As soon as the students left the teachers’ college at Ayotzinapa, their movements were being monitored — not by the local gang controlling the area, but by state and federal agents.

Since regaining control of the presidency in December 2012, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (under President Enrique Peña Nieto) had resumed its assault on leftist teachers’ groups opposed to the party’s social and economic policies, including a reform bill that would give the federal government greater authority over the nation’s education system.

In August 2013 a powerful teachers’ union — the Coordinadora Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación — began leading marches and rallies against the president and his proposals. They occupied government spaces and blocked main thoroughfares, which often ended in violent clashes with police. Among the protesters were students from Ayotzinapa.

After a year of protests, and at his wit’s end, President Peña Nieto was looking for a way to keep the activist teachers in check. At a meeting in August 2014, one of his advisors made a solemn promise: “Les vamos a partir la madre a los de la CNTE.”

By the time the Ayotzinapa students loaded onto two buses on September 26 and made their way to participate in another protest in Mexico City, they had been under state and federal surveillance along with Mexico’s other public enemies.

The students planned to stop in the nearby town of Iguala and commandeer three more buses, which they’d done in the past as part of something like a school tradition. The students got a hold of one bus and continued on to the bus terminal, where they took control of two more buses (and their drivers) and began to make their way out of town.

What the hapless students didn’t know is that one of the buses they took from the terminal was loaded with drugs, probably heroin. For years Mexico’s drug cartels had been using the town of Iguala as a waypoint for drug shipments headed northward to the United States. As in other places throughout Latin America, narcotraffickers often enlisted street gangs to act as deliverymen, and one can only imagine what members of the local gang Guerreros Unidos were thinking when they learned that one of their shipments had been hijacked by a group of students.

Not only were the students being pursued by federal agents and a local gang, the mayor of Iguala had ordered the students arrested for fear that they were in town to disturb a celebration being held for his wife. She was planning to succeed her husband as mayor, and it just so happened that her brother was a member of the Beltrán-Leyva Cartel, of which Guerreros Unidos was a subsidiary.

That means it very well might be that one of the buses carrying the Ayotzinapa students out of Iguala that fateful night in September 2014 also carried drugs being transported by the Guerreros Unidos for a cartel with close family ties to the mayor.

Fortunately for the gang members, the students were soon stopped by Iguala police officers who opened fire on the buses, killing 18-year-old Daniel Solís Gallardo and putting 20-year-old Aldo Gutiérrez Solano into a coma he has yet to awaken from. Most of the students were arrested, while others managed to escape and call their fellow students back in Ayotzinapa to tell them what had happened. Those students immediately left the school and traveled the 78 miles to Iguala to help their classmates.

Of the two buses that had sped away, one was stopped in front of the town’s palace of justice (of all places), while students in the other bus looked on from a nearby overpass. The second bus would also be stopped, but the students were allowed to continue on. Military officials would later admit to witnessing the attack on the bus near the palace of justice, though Mexican Attorney General Jesús Murillo Kaman would insist in a January press conference that military personnel were nowhere near any of the incidents on the night of September 26.

The second group of Ayotzinapa students arrived in Iguala at around 11 p.m. and met with the survivors of the earlier attack who had manage to escape. Together they returned to the scene of the shooting where the press had gathered to record eyewitness testimonies. As several students were speaking with reporters, a group of masked gunmen opened fire on the crowd, killing 23-year-old Julio César Ramírez Nava and 22-year-old Julio César Mondragón Fuentes, whose body was recovered the next morning with his eyes gouged out and the flesh on his face completely removed.

Elsewhere, on the outskirts of Iguala, a bus carrying the Avispones de Chilpancingo, a third-division soccer team on their way home from a match in Iguala, was mistaken for one of the students’ buses and fired on by police. A 15-year-old player was killed along with the bus driver and a woman riding in a taxi nearby.

The detained students were handed over to Cocula police in the wee hours of September 27, who then handed the students over to members of Guerreros Unidos. According to the government’s official report, the students were taken to a dump just outside Cocula. Fifteen students died of asphyxiation on the way. The rest were killed; their bodies destroyed in a fire that burned for 16 hours.

A report released earlier this month, however, throws doubt on the official story. According to experts assigned by the Organization of American States to study the disappearance, the suspects in custody who claim to have built the fire themselves could not have created a fire big enough or hot enough to burn 43 bodies in the amount of time that they say they did. Plus the smoke produced by such a fire would’ve been seen from miles away, even though there are no reports of anyone having seen a plume of smoke.

Nevertheless, in December the remains of 19-year-old Alexander Mora Venancio were identified by an Austrian forensic experts. The same team also identified the remains of 21-year-old Jhosivani Guerrero de la Cruz on September 16. The remains were found at the dump on the outskirts of Cocula.

