To Michael Brown & Ferguson

For Gabriella Naverez, a queer Black woman killed at 22 years old, unarmed

Pa’l Caribe y su diáspora; y para Delisa, con amor y escualidez (a lo Padura)

— “We will not forget.”

So read the cover of the New York Post Friday the 14th, three days after that unfortunate September 11, 2001. I still have the newspaper. It was certainly a tragic moment that shook the planet and, even more, those of us who witnessed it closely, marking us forever — violence, trauma, memories. My respect still goes to the families that lost someone that day and the brave rescuers who in the long days after gave all out.

However, I find it interesting, still, how the American nation every year prepares to commemorate el 11 de septiembre in order to achieve the goal that we never forget what happened. “Como son las cosas, compay,” read a verse of a song by Cortijo y su Combo, sung by the “Sonero Mayor” Ismael Rivera.

During the Sixties in Oakland, California Huey P. Newton, along with others —peace to Bobby Seale— established the Black Panthers, an African-American leftist movement that was organized to combat discrimination against Blacks, legitimizing violence and armed self-defense. Meanwhile, to the east, walking the streets of Montgomery, a young minister of the word of God, Martin Luther King Jr., marched peacefully talking about the right to vote, non-discrimination and other basic civil rights for Black folks in the United States. In the same decade, a resident of New York by the name of Malcolm X raised his voice in anger pointing out slavery’s long history but, above all, incriminating white Americans, particularly those who sat on their white-privilege, for being responsible for Blacks living in economic and social disadvantage. Freedom “by any means necessary,” he used to say.

Afro-Puerto Rican women in bomba dance wear (Spreadofknowledge)

Certainly African-American communities were expressing themselves for the violence experiences they had to live. But this was a Caribbean phenomenon as well. “Mami, ¿qué será lo que quiere el negro?” asked Wilfrido Vargas from the Dominican Republic. “Justicia pa los boricuas y los niche,” responded Ismael Quintana and Eddie Palmieri from New York. For Bob Marley and Peter Tosh in Jamaica it was a civil rights issue: “Stand up for your rights.” “Tite” thought, and Maelo sang, that it was also an issue of recognizing the immense value of “las caras lindas de mi raza negra.”

In short, both expressions, the Caribbean —in its broadest sense, including New York for example— intertwined with the African-American, shows a whole afro-transnational movement in search of respect and recognition, while trying to create its own memory: its “We will not forget.” Maybe that’s why following his death in 1970, some Afro communities from that Greater Caribbean sang a sabrosa guaracha from Cuban musician Arsenio Rodriguez that said:

Yo no soy Rodriguez

Yo no soy Travieso. Tal vez soy Lumumba

Tal vez soy Kasavubu

Yo nací del Africa

Sí, Africa

Soy el Congo, Tú eres mi tierra Mi tierra linda

Unfortunately, and all too often, these voices trying to create their own memory spaces are silenced. Criticism usually ranges from eso es de negros acomplejaos to ahí vienen las víctimas de nuevo, and everything in between. Why? Why are some memoirs privileged over others? Who determines that?

This cannot be taken lightly. With what moral is asked from Black communities to forget something that happened for over 400 years, and continues, but it is expected they remember what happened on September 11, 2001? And not only Afros (American or Latinos), but the entire world —pues con una propaganda multimillonaria— is supposed to remember the attack on the twin towers and all that it implied. But did the world stop on September 11, 2001, or is what happened —on that day or ever— the only thing the United States wants us to remember?

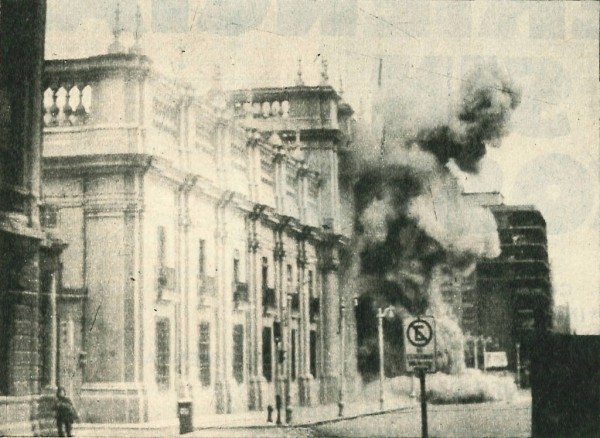

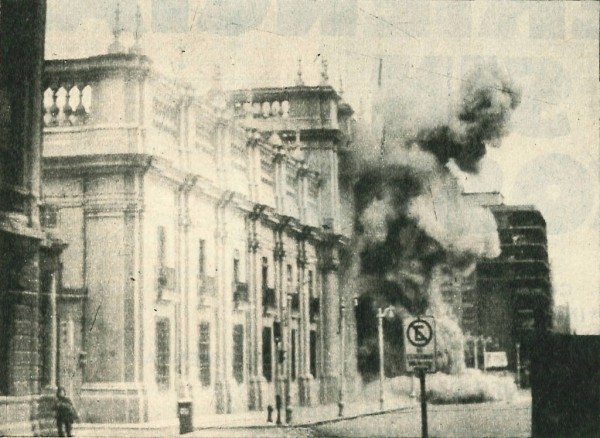

Bombing of La Moneda, Chile’s presidential palace, on September 11, 1973 (Library of the Chilean National Congress)

“Ya no se trata de memoria versus olvido, sino de memoria versus memoria.” – Elizabeth Jelin

I begin by mentioning what happened el 11 de septiembre de 1973. For some latinoamericanos this day already had a very deep meaning. It was the day that our sister nation Chile suffered a coup with the consent of the United States. Funded by Pepsi and ITT, it resulted in the unfortunate murder of the sitting president, Salvador Allende.

