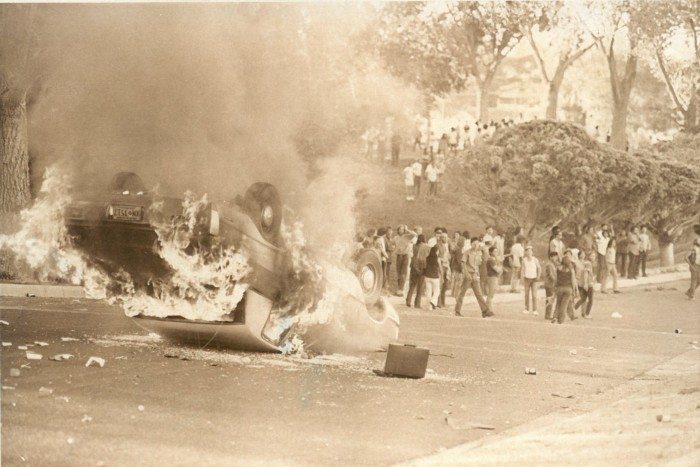

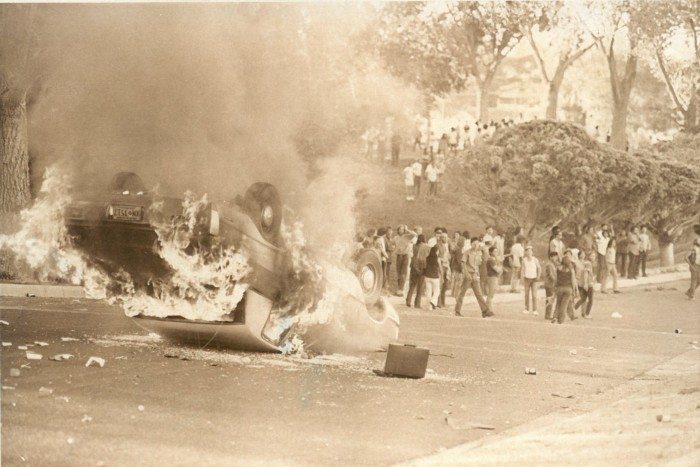

Rioting at Roosevelt Park in Albuquerque, New Mexico, June 1971 (Guy Bralley/Albuquerque Journal)

On June 13, 1971, rioting broke out at Roosevelt Park after police attempted to arrest a young man standing in a crowd of several hundred rowdy youth. A small scuffle escalated into a brawl leading officers to fire upon the crowd, wounding at least nine people. Outraged, nearly 500 youth moved into the downtown area where they overturned cars, shattered windows, looted, and severely damaged and destroyed buildings. Police attacked rock- and bottle-throwing protesters with tear gas but were overwhelmed. The New Mexico National Guardsmen came into the city to assist officers. After two days of rioting, the city tallied over $3 million in damages. Shocked by the level of carnage, one journalist of the Albuquerque Journal wrote, “It was something you’d think couldn’t happen in Albuquerque, but it did.”

Unlike the riots in Watts in 1965 or Detroit in 1967, Albuquerque lacks the evocative label of 1960s urban uprising. The actors were primarily Mexican American, and the riot occurred in the summer of 1971. Despite these anomalous characteristics, the rebellion was one of at least 14 Latino urban riots that occurred that year.

This year marks the 45th and 50th anniversaries of at least 17 Latino urban riots. These incidents have happened at least 57 times since 1964, but they are remembered in isolation. Preserving this history is crucial because the issues that sparked them, such as municipal neglect, discrimination and poverty, still exist in many communities around the country. Sadly American political culture portrays Latinos as recent arrivals, which makes it appear that these issues are temporary. Failure to address persistent issues in the community might increase the likelihood of another urban uprising in the near future — a plausible claim considering the incident of social unrest in Anaheim, California in 2012.

