Editor’s Note: All photos from the author.

The deserted island rose above the sands of the waterless Kern River. Gone were the days when its inhabitants waded to the shores.

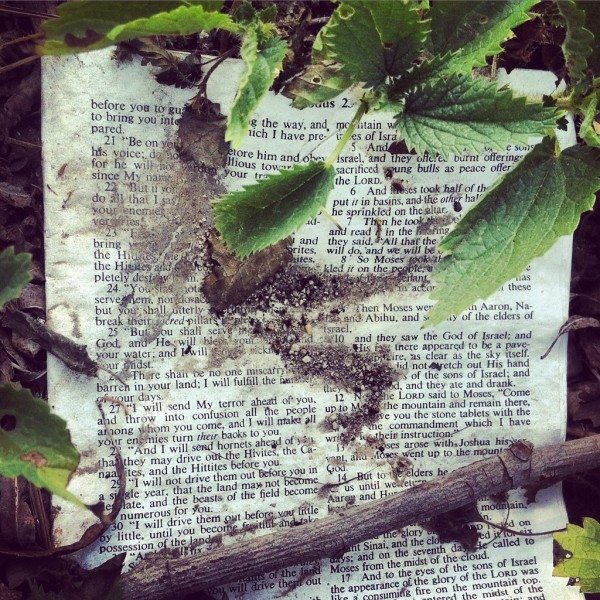

The island was now a wasteland. Among the trash of a destroyed homeless encampment lay a page ripped from a bible, half-covered in dirt and cottonwood leaves. Framed in muck, a verse from the Book of Exodus remained a disturbing omen, “I will send my terror ahead of you and throw into confusion all the people among whom you come, and I will make all your enemies turn their backs to you.”

A law enforcement sweep had come through—that was obvious. Some of the homeless had moved further down the drought-stricken river to hide among the dunes and trees. Others had gone to the cover of foliage across from the island. A sliver of path partially concealed with leafy branches led between a network of trees and bushes. Someone stirred behind the leaves. A small dog barked. This was the reality along the river where homeless slept between trees on small swaths of sand and dirt, some areas dug in to hide from the eyes of police, deputies, hikers or even other homeless.

The island was a different story.

Not a soul could be seen or heard. A pair of jeans lay like someone had been burned out of them. In a ravine was the bible page and a collection of broken memories: smashed styrene cups, spoiled jugs of milk, bottles, unused medicine, crushed strollers and disassembled tents, blankets, shoes, buckets, rusted cans, piles of clothes, broken plastic spoons and a lone paper heart.

The landscape was covered with foxtails and worn paths. Cottonwoods grew in tangles. Trunks lay against the ground as if some had fallen asleep to hibernate or die in this long drought. A lone palm poked above a tangle of weeds and grassy hills as if it could barely stand. Still, it seemed the sentinel of the island.

Sam Lynn Ballpark, one of the worst stadiums in America because of how it faces west into the sun was within sight of the island and the weir—all of it accessible to transients because no water flowed through here.

I’d come on my own sort of Exodus because of a character in my novel who lived on a fictitious version of the island that was surrounded by water. I’d read news articles about an invalid named Janice, seen video of her crippled in a tent before the fire had swept through part of the island. A horse owner told me about a man who raised miniature horses and goats though I saw no corral ruins here.

The child narrator of the novel is Sugarfoot, whose sister falls prey to human trafficking. Since I’d written about the island as his home, I wanted to go there, to finally see this place with his eyes.

Some nights coyotes stand on the edge of the mainland and howl at the island. Their grey fur stands on end. They growl and bark and yip. I’ve shined a flashlight into their eyes, seen their anger; watched them snarl and cry all over again. Mary of the Andes says there was once Natives here on our strip of forest. They stole spirits from coyotes and wolves long ago by wearin’ their blood. Says those men wore the spirits in smoke, which clung to them like fog in both winter and summer. Says animal spirits gave the people life, helped them live long in an unnatural world of struggle, where even peaceful men fall and break their necks, or get stabbed in the gut with sharp, pointed rocks, like the ones that pierced the hides of wooly mammoths and ancient cats. Says there was constellations that only the natives clothed in animal spirits could see. I never understood why them coyotes stood across the river and howled. Not until now. I promise, alive or dead, I’ll wear this blood and see you, Tender. I’ll see you again, I say, over and over, and cry myself to sleep in the bloody light of day.