Moreover, by way of comparison, let’s observe only one event that happened in the world on September 11, 2001. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, that same day 35,615 children starved to death around the world, versus the less than three thousand deaths that occurred as a result of the attacks on the towers. How many commemorations were there on behalf of these children dying of hunger? Were there any special TV edition, press articles, manifestations of solidarity, moments of silence, social forums, messages from the Pope or the president or any alert levels raised? Was there any mobilization by the army or, better yet, some hypothesis about the identity of the criminals causing this much death in the world?

“La memoria intenta preservar el pasado sólo para que le sea útil al presente y a los tiempos venideros. Procuremos que la memoria colectiva sirva para la liberación de los hombres y no para su sometimiento.” – Jacques Le Goff

I’ve been interested in the works of the memory for a while now. Simón Rodríguez, a Venezuelan nineteenth-century thinker, said, “Abramos la historia; y por todo lo que aún no está escrito, lea cada uno en su memoria.” For his part, Bulgarian author Tzvatan Todorov on his book Los Abusos de la Memoria (English fuller version Hope & Memory) wrote that individuals and groups have the right to know, and therefore to know and make know their own history; it is not for the central government to forbid it.

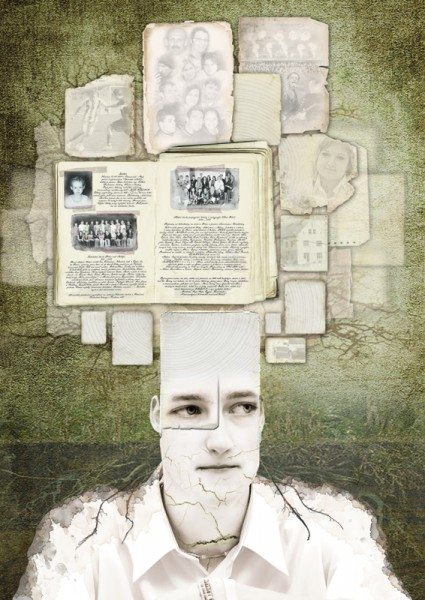

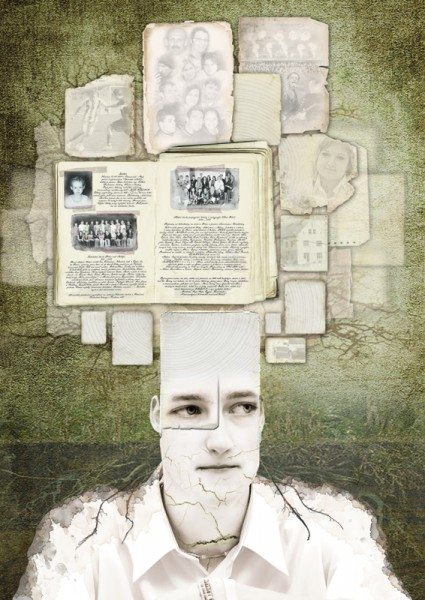

(Philip Bitnar/Flickr)

I totally agree with both authors, so much so that I’m embarking on a long-term project using some of my memories as valid contributions to historiography. But the central argument of Todorov’s work invites one to think carefully about memory studies, for their abuse lies precisely in the pain competition. Here I used several examples, including mine.

There is a literal memory —what occurred— and the obligation is to repeat the pain uncontrollably. It is a compulsive repetition of the event. This type of memory is known as intransitive: in constant loop. As a historian it leaves no room to work.

The issue here is between good and bad, between the oppressors and the oppressed. In the literal memory there’s a static identity, one that does not allow one to see in the other their humanity and the possibility that they have gone through some experiences, not similar maybe, but at least worthy of consideration. I am seeking a memory in which there is mourning. One that allows me the opportunity to work and develop other stories from violence, traumatized events like the ones I just described, that have in turn created a discourse, fixed images, of how one should remember them, marginalizing others memories.

El 11 de septiembre should be allowed many meanings. Thus, in the words of el maestro Rubén Baldes, “Usa la conciencia latino.” As for now, this day I’ll remember my cuñao‘s birthday; Big J, Jo-Jo, my man, Jonathan. Dios te bendiga mi hermano y que cumplas muchos más.

***

Rafael Acevedo-Cruz was born in Santurce, Puerto Rico and has lived in the tri-state area, Latin America and Puerto Rico. He has a B.A. in history from the University of Puerto Rico-Río Piedras where in 2013 began his graduate studies in history. His academic interests revolve around the cultural study of popular music and his work converses with the fields of recent history and memory studies. You can follow him on Twitter @racevedocruz.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.