Most Americans are unaware of Latino urban riots because they fall outside of the black-white binary. Despite numerous books and documentaries about the 1960s and ’70s, these riots are rarely, if ever, mentioned. Sociologist Gregg Lee Carter published the only comprehensive piece of scholarship about the topic where he listed 43 riots in Mexican-American and Puerto Rican communities between 1964 and 1971. Nevertheless, there are some shortcomings in the list: some of the riots were melees, he missed several incidents, and they continued well beyond 1971.

I have provided an updated version of Carter’s list with hopes that people will become more interested in recovering this history and learn from it. By looking at several online newspaper databases and the works of other scholars, I included 25 additional riots. I disregarded racial violence, school and prison settings, as well as eliminated several of the incidents in Carter’s list. To determine what constituted a riot, I factored in that the event had to have at least 100 participants, result in significant property damage (destroying and/or severely damaging vehicles and buildings), and trigger a police response. With the exception of Los Angeles in 1992, Latinos were the primary actors in these riots; however, there were several incidents were whites and Blacks participated in almost equal numbers. There were numerous other incidents of civil unrest, but because property damage was minimal I did not include them. This list is incomplete because not all newspapers are digitized. Additionally, there was a discrepancy in reporting when Blacks and Latinos both rioted because some journalists reported only on Black rioters.

A glance at this list reveals some unique characteristics. Unlike Black riots of the 1960s, Latino riots occurred mostly in the 1970s, and they continued well into the early 1990s. Over two-thirds of them were in Puerto Rican communities. They occurred in major cities and in communities as small as Coachella, California, which had about 9,000 residents in 1970. Rioting broke out mostly in the Northeast. New Jersey had the most with 17 incidents.

In February 1968, government officials signaled alarms of anger in the Latino community. The Select Commission on Civil Disorder reported that “the rising needs of the Spanish-speaking people are being neglected as we grapple with the more massive pressures from the Negro population.” Political and police officials apparently ignored this warning when they admitted to indifference. “For all intents and purposes—politically, economically, and socially—the Puerto Rican community has been invisible,” noted Greater Urban Coalition leader Gustav Heninburg after the 1974 riots in Newark, New Jersey. “Until Sunday [the riots], nobody had taken them seriously.” In many communities, it took a riot just for local officials to acknowledge the Latino community.

These riots varied in severity. Rioting in Oxnard, California in July 1971 lasted for nearly two hours with several buildings destroyed and damaged. But rioting in Camden, New Jersey in August 1971 lasted for four days with property damages estimated in the millions. Today, Oxnard doesn’t bear any of the scars of rioting, but Camden, on the other hand, lost its middle-class tax base and remains the poorest and one of the most dangerous city in the country.

Not all of these incidents were sparked by police violence. The three-day riot in Passaic, New Jersey in August 1969 began after the eviction of a Puerto Rican household of twelve. In other incidents, rioting occurred after a public gathering. The riots in Hartford, Connecticut in September 1969 allegedly began when a crowd stood outside the Hartford Times office building to protest the publication of an article where a fireman made disparaging comments about the Puerto Rican community. “They are pigs, that’s all pigs,” he said. “A bunch of them will be sitting around drinking beer and when one is finished… he just throws the bottle anywhere… They dump garbage out of their windows. They lived like pigs.” It’s unlikely for a newspapers to publish such comments today, but as long as disadvantaged communities suffer from economic, political, and social marginalization, mending police-community relations won’t be enough to avoid riots.

At least one riot exposed intra-Latino conflict. In December 1990, several hundreds of Puerto Rican youth in Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood went on a rampage after the acquittal of six officers who beat a drug dealer to death. Expressing Puerto Ricans’ perceived insignificance in the city, local resident Clemente Montalvo said, “We want the people to know that we exist.” Continuing, he said, “Cubans get everything; we get nothing. When the Cubans jump, they get what they want.” Nearly 26 years later, the myth of Latino sameness prevails in American political culture. The dominant issue of immigration and the common assumption that all Latinos are Mexican has rendered Puerto Ricans invisible.