The path to the island was along the northern banks on a strip of dirt that hadn’t seen water since the last brief rain. You had to cross the weir to get to the strip of dirt islanders trudged down to wade to the far shores, where they once floated everything they owned across in tubs. Water normally flowed through the weir, diverged into two other canals and a riverbed. Not now. One of the canals had a dry bank of shopping carts frozen in a waterfall of plastic and metal. Tumbleweeds hugged the pipes that once emptied water into a chasm where homeless strung lines for catfish and perch. Along a canal wall opposite was a message for the homeless: “Fuck tweekers.” Had the drought been the fault of the downtrodden?

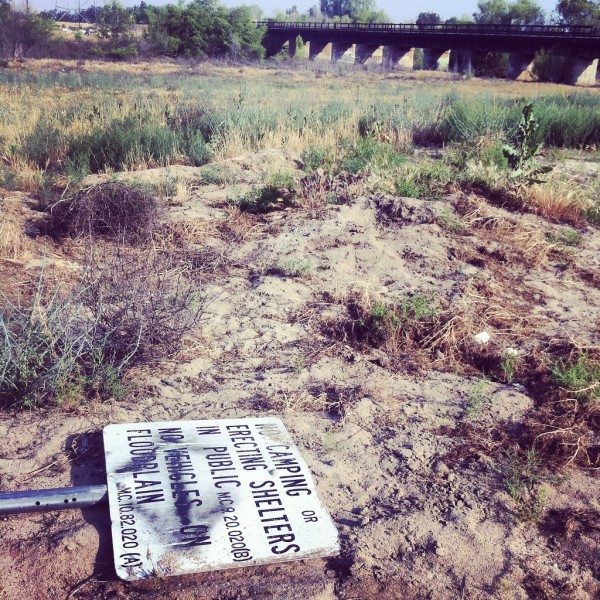

Another message was just as stark. Someone had spray-painted out part of a warning so that instead of “Stay Out, Stay Alive” on a fence above the weir, it just read STAY ALIVE. Surviving was hard enough around here. Surviving the law enforcement sweeps, the addiction, the foodlessness in this food desert, although its waters had been diverged miles from here, where twenty-five percent of America’s food was grown on the valley’s hundreds of miles of rich topsoil.

Close by was an overturned cart and two addicts who were oblivious to each other. One dug in the dirt along a curb. The other’s arms moved in herky-jerky motions as if he were break dancing and karate chopping the air all at once.

All the trash beneath the cart had been set on fire. The bottom of the cart was scarred as if meat had been cooked atop its metal grate. A half-burnt bingo card lay close.

