This essay does not judge or condemn Luis Muñoz Marín.

We all know that President Barack Obama, Governor David Patterson (New York) and Congressman Trey Radel (Florida) used cocaine, Mayors Marion Barry (Washington, D.C.) and Rob Ford (Toronto) smoked crack, and innumerable politicians and CEOs do a little “something something” on the regular. But 70 years ago, a divorce, an abortion, or a drug addiction could end any political career.

It almost happened to Governor Luis Muñoz Marín of Puerto Rico.

In 1934, Pedro Albizu Campos led an island-wide agricultural strike that brought the insular economy to a standstill, and ended only when the sugarcane workers’ wages rose to $1.50 per day—more than double what they’d been receiving. The U.S. reaction was immediate. An Army general named Blanton Winship was sent down as governor, and a Naval Intelligence officer named E. Francis Riggs was installed as Chief of Police. They immediately militarized the Insular Police, shot Nationalists in broad daylight, murdered 17 civilians in the Ponce Massacre and on October 28, 1935, Riggs declared “War to the death against all Puerto Ricans.”

Albizu Campos was arrested and sentenced to 10 years in USP Atlanta Penitentiary. Other Nationalists were imprisoned, harassed, fired from their jobs and followed all over the island by the FBI. Some of them “disappeared.”

But this was not enough. The U.S. needed further control. They had to contain this “Nationalist problem,” or they’d lose the island forever.

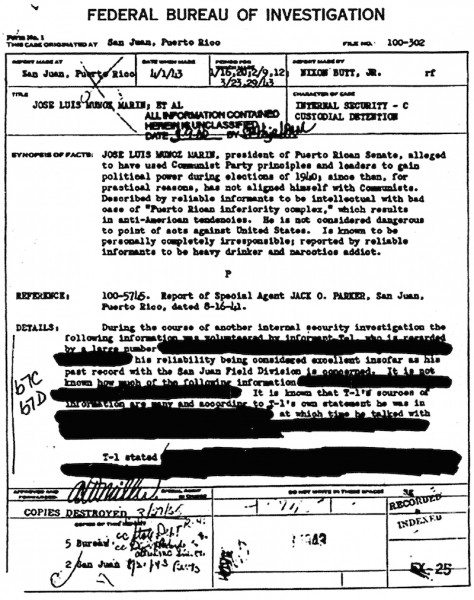

That’s when J. Edgar Hoover, the king of the carpetas, rode in with his FBI cavalry. He followed every known Nationalist all over the island. He investigated mayors, teachers and Catholic priests. Barely three weeks after Muñoz Marín was elected to President of the Puerto Rican Senate, Hoover commanded his San Juan office to “obtain all information of a pertinent character concerning Luis Muñoz Marín and his associates.” He later issued a second demand for “a thorough and discreet investigation by the San Juan Office.”

The reports poured in immediately:

Luis “has no profession.” Luis is “absolutely irresponsible financially. He never has any money in his pockets and never thinks of his responsibilities.” He “never accepted the responsibility of marriage or of his family, and for years has not contributed to the support of Muna Lee (his wife) or his children.” During the last six years (1934-1940) he “abandoned his home and is living with his mistress, Inez Maria Mendoza.” He is “utterly unprincipled” with “no ideals whatsoever,” and has been “a member of four different political parties during his political career.”

As President of the Puerto Rican Senate, he is a known “heavy drinker” who “goes on protracted drunks which last from two or three days to two or three weeks,” and whose “bill for whiskey alone runs around $2,000 a year.”

On one occasion Luis “got thoroughly drunk with Vicente Geigel-Polanco, the Majority Leader of the Senate, in the Normandie Hotel.” On another he arrived at the Escambrón Beach Club at 8 p.m. where “he ordered drinks,” then “he ordered more drinks,” then “he swept all the drinks from the table,” then “he swore at his friends” and finally he left at 1 a.m., “so intoxicated that he was hardly able to walk when he left the place.”

When told by the Escambrón that he owed them $650, Luis told them they could get “a $650 tax deduction” for it. He also had a $300 bill at the Condado Hotel and a $200 bill from RCA, neither of which had been paid in five years.

But J. Edgar Hoover was an old hand at discrediting people and destroying their careers. He knew this dirt about “drinking” and “unpaid hotel bills” was small potatoes. He needed something big and demanded something big, for 2½ years…

And finally he struck gold.

