Thirty-five years ago Rubén Berríos, the president of the Independence Party of Puerto Rico (PIP), made a very dramatic speech. He informed the world that both of the major parties in Puerto Rico were a complete fraud. The reason was very simple: both of them defined their candidates, and trolled for votes, and structured their party platforms on whether or not Puerto Rico should be the 51st state of the United States.

Berríos identified this as a complete sham because the Foraker Act (1900), the Jones-Shafroth Act (1920), the Puerto Rico Federal Relations Act (1950), Public Law 82-447 (1952), the U.S. Constitution (Article IV, Sec. 3.1), the U.S. Republican Party, Wall Street, the U.S. shipping industry and virtually all of corporate America were all opposed to statehood for Puerto Rico.

According to Berríos, the obstacles to statehood were so dense, that any political campaign based on the statehood issue (either for it, or against it) was an outright lie—since statehood was virtually impossible, and therefore a moot point.

Rubén Berríos was correct. The status issue is often used by people with no qualifications, political program or personal ethics, in order to get elected and put their entire family on the government payroll. This is part of the reason that Puerto Rico has a $73 billion public debt.

Instead of arguing endlessly about the status issue, the politicians and journalists in Puerto Rico should unite behind tangible, achievable goals. They should identify problems and offer solutions. Here are two problems and one solution:

PROBLEM #1: Puerto Rico’s Public Debt

The public debt of Puerto Rico is currently $73 billion. This debt is made worse because the three Wall Street rating services —Fitch, Moody’s, Dun & Bradstreet— all downgraded it to “Junk Bond” status within the past year. This means that Puerto Rico has been given the lowest possible credit rating: and therefore, the interest rate on this debt will be at the highest possible level.

This debt, and this high level of interest, is why the government of Puerto Rico has raised gasoline taxes in two years, raised the water and electrical rates, raised property and small business taxes, proposed a 16% VAT (value added tax, also known as IVA), and even proposed a “fat tax” on overweight children.

PROBLEM #2: The Cabotage Law

Under Section 27 of the U.S. Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (also known as the Jones-Shafroth Act), all goods carried by water between U.S. ports must be shipped on U.S. flag ships that are constructed in the U.S., owned by U.S. citizens and operated by U.S. citizens. That means that every product that enters or leaves Puerto Rico, other than highly taxed and severely regulated foreign registry vessels, must be carried on a U.S. ship to and from U.S. ports. That means that every product that enters or leaves Puerto Rico to U.S. ports must be carried on a U.S. ship—or face extremely protectionist quotas, tariffs, fees and taxes that are ultimately passed on to the Puerto Rican consumer. (In contrast, a 2013 GOA study speaks to how complicated the issue is.)

SEC. 27. JONES ACT – TRANSPORTATION OF MERCHANDISE BETWEEN POINTS IN UNITED STATES IN OTHER

THAN DOMESTIC BUILT OR REBUILT AND DOCUMENTED VESSELS; INCINERATION OF HAZARDOUS WASTE

AT SEA (46 App. U.S.C. 883 (2002)).6 No merchandise, including merchandise owned by the United States

Government, a State (as defined in section 2101 of title 46, United States Code), or a subdivision of a State, shall be transported by water, or by land and water, on penalty of forfeiture of the merchandise (or a monetary amount up to the value thereof as determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, or the actual cost of the transportation, whichever is greater, to be recovered from any consignor, seller, owner, importer, consignee, agent, or other person or persons so transporting or causing said merchandise to be transported), between points in the United States, including Districts, Territories, and possessions thereof embraced within the coastwise laws, either directly or via a foreign port, or for any part of the transportation, in any other vessel than a vessel built in and documented under the laws of the United States and owned by persons who are citizens of the United States,7 or vessels to which the privilege of engaging in the coastwise trade is extended by sections 18 or 22 of this Act: Provided, That no vessel of more than 200 gross tons (as measured under chapter 143 of title 46, United States Code) having at any time acquired the lawful right to engage in the coastwise trade, either by virtue of having been built in, or documented under the laws of the United States, and later sold foreign in whole or in part, or placed under foreign registry, shall hereafter acquire the right to engage in the coastwise trade: Provided further, That no vessel which has acquired the lawful right to engage in the coastwise trade, by virtue of having been built in or documented under the laws of the United States, and which has later been rebuilt, shall have the right thereafter to engage in the coastwise trade, unless the entire rebuilding, including the construction of any major components of the hull or superstructure of the vessel, is effected within the United States, its Territories (not including trust territories), or its possessions…

This includes cars from Europe and Japan, food from South and Central America, medicine from Canada—any product from anywhere. In order to comply with the Jones Act, all this merchandise must be off-loaded from the original carrier, reloaded onto a U.S. ship and then delivered to Puerto Rico. It all makes as much sense, as digging a hole and filling it up again.

