Donald Trump, real-estate mogul and GOP presidential candidate (Gage Skidmore/Flickr)

Latinos have been center stage during this election cycle. There is a rare news day when they are not mentioned. Huffington Post Global Editorial Director, Howard Fineman, has even called the 2016 election, the “Mexican-American election.” All this may indicate that this is the year that Latinos have taken their central role in the grand American political drama. For some, 2016 is the year that Latinos’ purchasing power and demographic growth has been realized as real political power and not just abstract potential.

But as much as Latinos are in the news, it is the Republicans who seem to be driving the conversation. While Latinos are becoming more central to Republican rhetoric and policies, Latinos are participating less in Republican politics. For decades, many influential strategists pinpointed Latinos as the key demographic for Republican’s future success. As recent as 2012, the Republican National Convention in its “Growth and Opportunity Report,” singled out Latinos as the key to future electoral victories. Since then, Donald Trump has effectively destroyed nearly 40 years of Latino outreach in a single year-long campaign. How can the chasm between how Latinos are being talked to and how they are being talked about in Republican politics be explained? To understand this divide, you must understand that this election is not about Latino outreach. Latinos are caught in an internal GOP civil war. The two warring factions are using Latinos as rhetorical phantoms, not real people, in their larger ideological battle for control of the party.

Trump’s triumphant primary victory and general-election flameout points to a growing divide in the Republican Party. The early political success of the party began in the 1970s with a coalition composed of socially conservative evangelicals, ideologically driven free-market economists and policy makers, foreign-policy hawks who wanted to win the Cold War, and racially anxious white workers. This mix proved to be a powerful formula, winning the White House for Republicans in 1980, 1984 and 1988. Their success even forced Democrats to dramatically change their policies, priorities, and politics in 1992, a change that has continued in the post-Bill Clinton era. This Republican coalition reached its highpoint in 2000 and 2004.

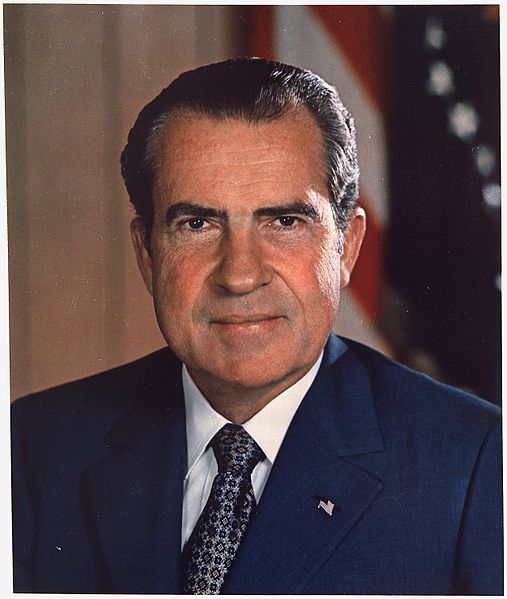

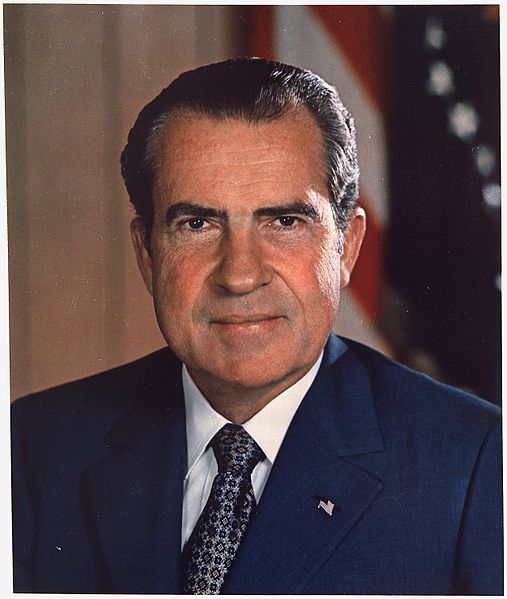

Since then, its electoral power has declined and its cohesiveness has come undone. Today, the Republican coalition that won five out of seven presidential elections between 1980 and 2004 has devolved into two disconnected wings. One is a rising but electorally stagnant far-right white nationalist wing composed of voters who believe that the nation’s identity and future is inarguably white. Non-whites are a threat: walls must be built to keep them out; deportation forces must be raised to ship them out; tests must be administered to insure proper ideological purity. Their presence in the party is not new. Richard Nixon courted the predecessors of these voters with his “Southern Strategy,” in the 1970s, but their influence has been on the rise since the 1990s and 2000s.

What began with English-Only movements grew into the Minutemen, a self-avowed force of citizen-patriots who saw it as their duty to protect the American body politic by policing borders and brown bodies. There were hints of their growing power in the party with the nomination of Sarah Palin as the vice president in 2008. She represented for many a truer, more authentic America. The Republican loss in 2008 ushered in the Tea Party with midterm elections in 2010. This group was ardently anti-government, wrapped itself in the imagery of the American Revolution to indicate that they, a predominantly white group, were the heirs of the true revolutionary tradition and American values. While Tea Party candidates have won various victories on the state level, they have also paralyzed the Republican Party’s ability to govern on the national level, most notably causing a government shutdown, the demise of the “Gang of Eight” immigration reform bill sponsored by Marco Rubio, the ousting House Speaker John Boehner, and even made Paul Ryan second guess his decision to accept the position.