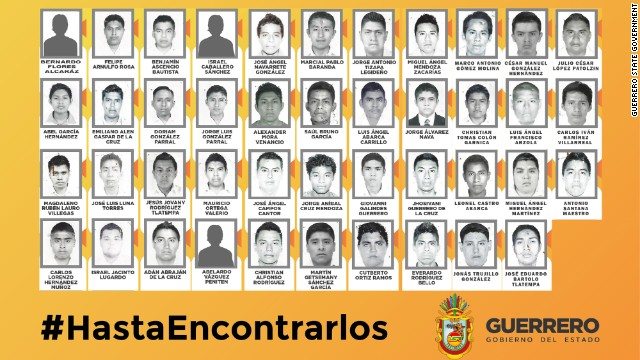

The names of those still missing are:

Abel García Hernández, 19 years old

Abelardo Vázquez Peniten, 19 years old

Adán Abrajan de la Cruz, 24 years old

Antonio Santana Maestro, 19 years old

Benjamín Ascencio Bautista, 19 years old

Bernardo Flores Alcaraz, 21 years old

Carlos Iván Ramírez Villarreal, 20 years old

Carlos Lorenzo Hernández Muñoz, 19 years old

César Manuel González Hernández, 19 years old

Christian Alfonso Rodríguez Telumbre, 21 years old

Christian Tomas Colón Garnica, 18 years old

Cutberto Ortiz Ramos, 22 years old

Doriam González Parral, 19 years old

Emiliano Alen Gaspar de la Cruz, 23 years old

Everardo Rodríguez Bello, 21 years old

Felipe Arnulfo Rosa, 20 years old

Giovanni Galindes Guerrero, 20 years old

Israel Caballero Sánchez, 21 years old

Israel Jacinto Lugardo, 19 years old

Jesús Jovany Rodríguez Tlatempa, 21 years old

Jonas Trujillo González, 20 years old

Jorge Álvarez Nava, 19 years old

Jorge Aníbal Cruz Mendoza, 19 years old

Jorge Antonio Tizapa Lecideño, 19 years old

Jorge Luis González Parral, 21 years old

José Ángel Campos Cantor, 33 years old

José Ángel Navarrete González, 18 years old

José Eduardo Bartolo Tlatempa, 17 years old

José Luís Luna Torres, 20 years old

Julio César López Patolzin, 25 years old

Leonel Castro Abarca, 18 years old

Luis Ángel Abarca Carrillo, 18 years old

Luis Ángel Francisco Arzola, 20 years old

Magdaleno Rubén Lauro Villegas, 19 years old

Marcial Pablo Baranda, 20 years old

Marco Antonio Gómez Molina, 20 years old

Martín Getsemany Sánchez García, 20 years old

Mauricio Ortega Valerio, 18 years old

Miguel Ángel Hernández Martínez, 27 years old

Miguel Ángel Mendoza Zacarías, 23 years

Saúl Bruno García, 18 years old

The heartbreaking and infuriating part of this whole story is that, while government officials were looking for clues as to what had become of the missing students, they uncovered 60 mass graves, revealing the fact that what happened on the night of September 26, 2014, in the town of Iguala happens more or less all the time across Mexico. At least 22,000 people have disappeared in Mexico during the past decade, close to 10,000 alone under President Peña Nieto’s watch.

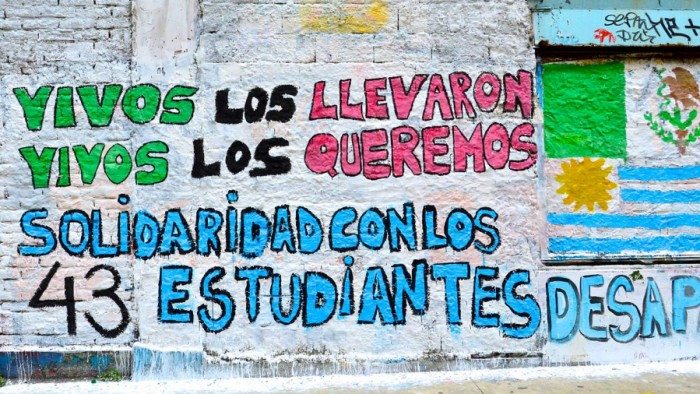

Thus, the missing 41 students have come to symbolize something else that has vanished without trace in Mexico: justice. Whether it can still be recovered, or whether its charred remains are buried in yet another mass grave somewhere out in the Mexican desert, only time will tell.

***

Hector Luis Alamo is a Chicago-based writer and the deputy editor at Latino Rebels. You can connect with him @HectorLuisAlamo.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.