Like most rebellions, the underlying issues of discrimination, municipal neglect, poverty, police harassment, poor housing, poor schools and unemployment were all factors. But unique to Latinos, many expressed frustrations that the black-white binary overshadowed problems in their communities. It took a riot in 1991 for Washington, D.C. political officials to acknowledge the sense of alienation in the Salvadoran community. This could occur in other cities that have always been defined by the black-white binary where local officials might struggle to incorporate Latinos into the political system.

Oddly, Latino urban riots never led to a national discourse about race relations. Nor did any right-wing dialogue emerge about a Latino underclass culture, which was the explanation for Black urban riots. This could be explained by the fact that most coverage of Latino riots reported them as isolated incidents. Whatever the case may be, the absence of any such dialogue shows that even rioting could not eliminate the black-white binary.

It was not until the 1992 Los Angeles riots that Americans acknowledged that race expanded beyond black and white. Images of Korean shop owners protecting their stores and whites, Blacks, Latinos and Asians rioting and looting revealed a complex picture of race in America. Yet this appears to have been forgotten after the unrest in Ferguson and Baltimore. Several memes and tweets circulated on social media claimed that Latinos and Asians have never rioted nor would they ever engage in such activities. These individuals attempted to juxtapose Latinos and Asians with Blacks as being less troublesome. Riot-shaming neglects the fact that identical outbreaks of violence have occurred in Latino communities and the reality that they could happen again.

There are numerous low-income and working-class Latino communities that sit on powder kegs, but they have been rendered invisible by the immigration debate. Public officials’ and commentators’ efforts to paint Latinos positively in the midst of anti-immigration sentiment has also lead to the neglect of these communities.

Major cities with long-established Latino communities such as Cleveland, Milwaukee and Detroit have seen an increase in concentrated poverty between 2000 and 2013. In Philadelphia, Latinos have the highest poverty rate — at 44 percent as of 2016 — and are located in the poorest congressional district in Pennsylvania. Even worse, local officials often ignore the population. During a 2015 roundtable discussion about police-community relations, Al Dia, a Philadelphia-based Latino newspaper, noted that out of “22 panelists there wasn’t a single Latino.” Their absence was striking considering the fact that the community has dealt with the issue of police brutality for decades.

The Northeast is filled with cities and towns were residents are severely disadvantaged. Since the 1970s, low-income Puerto Ricans along with some Dominicans and Blacks have left New York City and New Jersey for affordable housing and safer neighborhoods in other parts of New York as well as Pennsylvania and New England. Although they find what they were looking for, they also encounter a whole new set of challenges.

In Pennsylvania, these groups have settled in cities such as Allentown, Reading, Lancaster and York only to encounter high unemployment, overcrowding, slumlords, poor schools, and persistent poverty. They are segregated into deteriorating homes where their children contract high levels of lead poison. The Reading and Allentown school districts, which are 81 percent and 68 percent Latino, are the most fiscally disadvantaged school districts in the nation. In Allentown, students articulate these frustrations in the schools, which were plagued with violence last fall. Meanwhile, Allentown city officials have invested close to $1 billion into a downtown revitalization project, even though local residents feel that they are not reaping the benefits.

Another example is Rhode Island. Latinos are located in cities such as Central Falls, Providence, Pawtucket and Woonsocket. Statewide, Latinos have the highest poverty rate and are also overrepresented in the prison system — making up 12 percent of the state’s population, but 24 percent of the prison population. Once released, ex-felons are discriminated against in public housing and employment.

In October 2015, Pawtucket avoided a violent altercation after 200 students protested an incident of police brutality at Tolman High School. While standing outside city hall, the crowd became aggressive after someone smashed a car window. The students started spitting and threatening officers. Police responded with pepper spray. Luckily violence was avoided, but it served as a sign to local officials concerning boiling frustrations in the community.

