The Ley de La Mordaza marked a notoriously dark chapter in Puerto Rico’s history. In force through much of the 1950s, Law 53 made it against the law to own a Puerto Rican flag, form a group, or write, state or hum anything that might be viewed as an affirmation of a separate Puerto Rican nationality.

It’s often forgotten that the law was passed a year after the U.S. government granted Puerto Ricans the right to elect their own governor, and by a Puerto Rican Senate headed by Luis Muñoz Marín, the same man who would eventually win the governorship. Many have suggested the gag law was a promise made by the insular quislings to their overseas overlords that, if Puerto Rico were allowed a tad more autonomy, its inhabitants would comport themselves as pliable, second-class U.S. citizens, and not as proud Puerto Ricans.

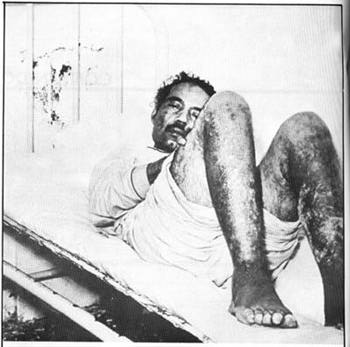

True to their word, the insular police sentenced the Nationalist poet Francisco Matos Paoli to 10 years imprisonment after raiding his home and finding a small flag that, while containing the correct colors, had far too few stars. His cellmate at La Princesa was Pedro Albizu Campos, the Nationalist leader whom the gag law sought to silence most, and who would soon be cooked alive by blasts of radiation.

The U.S. government having effectively destroyed the Nationalist Party, crippled the independence movement and driven militant separatists underground, and in the midst of a public-relations campaign meant to show the freedoms of democracies to be superior to the restrictions of communism, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled La Mordaza unconstitutional in 1957. (The federal and colonial governments would keep tabs on independentistas and their sympathizers, waging an unspoken war against Puerto Ricans that, with the extrajudicial killing of Filiberto Ojeda Ríos in 2003 and the continued imprisonment of Oscar López Rivera since 1981, seemingly persists to this day.)

Presumably, Resident Commissioner Pedro Pierluisi, the Partido Nuevo Progresista and others pushing for statehood remember the Ley de La Mordaza with as much grief and scorn as any jíbaro. And yet the status option they so long for is the same status that promises to accomplish what La Mordaza failed to.

A lot of statehooders disagree, reassuring their fellow islanders that Puerto Rico can become part of America without becoming American. The former speaker of Puerto Rico’s House of Representatives, José Aponte Hernández, writes in his pro-statehood op-ed last month that Puerto Ricans should “forget the silly arguments regarding the language and culture” because “Puerto Rico, as in the case of every state (Texas, Hawaii, Alaska, Nebraska, and so for) will maintain its own identity.”

First, though a lowly mainlander such as myself may not possess as firm a grasp on what it means to Puerto Rican as someone who was born, educated and has served on the island like Mr. Hernández has, the thought of comparing Nebraskan-ness to puertorriqueñidad should make anyone blush.

As for states home to large indigenous cultures, such as Hawaii and Alaska, I’ll leave it to him to ask the average Native Hawaiian or Inuit whether they were able to maintain their ancestral identities, cultures and traditions. The obstinate inhabitants of Molokaʻi, ironically nicknamed the “Friendly Island,” would say they’re doing their darndest.

To prop up his side, Hernández summons the old platitude that “America is a multicultural Nation since its very beginning.” Again, I would suggest he ask a black man living on the south side of Chicago or a Georgia Cherokee (if he can find one) just how multicultural America can be. Plus the people of Puerto Rico not only have their own culture—which after more than a century of efforts at Americanization remains mostly Spanish-speaking—Puerto Ricans also possess their own nationality: a Puerto Rican one.

Besides the immense sum Washington would have to pay merely to bring the island up to code—that is, on par with the poorest state in the Union—the United States is probably not too eager to bring into the fold a people who identify themselves as Americans legally but not culturally. Puerto Ricans see themselves as U.S. citizens and Puerto Rican nationals—or as the Partido Independentista Puertorriqueño leader Rubén Berríos put it in his 1997 essay on decolonization, “Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens, but they are not Americans.”

Driven by the false hope that the United States will welcome Puerto Rico as the 51st state someday soon, statehooders continue building political and economic bridges between San Juan and Washington. Those bridges, however, are bridges to nowhere. So long as Puerto Rico insists on remaining Puerto Rican, it will never receive a serious offer for statehood.

If the federal government’s century-long campaign of eradication against the Mohawk, Seneca, Seminole, Great Sioux, Cherokee, Creek and Apache nations teaches us anything, it’s that no nation, not even one with pretensions to multiculturalism like the United States, can or is even willing to be multinational. And what good is statehood, if Puerto Rico must lose its soul?

***

Hector Luis Alamo is a Chicago-based writer. You can connect with him @HectorLuisAlamo.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.