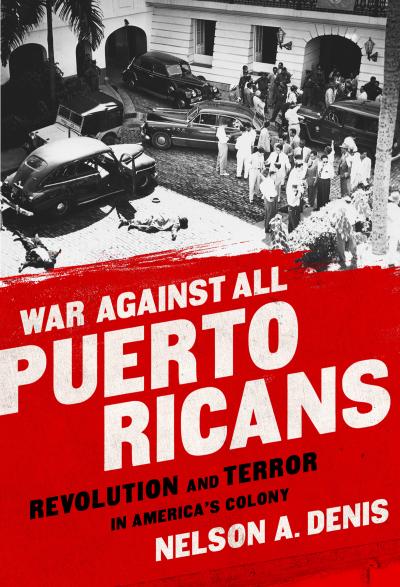

Recently, I had the great pleasure of speaking with Nelson Denis, author of War Against All Puerto Ricans. I have long had an interest in the subject of Puerto Rico’s 1950 Revolution and whether you are familiar with this largely suppressed moment in our history or not, Denis offers sharp and exciting insights on mid-century Puerto Rico. In our conversation, we spoke about the book, about the relationship between Puerto Rico and Cuba, about the modern independence movement, the complexity of Puerto Rican identity and much more.

JM: The first thing that came to mind when I saw your book was that it was in English. Did you feel it particularly important to have the book be in English? Are there plans to have it translated?

ND: I 100% agree that my own book War Against All Puerto Ricans should be translated into Spanish. I have repeatedly made this point to my publisher—since the book is about Puerto Rico, where the dominant language is Spanish.

I also emphasized to my publisher that while Borders existed, the most profitable of all the 500+ Borders stores, was the one in Plaza Las Americas.

Unfortunately, that decision is out of my control. Hopefully they will publish a translation—because the people of Puerto Rico, and the students, and the young generation of Puerto Ricans, deserve to know their own history.

JM: What misconceptions do you feel people inside and outside of Puerto Rico have concerning Pedro Albizu Campos?

ND: As an important historical figure whose life and struggle were never fully documented, there are many misconceptions about him. The most frequent one I’ve encountered is that he was “anti-American” due to the racism that he personally suffered, particularly while in the U.S. Army. That allegation is wrong on several levels.

- Albizu was not anti-American; he was against American ownership of Puerto Rico. This is a reasonable distinction, along the lines of “I don’t mind your hand, but please take it out of my pocket.”

- The U.S. Army would not have been Albizu’s first encounter with racism. Surely one year at the University of Vermont and six years at Harvard gave him ample exposure to overt and subtler forms of racism, snobbery, and discrimination.

- To brand Albizu’s politics as a personal response to racism is to trivialize and ignore the larger issue: U.S. appropriation of Puerto Rico’s land, treasury, monetary system, natural resources, tariff structure, legislative authority, and right to national self-determination. To resist this is not a “personal vendetta.” It is common sense.

Another misconception about Albizu Campos is that he failed to attract and offer concrete solutions to the struggling poor and working class people, and was thus unable to spread his revolution to the masses. But solutions are precisely what he offered, in a highly detailed manner.

He did it when the workers of the Federación Libre del Trabajo (FLT) asked him to lead and negotiate the 1934 island-wide agricultural strike. He did this, and achieved a stunning victory—the sugarcane workers’ wages doubled to $1.50 an hour.

It was precisely because Albizu delivered this “concrete solution to the working class” that the U.S. militarized the insular police force, and arrested Albizu Campos. From 1936 until his death in 1965 he spent 25 years in jail. The other four years, he was surrounded 24 hours a day, seven days a week, by a squadron of FBI agents. They even passed a law —Public Law 53 (La Ley de la Mordaza)— to further silence him, and interrogate anyone who came into contact with him. That is what made it difficult for Albizu to spread the revolution to the masses. Not his lack of concrete solutions.

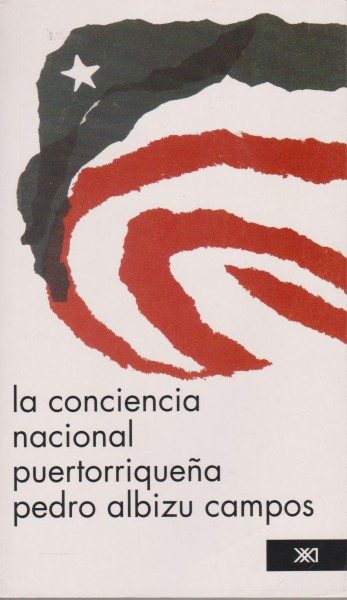

The book La conciencia nacional puertorriqueña, compiled by Manuel Maldonado-Denis (no relation to me) contains a nine-page “Manifesto del Partido Nacionalista,” written by Albizu Campos, which specifically details a program of agrarian reform; bank regulation; tariff, coastal and maritime control; legislative authority and much more. The book also contains a 98-page “Response to the Brookings Report,” which amplifies on every point in the Manifesto.

It is thus apparent that Albizu’s concrete solutions for the working class —and not his “lack” of solutions— were the reason he spent almost his entire life in jail.

JM: How did the Revolution of 1950 in Puerto Rico and the one in 1959 in Cuba affect the U.S.’s treatment of both places?