Police-community relations remain tense in poor and working-class communities. From 2010 to 2014, the Houston Police Department has killed civilians at a higher rate than New York and Los Angeles. In fact, Houston police have killed more people than Los Angeles police despite having a smaller population. The vast majority of unarmed victims have been Black and Latino. As of today, there has been no prosecutions or significant discipline of an officer. San Francisco has had several incidents of police shooting unarmed Latino men. Many of these killings have occurred near or in the Mission District, a predominately working-class Latino community. Over the past several years the area has experienced rapid gentrification that has led to a 27 percent decrease of the Latino population between 2000 and 2013. Both of these cities pride themselves in their ethnic diversity and social tolerance, but this narrative hides an ugly history and grim reality.

The similarities between now and then are striking, which is why the history of Latino urban riots need to be preserved. Fortunately, some scholars are doing just that. Newark Public Library archivist Yesenia Lopez is archiving the history of over a dozen Puerto Rican riots in New Jersey. Graduate students are researching the history of the Camden, New Jersey and Pharr, Texas riots of 1971. Still, more needs to be done, because most of these riots risk falling into oblivion.

This history is important because it’s a reminder that the black-white binary is problematic. Continuing to see racial conflict this way not only renders Latinos as invisible, but also makes it appear that they are unaffected by the most pressing social justice issues of our times. This should also serve as a lesson for Latino political organizations and media outlets who generally focus primarily on immigration. Viewing Latinos as recent arrivals renders insignificant the experiences of those here prior to recent waves. It dehistoricizes social and economic issues within the community. Unless these issues are addressed, some communities might articulate these grievances in an unpleasant way.

| Latino Rioting in the United States | ||

| Location | Date riot began | Group |

| Chicago, IL | 6/12/1966 | Puerto Rican |

| Perth Amboy, NJ | 7/31/1966 | Puerto Rican |

| New York, NY | 7/23/1967 | Puerto Rican |

| New Haven, CT | 8/19/1967 | Puerto Rican |

| Paterson, NJ | 7/1/1968 | Puerto Rican |

| New York, NY | 7/19/1968 | Puerto Rican |

| New York, NY | 7/20/1968 | Puerto Rican |

| Trenton, NJ | 6/12/1969 | Puerto Rican |

| Passaic, NJ | 8/3/1969 | Puerto Rican |

| Hartford, CT | 8/10/1969 | Puerto Rican |

| Hartford, CT | 9/1/1969 | Puerto Rican |

| Chicago, IL | 9/13/1969 | Puerto Rican |

| Coachella, CA | 4/5/1970 | Mexican American |

| New York, NY | 5/12/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| Jersey City, NJ | 6/10/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| New York, NY | 6/14/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| Hoboken, NJ | 6/24/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| Los Angeles, CA | 7/3/1970 | Mexican American |

| New Brunswick, NJ | 7/24/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| West Chester, PA | 7/25/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| New York, NY | 7/25/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| Hartford, CT | 7/28/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| New Bedford, MA | 7/29/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| Jersey City, NJ | 8/9/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| Waterbury, CT | 8/15/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| Hoboken, NJ | 8/27/1970 | Puerto Rican |