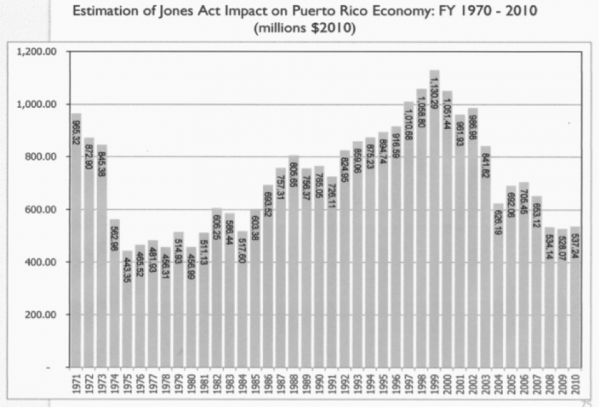

This is not a business model. It is a shakedown. It’s the maritime version of the “protection” racket. A 40-year study of this “cabotage cost” to Puerto Rico shows the following figures:

From 1970 through 2010, the Jones Act cost Puerto Rico $29 billion. Projected from 1920 up to the present, this cost becomes $75.8 billion.

Ironically, this $75.8 billion cost is higher than the amount of Puerto Rico’s current public debt, and a great portion of this public debt is owed to U.S. investment bankers, private equity firms and hedge funds.

SOLUTION: Problem #2 can solve Problem #1

The solution to these two problems is quite simple. Neither problem should have existed in the first place. But the two problems can now solve each other. Here is how that would happen:

- The U.S. acknowledges that the 1920 Merchant Marine Act was a dysfunctional and harmful piece of legislation.

- The U.S. Congress rescinds the 1920 Merchant Marine Act.

- Since the 1920 Act was harmful and unjust, the U.S. reimburses Puerto Rico for the adjusted net revenue losses from 95 years of this Cabotage law.

- The amount of this reimbursement (nearly $76 billion) will completely offset the public debt of Puerto Rico ($73 billion).

In one fell swoop, this will eliminate one of the principal vestiges of the colonial relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico.

It will also eliminate Puerto Rico’s public debt, and put the entire island on a firm financial footing.

It will eliminate a recurring hole in the island’s budget, which often reaches as high as $1 billion annually.

It will restore the island’s credit rating.

It will create an entire new industry in Puerto Rico: that of international shipping.

It will create many thousands of permanent jobs.

It is grounded in justice and common sense.

A Challenge to Both of Them

As Mercutio said just before dying in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, “A plague on both your houses!” He was referring to the Montagues and the Capulets, two families whose ridiculous and petty squabbles were causing many needless deaths, including his own.

These days, Governor Alejandro García Padilla (of the status quo PPD party) and Resident Commissioner Pedro Pierluisi (of the pro-statehood PNP party) are circulating petitions demanding each other’s impeachment. They criticize each other at every turn, and “position” themselves for the 2016 election cycle.

They “work” the federal government like a pair of high-priced lobbyists. The governor helps U.S. hedge fund managers to use Act 22 (with its 20-year interest, dividend and capital gains tax exemptions to foreign investors) to devour prime pieces of Puerto Rico real estate. The resident commissioner holds “Jones Act hearings” on giving specific shipping waivers to specific businessmen.

The message this sends to the U.S. government and journalists, is that Puerto Rico’s leadership is divided, disorganized and dripping with self-interest. No wonder the U.S. does not take our plebiscites, our protests, or even our people very seriously.

So here is a challenge to both the PPD and PNP: stop squabbling like children. Stop stuffing your pockets. Show a little discipline, and get united behind something important

We challenge you to stop acting like politicians, and be the leaders that Puerto Rico so desperately needs. The solution presented in this editorial is simple, sensible and solidly documented.

End the public debt of Puerto Rico. End the cabotage law. NOW!

Editor’s Note: Additional clarifications about the Jones Act were made.