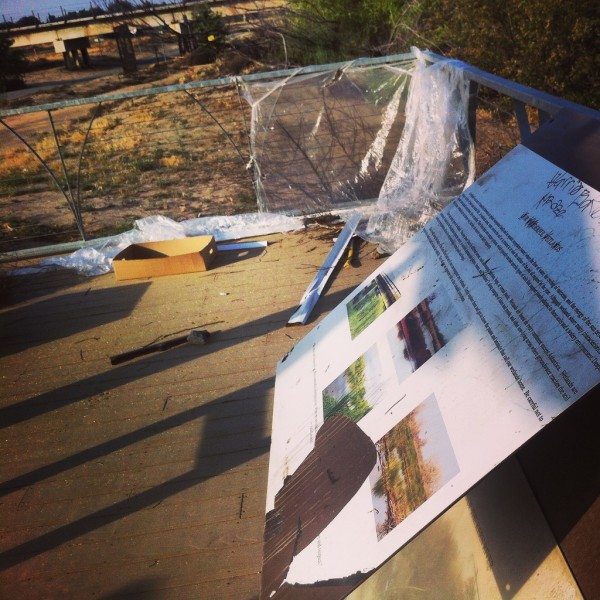

The last I’d seen the island, river water surrounded this place that government officials labeled Uplands of the Kern River Parkway, a marketing scheme to develop some of the riverfront with shoddy kiosks and stairways to nowhere within the dirt. The project, only a few years old, appeared ancient in this landscape devoid of water. One kiosk was strung with plastic that some homeless placed to block the dusty wind. The kiosk itself was broken from the heat, from warped wood left untreated in the elements. Even some of the signs had been constructed of metal waste cut at odd angles.

Two men in a city truck passed along the dry river’s recreational path, ignoring the trashed kiosk.

A pair in multi-colored cycling gear on $5,000 road bikes passed. Neither batted an eye at the countryside or the trash. Were they numb to this world? Maybe they were numb to America, or Bakersfield, in the same manner novelist Ben Fountain said his character Billy Lynn realized he was in the “middle of this very surreal, overamped artificial reality.”

Perhaps the cyclists’ reality spun around money, advertising and self-help fueled, supercharged workouts—middle class lifestyles where a recreational path was just a treadmill, a video game.

In the dirt it was obvious this kiosk area near the island had become of place of gay trysts, part of the hidden history of Bakersfield where British minstrels led hidden gay lives in the 1880s, and murderous and decadence-starved lawmen, judges, pastors, newspaper men have lived ever since, hiding a duality, hiding their secret rendezvous with other men and boys down by the river. Evidence lay in rubber gloves, lubricant containers, alcohol wipes sitting in the open.

A newspaper editor from the Los Angeles Times asked me the day I walked on the island, “When you see Bakersfield, do you see beauty too? Contrasting to the things you hate to see? Something that gives you hope?”

Since finishing the novel, Big Spoon, Little Spoon, I’ve often thought about Sugarfoot. What a beautiful kid. He loves his sister. He just wants a better life for the both of them.

“I think the beauty of the area is the valley itself, its grasslands, rivers, trails,” I replied. “This city has little beauty, though it does have character.”

I’ve seen kids like Sugarfoot. I know they exist. They’re surviving, staying alive, fighting for tomorrow as they run outside the baseball stadium hoping to catch a dream or just a ball they can maybe trade for a hot dog.

Another homeless encampment like the one on the island was being destroyed on Union Avenue in Bakersfield on Friday, April 10. The excuse from city officials? To destroy a wall and chain-link fence that the homeless obviously didn’t build, but was part of their collective shelter.

I consider any number of the people in Bakersfield as part of a creed of artificial reality, one with false ideals of some sort of boomtown farm and oil utopia that doesn’t exist. Wealthy or poor, many (though not all) dislike outsiders, especially lacking empathy for homeless, even though some have been on the same streets for many years.

I’m reminded of the Kern County Sheriff Donny Youngblood who recently said this to the LA Times: “I always say Kern is a county that ought to be in Arizona.”

His remark is truly a dig at people in the southern Central Valley, suggesting that Arizonans are superior in thought process and ideology, that there is perhaps misplaced patriotic anxiety within the rest of us in Kern County, that like former Vice President Dick Cheney’s criticism of President Barack Obama, that anyone who doesn’t side with the sheriff wants to “take America down.”

This place isn’t Arizona. Not the city or this dry island on an empty river starved by drought, strangled by farmers who use riverwater along with the oily wastewater sloshing through Bakersfield canals on their crops.

The people here will change. Give them ten years. The sheriff will be gone. The water will return. And the people, some of them who lived on islands and in encampments destroyed by law officials, will have found their hope.

“Sometimes we have to fall in love slowly,” I said to the editor about the places we’re from that we harshly criticize, though I think some never truly fall in love.

***

Nicholas Belardes is a writer, journalist and poet. He tweets from @NickBelardes.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.