Editor’s Note: Earlier this afternoon, regular Latino Rebels contributor Roberto Lovato wrote this story from El Salvador. He emailed it to us for publication. All the photos in this piece are Roberto’s.

Greetings from El Salvador, land of the soon-to-be sainted Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero. I’m here as a journalist covering Romero’s formal beatification ceremony and celebrations tomorrow, although many people here will remind you, “We, the people, made him a santo long before the Church caught up.”

Thirty-five years after assassins killed Archbishop Romero as he preached on the need to build a “new family” in El Salvador, the country remains divided. But on the eve of his historic beatification, Romero’s message challenges and inspires that family as never before.

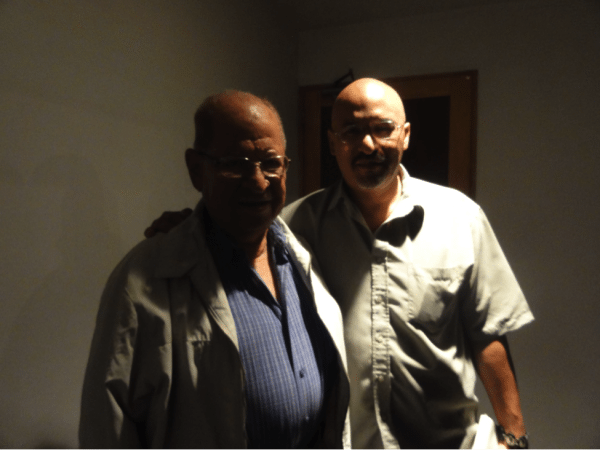

So our brief story about events here in contemporary El Salvador must begin with his family, specifically his brother Gaspar, one of the Archbishop’s two living relatives. Like many here, the younger Romero has, he says, worked to “bring my brother the recognition he deserves.” He’ll also be celebrating tomorrow’s beatification “with tears.”

Gaspar hopes that at least some of his brother’s and his family’s spirit can help cut through El Salvador’s intractable conflicts. To look him in the eyes and hear him speak in cadences reminiscent of his brother was to feel the family roots of that inform Romero’s greatness: “If we remember that to his last day, my brother believed in God and in God’s calling us to unite in love for the poor, the marginalized and the forgotten, he will be a happy saint.”

Gaspar also told me that his brother “could never support the deployment of the military to fight the gangs.” He was referring to the deployment of special, rapid response military units that were supposed to be taken out of rural and urban Salvadoran life as part of the peace accords signed in 1992.

“No,” said Don Gaspar with that soft dignity and slight lilt you can hear in his brother’s voice. “He wouldn’t agree with that.” On this central but indelicate point of Salvadoran life, the Monseñor and 80-year-old Don Gaspar agree with the twentysomething “Santiago.”

“We have killed and hurt many people,” admitted Santiago (name changed at his request), one of the few designated to speak officially on behalf of the 18th Street and Mara Salvatrucha gangs that, along with the security forces, are responsible for the lion’s share of El Salvador’s violence. “But ARENA [right wing opposition party] and the FMLN [left wing government party] have both made things worse with Plan Mano Dura and then Super Plan Mano Dura [hard-line gang suppression strategies], and they were and are as violent as we are.”

“La Selva” (the Jungle) neighborhood of Apulo, one the gang-controlled areas the author visited. As the author states in his email, “The Selva name runs dangerously close to feeding the multi-platformed Heart of Darkness psychosis at the heart of too much reporting on El Salvador.”

Like most Salvadorans, Santiago, who has been involved in gang truce negotiations rejected by both ARENA and the FMLN as excuses, also identifies with Romero and even bowed his head as he talked about the Archbishop: “He was criminalized, he was persecuted and he was exterminated by the government, like we are now.”

Continuing the family drama that brought us Romero’s sainthood, we move to the chapter involving the father of that contemporary culture of extermination of which the gangs (and some murderous security forces) are but the most recent expression.

“When I heard that Monseñor had been assassinated, I knew Roberto must’ve had something to do with it because of his connections to those [death squad] structures,” said Marisa Martínez, a leader of the Romero Foundation, which advocated for the Archbishop’s beatification and works to preserve his legacy and thought. Marisa is of a different branch than her older brother, Roberto d’Aubuisson, the man identified in a 1993 report by the United Nations Truth Commission as the person who “gave the order to assassinate the Archbishop.”

“I loved [Roberto] as a brother, but detested him as a military person,” Marisa told me in between beatification deliberations with her colleagues.

And our story ends where Romero’s begins: with El Salvador’s poor, its forgotten, its oppressed.

“Hey!” yelled the man in the official-looking beige vest, as María Lourdes Parada walked down the cathedral stairs to join hundreds celebrating mass in the crypt of Monseñor Óscar Arnulfo Romero, El Salvador’s martyred Archbishop and soon-to-be-saint.

“You have to take that off!” said the vested man, pointing at the camouflage-colored baseball cap with a big picture of Che Guevara on top.

“That’s not appropriate for the church,” he informed María Lourdes in an official tone indicating he had the authorization of the current Archbishop and other church authorities who were holding another more descafeinado mass in the air-conditioned main cathedral space upstairs, a mass largely devoid of Romero.

“You can’t order me around like that!” María Lourdes declared. “One of the compañeras in the comité Romero gave it to me because I have cancer and just got out of chemotherapy.”

“Look!” she added, removing her cap to show the man her shaven head.

After scrutinizing her head, he nodded and said, “Thank you, you can go down.” He then left.

“They’re like the orejas,” María Lourdes said, referring literally to the “ears,” a term used to describe the people spying for the government during the 12-year civil war that killed Romero and 80,000 others.

Before joining the festive mass of hundreds crammed into the humid hall of the crypt, María Lourdes, a labor psychologist, smiled and said, “These are the kinds of fear and intimidation tactics they’ve been using since before he died.”

And then, as if echoing Romero’s own, oft-quoted prediction —“If I am killed, I shall rise again in the Salvadoran people”— María Lourdes added, “but we have something they don’t: Romero’s combative spirituality!”

***

Roberto Lovato is a writer and a Visiting Scholar at UC Berkeley’s Center for Latino Policy Research. You can follow Roberto on Twitter @robvato.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.