***

Nelson A. Denis is a former New York State Assemblyman and author of the upcoming book, War Against All Puerto Ricans.

Oh the comments!

One of the biggest obstacles in ending this cabotage law nightmare is getting the maritime unions out of the way. It’s not in their economic interest to change the law and they are represented by some very powerful lobby groups on the Hill. The People of Puerto Rico from all political affiliations must ALL come together on this and force a change in the law or eliminate it altogether. It’s my understanding that the U.S. Virgin Islands are exempt from this law. It makes sense, they don’t create the enormous import and export activity that PR does. Undoubtedly a lucrative business for many, but on the other side of the “pond.”

Nelson, Orlando is right. As a fellow Latino Rebel I urge you to accept that what you wrote is just plain false, otherwise, your credibility will continue to erode. Take a trip do here and look at the flags of ships unloading shipments, and you will realize the truth. As a businessman in Puerto Rico who has actually received goods from countries other than the U.S., I know this for a fact. The Jones Act restrictions ONLY APPLY TO GOODS THAT ARE TRANSPORTED BETWEEN U.S. PORTS, INCLUDING ITS TERRITORIES. in other words, your assertion that all goods that enter Puerto Rico must be carried in U.S. flagged/crewed/built vessels is just plain false. The clarification that was issued does not make patently clear, leading the reader to easily conclude that all goods entering or leaving Puerto Rico have to be carried in U.S. vessels.

So for your own good and credibility, and to prevent a falsity to become a truth a la Hitler’s propaganda, please clarify this and accept that what you wrote is not correct.

BTW, I also believe that eliminating the Jones Act is good for PR, Hawaii, and Alaska, and that it will result in the improvement of the Puerto Rican economy, but the effect may not be as huge as most believe. The problem is that I think statehood has better chance of becoming a reality than a change or the repeal of the Jones Act, so you can imagine how low of a chance the latter has. You would have to overcome one of the biggest lobbies out there – the unions representing US Mariners and shipyards, which are extremely strong (unfortunately for us).

OmarP Omar, the additional language to resolve Orlando Gotay’s confusion was added…and for two days he continued to argue, as if the language had NOT been added.

He simply pretended it did not exist. Gotay was also notified, in my very FIRST reply to him, that the language (to resolve Gotay’s confusion – others were not confused) was being added. Again, he simply pretended that he had not read the reply.

There was thus no erosion…just an ongoing filibuster from Gotay, arguing into a vacuum.

Read the article…read my first reply to Gotay…and see for yourself.

Thank you for your interest and concern.

Unfortunately the edited version did nothing to rectify the following two false statements:

1) “That means that every product that enters or leaves Puerto Rico must be carried on a U.S. ship”. That’s incorrect.

2). “This includes cars from Europe and Japan, food from South and Central America, medicine from Canada—any product from anywhere. In order to comply with the Jones Act, all this merchandise must be off-loaded from the original carrier, reloaded onto a U.S. ship and then delivered to Puerto Rico. It all makes as much sense, as digging a hole and filling it up again.” This is also incorrect as long as it does not come from a U.S. port (and most goods from Europe, Japan, and South America come into PR straight from those regions, in non-US vessels.

As I’m hoping you realize, both of these are incorrect, false, and lead the readers to conclusions that are not true. The only restrictions the Jones Act imposes are on goods transports between U.S. ports, not between the U.S. and the rest of the world. So products come into Puerto Rico all the time ion non-US ships, in fact, 62% of the cargoes come into and out of PR in non US ships.

For whatever reason you refuse to acknowledge these facts, and some of us simply don’t understand why. I for sure I’m no fan of the Jones Act, but please let’s not distort the facts just to make a point.

Nelson Denis. Vuelvo al editorial y encuentro otras versiones de Orlando Gotay (OmarP) tratando de impugnar tu escrito.

A pesar de que añadiste una aclaración, a pesar de las intervenciones muy acertadas de Grace Vargas siguen insistiendo en la impugnación de tu escrito.

Se van por tecnicismos y olvidan lo más importante de tu escrito, los 29 billones que la Ley Jones le costó a Puerto Rico desde 1970 a 2010 y la proyección total de 75.8 billones desde 1920 al momento.

La tesis de que con ese dinero se puede pagar la deuda a ellos no les importa, especialmente a Orlando que defiende los intereses del monopolio naviero estadounidense que es el beneficiado directo de las Leyes de cabotaje.