ND: The U.S. response was shaped by several forces:

- the U.S. had economic interests and corporate investments in both islands

- both islands had great geo-political military value

- Cold War hysteria (particularly in 1950) was high

- the islands (particularly Puerto Rico in 1950) were separated from the U.S. by an ocean, a language and a media gap

Although the 1934 Cuban-American Treaty of Relations ostensibly repealed much of the 1901 Platt Amendment, everyone knew that the U.S. corporate and military presence in Cuba was overwhelming, so the U.S. had deeply vested interests in both islands.

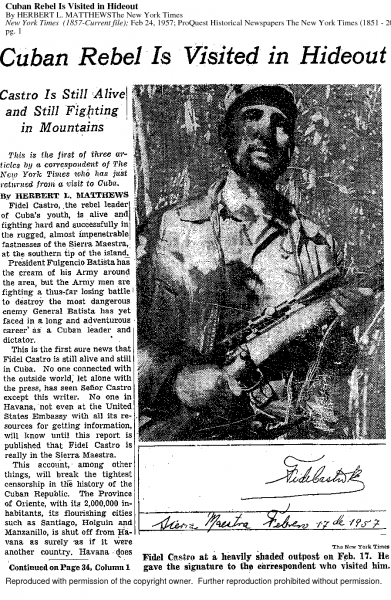

At first, the coverage of the Cuban Revolution was reported sympathetically, even romantically, by New York Times reporter Herbert Matthews.

When Castro allied with the Soviet Union, and confiscated billions of dollars in U.S. corporate assets (including Coca-Cola and Exxon), the U.S. reversed its position on the new Cuban regime. After the Bay of Pigs fiasco, it continued its crippling economic embargo.

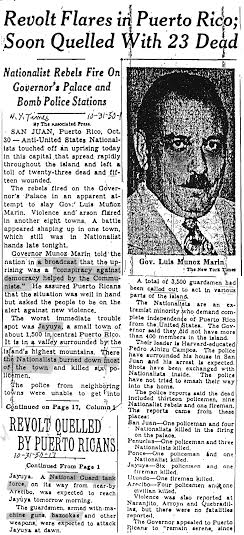

The U.S. response to the Puerto Rican Nationalist revolution, just a few years earlier, underwent no such evolution. U.S. repression was immediate and unambiguous.

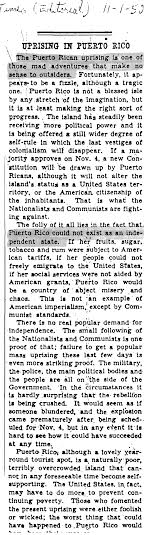

The Times ran an immediate editorial on November 1, 1950 stating that it was “a mad adventure that makes no sense…Puerto Rico could not exist as an independent state.”

He also said that the Nationalists were lunatics, fanatics and Communist dupes.

A few days later, the Times ran another piece on Nov. 6 stating that “there are 200 to 250 card-carrying Communists on the island…there is a hard-core of twenty to twenty-five. There is no official explanation why only seven of this latter group have been arrested.”

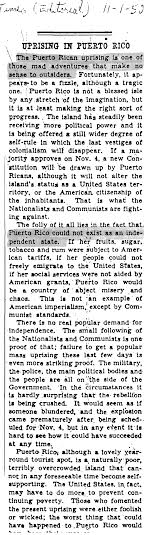

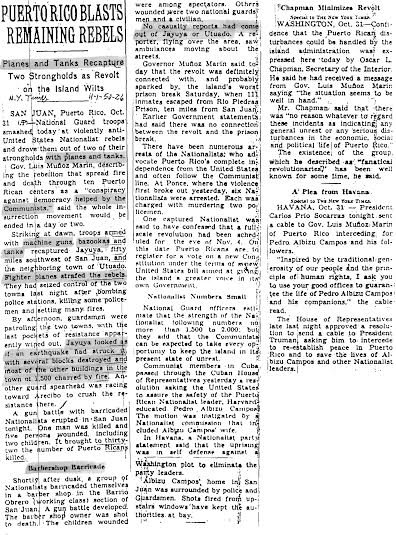

The military response was also immediate. 5,000 National Guard troops were deployed. 3,000 Puerto Ricans were arrested. Ten P-47 Thunderbird planes bombed Utuado and Jayuya, and the NY Times reported that fighter planes, tanks, machine guns and bazookas were used against the rebels. The Times also reported that Jayuya “looked as if an earthquake had struck it.”

El Imparcial reported it very bluntly: (Bombardeo)

In the long run, the revolutions on both islands solidified the U.S. government’s resolve to maintain control throughout Latin America.

The American public, which received most of its information through wire service reporters (AP and UPI) had no real grasp (and to be honest, not much interest) in what was occurring down below.

In Part II, we continue our discussion on Puerto Rican independence and the movement’s relationship with Cuba. In Part III, we cover issues surrounding the U.S. Latino community.

Great interview! I bought the book on Amazon, waiting for it to arrive.

I don’t understand why your publisher won’t translate it?! This is the history of PR where the main language is Spanish. You must get them to translate it!

Every Puerto Rican should read this book. It should also be translated in Spanish.

Puerto Rico is indeed a rich port. Collectively and intellectually we must decide the status of our Island.

Enough! Put your brain hats on and Vote appropriately. Puerto Rico is in such turmoil, in every aspect.

Peace and prosperity to all my Borinquenos.