On April 1, 1943, Hoover received multiple reports from “reliable informants” that Luis Muñoz Marín was a narcotics addict. Here is the first report:

A second report showed that Muñoz Marín had faced charges of morphine addiction in a public assembly of his own party, in front of hundreds of party members.

A third report showed that Muñoz Marín was known as El Moto de Isla Verde (The Junkie of Isla Verde), who started smoking opium in his Isla Verde home and years later in the governor’s mansion every weekend. That report also showed that he’d been “involved in an important narcotics case, but nothing was done because Muñoz Marín would fire all members of the Insular Government Narcotics Bureau if prosecution were even contemplated.”

Now, Hoover had Muñoz Marín exactly where he wanted him. Muñoz Marín was a narcotics addict who smoked opium every weekend. He’d gotten caught in a narcotics deal—and he’d used his public office to bury the entire matter.

The FBI had everything it needed. They didn’t investigate any further or prosecute Muñoz Marín’s narcotics case—because with these three reports (narcotics addiction, narcotics sale, obstruction of justice) the FBI could end Muñoz Marín’s career at any time. With a one-page report they turned the political leader of Puerto Rico into a U.S. sock puppet.

Evidence of this puppetry came immediately.

In 1943, within weeks of the FBI reports, Muñoz Marín flip-flopped on the issue of independence for Puerto Rico. In both 1943 and 1945, Muñoz Marín not only opposed the Tydings independence bill, he traveled repeatedly to Washington, D.C., to lobby against the bill.

By 1948, the transformation was complete: when Muñoz Marín told reporters that “the only serious defect” in U.S.–Puerto Rico relations was the law that prevented the island from refining its own sugar.

Also in 1948, Muñoz Marín convened an emergency legislative session to pass Public Law 53, also known as La Ley de la Mordaza (the Gag Law). Public Law 53 made it a felony to speak in favor of Puerto Rican independence; to own or display a Puerto Rican flag (even in one’s home); to print, publish, sell or exhibit any material which might undermine the U.S. government; or to organize any society, group or assembly of people with a similar intent.

By 1950, in just two years, Muñoz Marín used Law 53 to arrest over 3,000 people without any evidence or due process, and to imprison many of them for 20 years.

He told the New York Times that these 3,000 people had been arrested for “conspiracy against democracy helped by the Communists,” and denounced their “lunacy, fanaticism and irresponsibility manipulated for the benefit of Communist propaganda.”

He used Law 53 to arrest his political opponents, and to intimidate anyone who didn’t want to vote “Commonwealth” during the 1952 status plebiscite.

When newspapers called Luis a traitor and prominent lawyers called Public Law 53 a Gag Law, which violated free speech and invited policemen to break into people’s homes, Muñoz Marín responded that “this law is precisely to prevent anyone from gagging the Puerto Rican people through fascist threats of force. And I have asked the FBI to enforce it.”

This was the same FBI that had records of Muñoz Marín’s personal narcotics addiction, and his own criminal narcotics activity.

The same FBI that had him (and through him, the entire island) on a dog leash.

El Moto de Isla Verde was turned into a doormat by the FBI. Every U.S. investment banker, sugar cane millionaire and politician wiped their feet on that doormat, whenever they entered the governor’s mansion.

This essay does not judge Luis Muñoz Marín for his drug addiction, or condemn him for smoking opium in La Fortaleza. But the consequences of his drug addiction were shared by every person in Puerto Rico, their children and now their grandchildren.

According to legend, Nero fiddled while Rome burned.

According to fact, Luis Muñoz Marín smoked opium while his country was bartered away.

***

Nelson A. Denis is a former New York State Assemblyman and author of the upcoming book, War Against All Puerto Ricans.

Editor’s Note: Initially, the third FBI report cited in this piece stated that Muñoz Marín was said to have only smoked opium in the governor’s mansion. That was not accurate. The third FBI report also said that he had started years before in his Isla Verde home around 1943 before he became governor in 1949, where he continued, according to the FBI report. We want to thank @BrayanJSanchez for raising the question with us and the author, who confirmed this chronological oversight. The article has been edited to accurately reflect the third FBI report.

I found this article to be very insightful. As a poster stated above, its very alarming the tactics that the FBI used to control the destiny of nations. This is the type of blackmail tactic that has been going on since the beginning of civilization to control someone in power, or get them to do a favor. It’s actually very sad that someone’s own personal addiction can then be used against them which in turn alters the future for millions of people.