Parece que tus editoriales y por supuesto el libro les está picando bien duro a los asimilistas.

OmarP

Unfortunately you missed the operative language that is in the article. Here it is below — bold, italicized, underlined. Thanks again for your interest in this subject.

Under http://www.upa.pdx.edu/IMS/currentprojects/TAHv3/Content/PDFs/Jones_Act_1920.pdf (also known as the Jones-Shafroth Act), all goods carried by water between U.S. ports must be shipped on U.S. flag ships that are constructed in the U.S., owned by U.S. citizens and operated by U.S. citizens. That means that every product that enters or leaves Puerto Rico, other than highly taxed and severely regulated foreign registry vessels, must be carried on a U.S. ship to and from U.S. ports. That means that every product that enters or leaves Puerto Rico to U.S. ports must be carried on a U.S. ship—or face extremely protectionist quotas, tariffs, fees and taxes that are ultimately passed on to the Puerto Rican consumer.

So if the Jones Act is repealed we would be left with only highly taxed and severely regulated foreign registry vessels carrying goods to and from PR?

OmarP That would not be a very great benefit.

The idea of Jones Act repeal would be to increase Puerto Rico’s control over it own coast, maritime activity, trade relations, and to generate an island-based shipping industry: ship building, operation, maintenance, and ownership.

This shipping industry would provide opportunities for many skilled laborers: carpenters, electricians, welders, electrical engineers, seamen.

The cabotage repeal could save the island government as much as $1 billion per year.

So both the private and public sector economies of Puerto Rico would be greatly improved.

Would this solve all of Puerto Rico’s economic problems? No – but it is a viable and achievable first step.

A step that does not invite foreign investors, US billionaires, and hedge fund operators, to buy up pieces of Puerto Rico.

In fact, it does the exact opposite:

It is a big step toward the building of a local, Puerto Rican economic infrastructure, that is not dependent on the US or another foreign power.

CarlosReyesAlonso

Asi es, Carlos.

Pero habiendo sido un Asambleista en NY, yo estoy muy bien acostumbrado a este tipo de intercambio.

A veces, hasta me divierte.

Kgsvega Yes..I think you see the problem…and the worthwhile goal.

nelsondenis248

After the interesting exchange between Mr. Denis and Mr. Gotay, let me add some humor, as a Sephardi-Jew…shall we change the old saying “2 Jews, 3 arguments” to “2 Boricuas, 3 arguments”? No offense intended. 😀

The word independent is offence in puerto rico? go ask the Hawaiian about they lost heritage

NicoEspinosa Seems to me in Puerto Rico you got bigger problems to worry about other than losing your heritage. How is your government planning on re-paying their 73 BILLION dollar debt? What a your solutions about that other “loosing your heritage”?

julio663md my solution is quite obvious, INDEPENDENT this way Puerto Rico could refinance it debt with the international community. as i understand it, because of it status, it NOT allow to refinance a debt, since this is the Federal government jobs, which Puerto Rico is not part of. there are trap into wanting to be part of the USA and speak Spanish

refinance the debt are financial matter only nation can do, Puerto Rico will get a better wall street rating to acomodate the debt, is not an easy process but you cant make an omelette without braking some eggs. bytheway i am not Puerto Rican i am just an spectator from across the Mona passage. i would rather see Puerto Rico as an independent nation but that is up to Puerto Rican to decide it future

NicoEspinosa julio663md Indeed, it is up to the people of Puerto Rico to decide, we do agree in that.

NicoEspinosa julio663md Yes, ideed, the people of Puerto Rcio have to decide. We do agree on that matter.