| Los Angeles, CA | 8/29/1970 | Mexican American |

| Los Angeles, CA | 8/30/1970 | Mexican American |

| Los Angeles, CA | 9/16/1970 | Mexican American |

| Los Angeles, CA | 1/9/1971 | Mexican American |

| Los Angeles, CA | 1/31/1971 | Mexican American |

| Pharr, TX | 2/6/1971 | Mexican American |

| New York, NY | 5/17/1971 | Puerto Rican |

| Bridgeport, CT | 5/20/1971 | Puerto Rican |

| New York, NY | 6/9/1971 | Puerto Rican |

| Albuquerque, NM | 6/13/1971 | Hispanic |

| Oxnard, CA | 7/19/1971 | Mexican American |

| Parlier, CA | 7/26/1971 | Mexican American |

| New York, NY | 7/27/1971 | Puerto Rican |

| Waterbury, CT | 8/14/1971 | Puerto Rican |

| Lakewood, NJ | 8/17/1971 | Puerto Rican |

| Camden, NJ | 8/19/1971 | Puerto Rican |

| Hoboken, NJ | 9/4/1971 | Puerto Rican |

| Dover, NJ | 9/6/1971 | Puerto Rican |

| Union City, CA | 9/12/1971 | Mexican American |

| Paterson, NJ | 10/10/1971 | Puerto Rican |

| Ontario, CA | 1/16/1972 | Mexican American |

| Santa Paula, CA | 4/23/1972 | Mexican American |

| Placentia, CA | 6/18/1972 | Mexican American |

| Boston, MA | 7/16/1972 | Puerto Rican |

| Chelsea, MA | 9/6/1972 | Puerto Rican |

| Bridgeport, CT | 5/2/1973 | Puerto Rican |

| Warminster, PA | 5/13/1973 | Puerto Rican |

| Buffalo, NY | 6/23/1973 | Puerto Rican |

| New York, NY | 6/26/1973 | Puerto Rican |

| Dallas, TX | 7/28/1973 | Mexican American |

| Long Branch, NJ | 8/19/1973 | Puerto Rican |

| Camden, NJ | 8/29/1973 | Puerto Rican |

| Union City, CA | 4/29/1974 | Mexican American |

| Wilmington, DE | 4/30/1974 | Puerto Rican |

| Philadelphia, PA | 7/30/1974 | Puerto Rican |

| Newark, NJ | 9/1/1974 | Puerto Rican |

| Springfield, MA | 8/28/1975 | Puerto Rican |

| Wilmington, DE | 10/20/1975 | Puerto Rican |

| West Chester, PA | 7/11/1976 | Puerto Rican |

| Chicago, IL | 6/4/1977 | Puerto Rican |

| Bridgeport, CT | 7/7/1977 | Puerto Rican |

| New York, NY | 7/13/1977 | Puerto Rican |

| Houston, TX | 5/7/1978 | Mexican-American |

| Worcester, MA | 6/21/1979 | Puerto Rican |

| Meriden, CT | 8/29/1979 | Puerto Rican |

| Holyoke, MA | 8/13/1980 | Puerto Rican |

| Lawrence, MA | 8/9/1984 | Hispanic |

| Perth Amboy, NJ | 6/9/1988 | Hispanic |

| Philadelphia, PA | 9/27/1988 | Puerto Rican |

| Vineland, NJ | 8/28/1989 | Puerto Rican |

| Miami, FL | 12/3/1990 | Puerto Rican |

| Washington, DC | 5/5/1991 | Salvadorian |

| Los Angeles, CA | 4/29/1992 | Hispanic |

| Washington, DC | 5/10/1992 | Hispanic |

| New York, NY | 7/4/1992 | Dominican |

| New York, NY | 7/9/1993 | Dominican |

| Worcester, MA | 8/24/1993 | Puerto Rican |

| Syracuse, NY | 6/15/1995 | Puerto Rican |

| Los Angeles, CA | 7/29/1995 | Mexican American |

| Lancaster, PA | 9/24/2000 | Puerto Rican |

| Worcester, MA | 8/18/2002 | Puerto Rican |

| Los Angeles, CA | 9/6/2010 | Guatemalan |

| Anaheim, CA | 7/21/2012 | Hispanic |

CORRECTION, August 19, 2016: This article stated that the rioters were mostly Mexican-American, but some Americans of Spanish and Native descent in New Mexico also refer to themselves as Hispanic. Wire stories reported the event as a Mexican-American riot. Also, the nine people shot by police occurred during riots, not initially at Roosevelt Park.

***

Aaron G. Fountain, Jr. is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History at Indiana University-Bloomington. He tweets from @aaronfountainjr.

Interesting that Cubans and South Americans don’t appear on this list. hmm…