The other wing of the party is a neoliberal one, composed of a small economic elite. It is the group that Occupy Wall Street came to call the “1percent” at the height of the Great Recession. Their influence is undeniable and they have been the leading force in the Republican Party since the 1970s. They oversaw the enactment of policies that included, deregulation, free-trade, and globalization. Beginning with deindustrialization in the 1970s, they created policies that would lower import tariffs that would make it cheaper to import goods into the U.S. This made it profitable to outsource manufacturing. At first, from the 1970s to early 1990s, it was in geographically small free trade zones along the U.S.-Mexico border. By the mid-1990s, experimentation with limited free trade zones took international shape with the rise of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994. With NAFTA, the entirety of North America would be a unified free trade zone. These limited zones grew into hemispheric and global dimensions with the rise of the World Trade Organization, CAFTA, and possibly the Transpacific Partnership (TPP). They oversaw the demise of the vertically integrated corporation that could be regulated and taxed, creating a new distended model that was broken into disconnected pieces across the globe. Each piece was treated as separate entity that had their own employees and owed very little taxes to anyone. The policies enacted by this wing disproportionately benefitted corporations and corporate leaders. They paid fewer taxes and were able to keep more of the profits. These policies also undermined wages across the globe and eroded the tax base of many liberal democracies. This group continued to link free trade with greater domestic freedoms. Mitt Romney represented the interests and political will of this group in 2012.

These groups were too small to win elections on their own. They needed to fill their ranks with supporters. For many decades, it was college educated whites. Republicans won this group from 1956 to 2012. Trump has eroded those numbers because of his explicitly racist positions. As FiveThirtyEight reported, Romney carried college-educated whites by 8 points in 2012. This year, some polls show Clinton with a 17 point advantage among that group. At the same time, the white electorate is declining. In 1980, the electorate was 88% white. When Romney lost in 2012, it was 72% white. The 2016 election will have the most diverse electorate in U.S. history. The shifting demographics in the nation and Obama’s clear victories forced the RNC to admit in their 2012 report that “America looks different.”

The Obama Coalition trounced the Republicans and it was primarily minority voters that provided them the electoral power. The Republicans believed that they could borrow a page from the Democrats’ playbook and in that effort they pinpointed “Hispanics.” Romney had received a paltry 27% of the Latino vote, a number which had been in decline since George W. Bush’s watershed outreach effort garnered 44%. The RNC planned to pivot on immigration reform, soften their anti-Mexican rhetoric, and promote Latinos in the party. They hired millennial Hispanic staffers and re-energized efforts like the Future Majority Project. For the RNC, composed primarily of the neoliberal wing of the party, these shifts in policy were, as the “Growth and Opportunity Report” stated, “consistent with republican economic policies that promote job growth and opportunity for all.”

For the small group that promoted globalized economic integration and a reduction in domestic social programs, the shift in rhetoric and immigration policy was indeed consistent with their beliefs. This group began to talk to Latinos again. People like former RNC Director of Hispanic Communications, Ruth Guerra, a 27-year-old bilingual millennial, gained influential positions in the party. The Koch brothers funded projects like the LIBRE Initiative, which promotes free market ideas to the Latino community. Executive Director Daniel Garza explained to journalists: “I’m willing to be demonized, to be called every name in the book, that I go against Latino interests, to prove that I’m not. [The] ideas that I believe in will lift Latinos.”

While this outreach made sense to the wing of the party that focused on free-market economic policies, it was completely antithetical to the other wing in the party. It was contradictory to their beliefs that the U.S. was a white nation whose policies should benefit white workers. This group started talking about Latinos again, with more divisive rhetoric. Far-right politicians compared Latinos to feral hogs and drug mules. Iowa representative Steve King, at the Republican National Convention, even questioned the idea that minorities had contributed to the history of western civilization, asking host Chris Hayes “go back through history and figure out where these contributions that have been made by these other categories that you’re talking about, where did any other subgroup of people contribute more to civilization.”

With Trump’s nomination the fraying strands of the Republican Party finally ripped. Trump showed that the small economic wing of the party had lost control of the party to the nationalist wing. While both were small, the nationalist wing had more power within the party even though the neoliberal economic wing had more sway outside of it. This was displayed by Trump’s victories over influential governors Jeb Bush, John Kasich and Chris Christie. Trump’s white nationalism wins Republican primaries, but it loses presidential elections.

The competition for power within the GOP is what has brought the discussion regarding Latinos to the forefront. Neither group wants to listen to the diverse communities within this specific electorate. They don’t want to hear their problems or offer solutions. These two warring factions want to construct straw men out of real people. They want to paint them as either good workers or evil drug traffickers—ignoring the fact that they area activists, lawyers, public school teachers, journalists, mothers, fathers and even citizens. This dichotomy between good and evil provides them justification to continue with their ideologically driven policy solutions. If they are workers, then, Latinos simply need lower taxes, more free trade, and less government. If they are drug traffickers, they need to be rounded up and deported, kept out, or possibly shot.

Either way, the two wings only want to talk about Latinos, not listen to them.

Latinos are in the crossfire of an internal GOP civil war. This election isn’t about the place of Latinos in the nation or their impacts on the nation. It’s about an internal ideological battle within the Republican Party. Latinos are a rhetorical phantom; they represent the future or the downfall for the two ideologically opposed wings of the party. For some, Latinos are the central target to be neutralized in this civil war. As Republican Governor of Maine Paul LePage said recently, “When you go to war, if you know the enemy[…]You shoot at the enemy[….]And the enemy right now, the overwhelming majority of people coming in are people of color or people of Hispanic origin.”

For others, Latinos have been collateral damage, victims in an explosion caused by a party in an ignorant act of self-immolation. As former Trump Hispanic Advisory Council member and Texas pastor Ramiro Peña told Politico after Trump’s touted immigration speech in Phoenix, Arizona “I believe Mr. Trump Lost the election tonight. The National Hispanic Advisory Council seems to be simply for optics and I do not have the time or energy for a scam.”

***

Aaron E. Sanchez received a Ph.D. in history from Southern Methodist University. You can connect with him @1stworldchicano.