I am concerned regarding some of the above comments from those debating the factually of this article. I see comments attacking this article, and then not providing follow up references. Additionally, the references that were provided have been ignored. Though I don’t claim to be an expert in Puerto Rican history, it’s a topic that I’ve become interested in lately due to some recent family events. What I do know is in my experience in research and analyzation is that the only way to support a claim is with sources ( which this article seems to have) and anyone claiming to refute them should provide something more than opinion or an antagonization.

Jaivin419 Thank you. Someone had to say it. We truly appreciate it!

Not only he betrayed the people of Puerto Rico but also betrayed the memory of his own father, Luis Muñoz Rivera, who was the elected head of government of the Province of Puerto Rico in 1897. His whole government was overthrown by the US invasion when Puerto Rico was at peace and celebrating the Carta Autonómica (a special law giving the island autonomous powers within the kingdom of Spain) His father was loyal to Spain until the end, his father did not conceived Puerto Rico apart from Spain because Puerto Rico was Spain, he declared in 1898 ‘We are spaniards” (La Democracia, newspaper 1898). Sadly, in 1952 Luis Muñoz Marín helped to create a puerto rican identity outside the spanish identity, a colonial identity favoring US colonialism and its invasion.

Wow I’ll never image that the republicans will go that low. Than

Lincoln was a cocaine & crack user.

I would be careful with any reports coming from Hoovers nefarious hands. I don’t dismiss that he may have used Opium many Artist,Bohemians etc, did in that era. I question the accuracy of the extent of his use. Drug users seem to be stereotyped as long term or heavy users. I once worked with a Heroin addict that used his drug sparingly and his use did not impede or interrupt him from his duties. Would anyone minus the drug use have been able to escape the oppression of his Office in that era? I believe that paranoia within government over the “Red menace” would have rendered same results. Oppression on democratic principals makes it impossible for the function of democracy.

Are you forgetting that Lincoln was himself a Republican?

La historia se puede ver con el cristal de quien la mire…… es injusto señalar a una persona que trajo inmenso bienestar a nuestro pais….. haciendo uso de informacion que aun es incierta o que la misma pueda ser tomada como veraz…. como puede mancillarse la historia de nuestro pais o enaltecer la misma si nosotros como nacion no tomamos control de lo que hablamos o escribimos grandes imperios pueden ser destronados con el uso de la lengua me parece desleal a nuestra historia el levantar velos de incertidumbre…..

Manana llevare mucho opio a Fortaleza y a la Legislatura. Si el opio pone a trabajar a la gente asi y a obtener resultados; …..pues que viva ell opio y LMM!

Mas bien me parece un articulo de un buscon de fama.

A monumental piece of laughable propaganda.

si y Kennedy fue matado por la mafia porque su familia traficaba con Whisky en la época de la prohibición, que falta de respeto es esta? Y después de Hoover que se comentaba era Homosexual y por eso no juzgo a todos los homos.

No le creo ni “jota” al FBI. En una sola hoja de escrito pueden tener anotadas cien mentiras y 200 canalladas. El escritor (historiador) debe tener cuidado con esas referencias. veo que tiene otras muchas, pero me parece que ninguna de esas sustenta esa idea del “muñoz drogadicto”. Ahora, es bien conocido en PR lo mucho que bebía, que era mujeriego y algo inresponsable. Por favor, Dra Tió, las victorias de la maquinaria popular tienen explicaciones mucho mas complejas. Yo si creo que Don Luis fue un traidor, complice de las torturas a Don Pedro y enteró un buen momento para la independecia…Pero “la historia contractual” en un país tan colonizado, con tantos politiqueros, ay no quiero escribir más.

Si puedo compatir algo para su consumo. Don Luis bebia ron como cualquier otro puertorriqueno. Aprendio a fumar Marijuana en Nueva Yor con su esposa Mona Lee.. Para esa epoca, consumirla no era pecado. Si lo hizo o no en La Fortaleza es para ser probado. Este articulo solo presenta lo que EJH dice. Me encantaria conocer sus reportes sobre los Kennedys. Empezando por su papa joseph

Jaivin419 The same exact references that were cited by the author can be used to also challenge what is being expressed in the article. What those references and citations state do NOT translate into what is being expressed by the author. The article is specifically charging Luis Munoz Marin as having been an Opium Addict. All the while he was Governor of Puerto Rico.

