollars in the Drug War pay for the training, guns and bullets that slaughtered those students. This despite the fact that some of the same former Mexican presidents who received billions to fight that same Drug War now say that that war is a trillion dollar failure of titanic proportions. Less heard are the cries of the families of the students buried in the mass graves of Guerrero, who join Mexico’s more than 80,000 Drug War dead, thousands of whom were journalists, priests, human rights advocates and others whom like the students, were killed by government security forces we help fund. Viewed through a regional hemispheric lens, the children and young people migrating here from Mexico and Central America are walking, talking reminders of our utterly failed and extremely biased policies in the region.

Earlier this year, I traveled to Venezuela several times to cover the widely-reported conflicts there. I did so because I sensed something was not quite kosher about U.S. media reporting on students in Venezuela, who, instead of following the tradition of fighting U.S.-funded projects like those in Mexico, are actually the recipients of U.S. funding. After reading this week’s violence in Mexico, the journalist in me couldn’t help but ask, “What would happen if police or other security forces of the Venezuelan government killed 43 students and buried them in a mass grave?”

The journalist’s answer I came up with is informed by what we saw during last summer’s upheavals: high profile denunciations by global human rights organizations, interviews with Venezuelans in Miami and front page headlines with the word “Killings” as the operative verbs next to sentence subjects and objects like “Students” and “Maduro Government.”

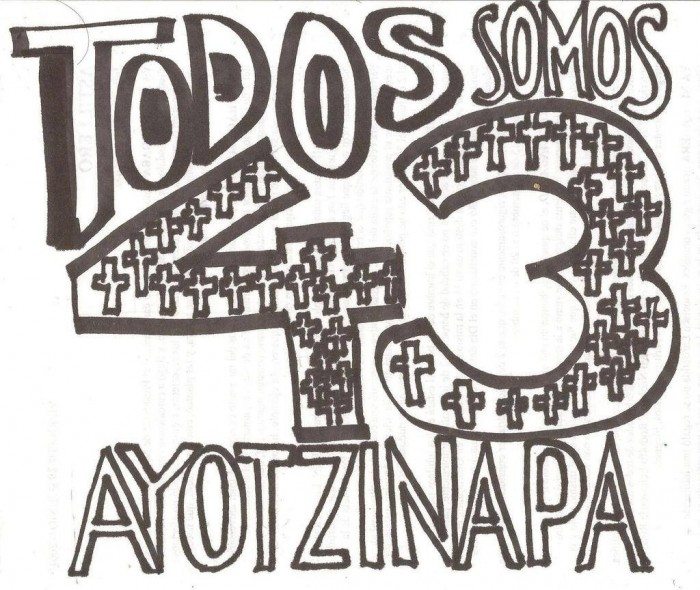

On one September day just two weeks ago, an estimated 43 students are alleged to have been disappeared and killed by Mexican police linked to drug cartels. That is equal to the total number of people killed in Venezuela during the 2014 protests—at least half were allegedly killed by paramilitaries and students opposed to the Venezuelan government. All 43 in Venezuela were killed over the course of not one day, but 160 days or four months. Looking at the media coverage and the official responses from government and non-governmental institutions, one would think that Venezuela was Mexico or wartime El Salvador. Such a distorted understanding of regional realities among the citizenry of such a powerful country enables those perpetrating slaughter in Mexico to continue doing so.

Despite all this terrible news, I do think that the radical disproportion in both reporting and policymaking circles will soon face a major challenge: students themselves. In line with the Salvadoran and U.S. youth who altered U.S. policy in El Salvador and following the dynamic activism of students leading social movements around the world, the young people of Mexico are showing great courage before their country’s critical situation. With millions of DREAMers and other U.S. students and others engaged with Mexico through familial relationships, it’s only a matter of time before the same kind of activism that fought and exposed the two million deportations and other devastating immigration policies of the Obama Administration starts to inform Obama and the next U.S. president’s foreign policy in Mexico.

Such a combination —Mexican and U.S. youth joining forces to stop the madness— has the potential to change not just Mexico, but the United States, as we are witnessing with the decline and fall of traditional Republican and Democratic party immigration politics. Increasingly, Latinos are and will continue engaging far and beyond the ballot box, beyond the sterile, suffocating smell of the militarized border as the winds of the south awaken us with a deeper knowledge of the good and evil hidden in the smell of almond trees.

***

Roberto Lovato is a writer and a Visiting Scholar at UC Berkeley’s Center for Latino Policy Research. You can follow Roberto on Twitter @robvato.

Good piece, sorry Santiago missed the point and accepted US propaganda as fact.