satamusic Supongamos por un momento que lo que propone Ruben Berrios se logre, y ya sea de la forma que el propone, o de cualquier otra logremos liquidar la deuda de PR. Eso seria muy bueno, fenomenal, motivo de mucha alegria y jubilo… Y despues… QUE???? Como se manejaria el dinero publico de PR de ahi en adelante??? Permitiriamos que los politicos sigan teniendo la potestad sobre el dinero del Pais??? Precisamente ESE es el FACTOR nos ha traido a la ruina!!! Los politicos hasta el presente han tenido el poder de usar el $$$ de PR y no nos debiera sorprender que haya pasado lo que esta pasando… Recordemos el viejo dicho: “la ocacion hace al ladron”. Ahora PR estaria solvente y que pasaria??? A cojer Prestado de Nuevo???? y a hacer party de nuevo??? Si se lo permitimos, lo haran nuevamente. De seguro cojerian prestado y en unos años estaremos de nuevo donde nos encontramos ahora mismo. El $$$ NO se le puede dejar en las manos nuevamente a los que lo han malversado, malbaratado, robado, o lo que sea. Nunca Mas!!!! Si hay algo que aprender de este bochornoso evento, es eso: El dinero del Pais no lo puede administrar ningun politico. Hay que buscar o idear una forma donde una Comision Ciudadana, o como se llame, controle el dinero de NOSOTROS. Alguna vez has pensado entregarle tu dinero a un vecino, o algun amigo o peor aun, a algun politico para que el lo administre???

Que tu crees que pasaria??? Pues, porque estamos haciendo eso ahora mismo, permitiendole al gobierno administrar NUESTRO dinero??? Miren los resultados!!! Hay que crear un sistema donde sea el pueblo, los que administremos el dinero del pais. Un grupo de Contadores, o como sea, que le respondan a la Ciudadania, no a los politicos. No se como lograrlo. Pero se que se puede. Donde Todas las Finanzas se vean en internet, o algo asi. Ya hay paises que lo estan haciendo, y Funciona!!! Recuerda Puertorriqueño: El Cabro no puede ser el que cuide la lechuga… se la va a comer… Siempre, siempre siempre. No es cuestion de “si se puede” , es cuestion de que si salimos de esto, y hacemos lo mismo de nuevo….wow…

Si despues que salgamos de esto, volvemos a dejar que los politicos manejen nuestro $$$ seriamos bien estupidos.

El $$$ de PR lo tiene que manejar la Ciudadania mediante algun mecanismo. Un grupo que le responda a la Ciudadania no a ningun partido o a ningun politico o al gobierno. Si los politicos tienen el control del $$$ SIEMPRE va a volver a suceder lo que esta pasando ahora. Que vamos a hacer cuando salgamos de esto??? Dejar que los politicos sigan manejando las finanzas??? Helloooooooo!!!!!!!!!!

Unfortunately, we speak very loud, but our island is too small for that, and to add, our younger generation is not available to attain or even maintain a state of independence.

NicoEspinosa julio663md Please let us be realistic, who in the world would refinance Puerto Rican debt? I am curious to see, without the backing of the US government and the US $ who would actually refinance this nascent nation?

nelsondenis248 OmarP The Foreign vessels you talk about are no higher taxed or no more regulated than vessels coming into US shores. It is actually cheaper to get a container from China than LA.

So what is your point? You make it seem like these vessels are expensive and regulated to somehow punish Puerto Rican people which is simply not true.

Juan Bergera NicoEspinosa julio663md Realistic? I am glad you raised that issue. On the same token, since you mentioned that issue of ‘without the backing of the US government the US $ who would actually refinance this nascent nation” you already noticed the the US, Congress and the Oval Office included DO NOT want to touch the financial crisis beyond “technical expertise” in other words, they don’ wan to touch it not even with a flagpole. Glad you brought that up, and I am sure you were just amusing us with your comment. Anything else besides the typical “Puerto Rico cannot exist without the US? (Whom obviously don’t give a flying flip about Puerto Rico) ???

FidelVazquez

You definitely should stop using your first name, use Candido instead.

FidelVazquez Fiji is small, compared to that PR is a continent

Juan Bergera NicoEspinosa julio663md i believe that this is definitely not the 1950, there are many other player out there not just the USA

NicoEspinosa Juan Bergera julio663md I am not disputing that there are more players than the USA, and definitely is not 1950. The problem with your argument is you first have to solve the colonial status before bringing in the other players you mentioned. As a reminder, the current situation with P.R. is that technically is that it is subject to U.S. Congress under the Territorial Clause of the U.S. Constitution, no more than a 100 x 35 mile property. Get rid of that condition, and then we can talk about other players.

I think we can #Younger_Generation_speaking don’t give up on all were learning and ready for ✊

[…] will do nothing about Jones Act reform, Chapter 9 bankruptcy relief, privatization of the island’s public schools, or the hedge funds […]

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.

[…] has been said of the economic crisis —whether in Puerto Rico, Greece or Spain— as if they were isolated and with different cases. Several institutions are […]