Read the citations used. How does an FBI report that clearly states information was made courtesy of a confidential informant, or alluding to a statement in a speech that was expressed in a generic/general way and not to LMM specifically, translates into a fact being that Luis Munoz Marin was addicted to Opium during his Governorship?

It doesn’t. It has simply been translated to convey this so called fact. That’s not the way it works. You, and many others out there, may want to revisit practicing on their research and analyzation skills. We are not all stupid out here. A more substantiated evidence is required to make such a bold statement as what has been perpetuated by the author of the article.

Just for the record, I support and am for a complete and total sovereignty for the island of Puerto Rico. This belief does not translate to embracing an unsubstantiated account about a person who was stood on the other side of that political stance during his reign as Governor and was a far more complex individual (as was Don Pedro) than how either of them have been painted as in this rendition of a history of the Puerto Rican independence movement during the 20th Century.

Luis Munoz Marin, el más grande traidor de nuestra patria, rehusó apoyar la independencia para PR no porque fuera un adicto sino porque directamente estuvo envuelto en un caso de narcoticos y por sus intereses financieros en las monopolies de azúcar que sufragaban sus vicios. La FBI y USA uso esa info para obligarle firmar la Constitución de PR sin haberla leído después de numerosos cambios y le apoyaron ganar elecciones robadas! El nombre de Luis Munoz Marin debe borrarse de la historia de PR! Encarceló a Albizu y a más de 3,000 nacionalistas y por su gran avaricia y vicios y mediocridad; perpetuo la colonia!

Los gobernantes se eligen para hacer cumplir la voz del pueblo que los elige para el bienestar de la nación; no para traicionar los intereses nacionales ni vender la patria con una constitución ilegal que si fuera juzgada en un foro internacional…. obligarían a USA a darle independencia a PR por su doble fraude! El Tratado de París y La Constitución de PR!

Albizu Campos era un genio y abogado magistral que leyó y estudio todos esos docs! Amaba a PR de verdad! Marin era un bohemio cuyo interés fue siempre su propia piel y amaba Greenwich Village, no PR! Su farza fue convencer a los jibaros que sin USA no eran nada y que los gringos le darían pan! Nunca les dijo que PR hacia billones en azúcar 98% de ganancias brutas! Así DOMINO… PR con su farza ideología de un Estado Libre Asociado (PR no es estado, no es libre y no está asociado pues es meramente una colonia)

To: Nelson Denis, Thank you for publishing the book, The War Against All Puerto Ricans”! When a whole nation is suppressed psychologically, politically, economically and by brutal force and intimidación, to accept a colonial rule after an illegal invasion with no end in sight to the subversive forces that control the colonial status; its gratifying to read about how this colonial status developed into one of the greatest “sweat shop” in the world with the blessings of a Commonwealth” givernment! Common wealth is shared; a tax free heaven of 115 years and counting is no Commonwealth when USA refuses to bail out the swear shop after a decade of reccession!

The only weapon against ursury is education and enlightment of the masses. Usa is a great nation; but its colonial rule in PR is cruel!

I hope to see Puerto Rico free, independent and thriving as a sovereign nation! One hundred and fifteen years of colonialism cannot eradicate an illegal invasion, no, not now, not ever!

Puerto Ricans love PR; they do not love the USA! And they know it!

Where in hell the people that claim is a myth these horrendous evidence weren’t true. never or were in part accomplice of the written information.thank you cery much nelson denis.

[…] How Luis Muñoz Marín (and His Addiction to Opium) Enslaved Puerto Rico […]

No se puede defender lo indefendible… Y la evdencia esta… El trajo la falsa ilusión de bienestar, sabiendo que el ELA estaba condenado al fracaso ab inicio. Vendio su patria por mantener su reputación ya acabada…. Los hechos hablan y la historia con sus evidencia existe. La reto a que busque para que despierte

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.

Of course none of this can be proven to be true and is authored by a Cuban Puerto Rican. This is all that you need to know about this article.

Edgar Hoover era Afro decendiente y lo negaba.

[…] the right to self-determination that democracy promises. This began prior, with legislation such as La Ley de Mordaza, Puerto Rico’s “gag” law was enacted in 1948 and lasted for nine years. This law allowed for […]