GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump (Peter Stevens/Flickr)

The media’s coverage of the fear running rampant through undocumented immigrant communities has mostly focused on mass deportations if Donald Trump were to become President. While the fear of possibly being deported and the chaotic, unforeseen logistics surrounding an individual’s deportation are very much daunting and real, it does not stop there.

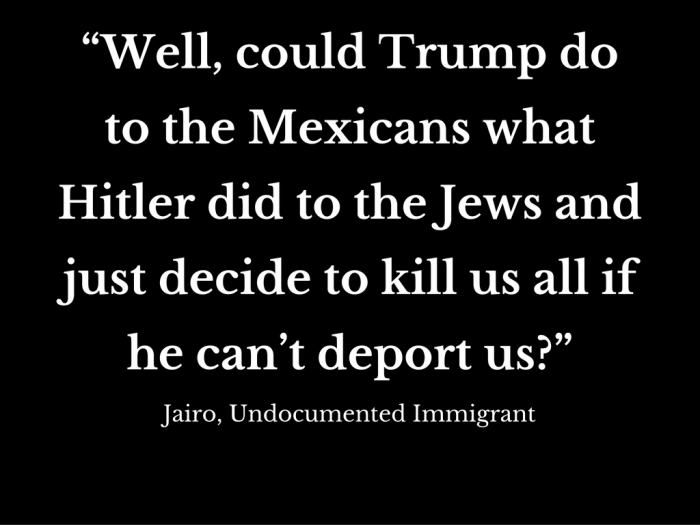

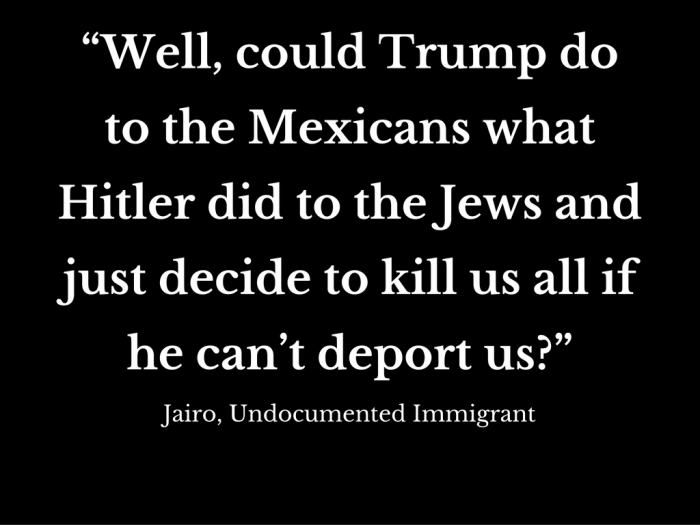

Last week I had a long, overdue talk with my friend Jairo, a long-time friend from Oaxaca, Mexico. He is undocumented, comes from an indigenous background and speaks the Mayan language of Chatino, in addition to both fluent Spanish and conversational English. Jairo was anxious to know what I thought of Trump, and he had many questions.

He wanted to know if Trump could really deport all of the undocumented Mexicans and Central Americans immediately and at the same time. I assured him that no, that could never happen. “The President can’t just order 11 million people to be removed from the country. That’s not how government works,” I explained to Jairo, and he understood.

“But what about what Hitler did to the Jews?” he asked back. I was completely dumbfounded. “Why is he talking about Hitler?” I thought to myself.

“What about it?” I asked.

Since Donald Trump begun his candidacy for President of the United States and won the Republican party’s nomination, the constant fear that looms over the lives of undocumented Latino immigrants and their communities has morphed into something more powerful than just fear and uncertainty—it has transformed into terror.

Trump’s original assertion that he planned to immediately deport the some 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States back to their home countries (especially Mexicans and Central Americans) have left members of the Latinx community, particularly the undocumented, with more imminent questions, concerns and apprehensions regarding their physical safety and their futures in this country than they have had in a very long time.

Jairo is not the only undocumented immigrant that I have spoken with who has expressed deep-seated fear and anxiety surrounding how his life could change, and what he would have to do if Trump were to become President. Others undocumented Latinx immigrants that I know personally have been asking more and more about Trump, too.

Manuel, a middle-aged man from Guatemala who, like Jairo, is indigenous and also speaks Mayan languages (although his Spanish is much more limited, and his English virtually non-existent) was also unsure of where the power of the President and the U.S. government lays, and to what extent it can be expressed.

Similarly to Jairo, Manuela is afraid that the U.S. government under Trump could basically do whatever it wants it to him or to anyone else, including ending someone’s life.

A survivor of the Guatemalan civil war, Manuel witnessed the Guatemalan army murder his parents and siblings before fleeing to the mountains to hide for 14 years. He revealed to me that not a single day goes by that he doesn’t think about the war and the genocide. As an undocumented immigrant and former genocide survivor with no formal legal protections from the law or the government, Manual never rules out the possibility of the worst events repeating themselves.

The oversaturation of information about Trump in the media, particularly regarding his changing stances on immigration, and who goes versus who gets to stay, makes it very hard for Latinx undocumented immigrants to know what to believe. From my experience, undocumented Latinx immigrants, regardless of their education or literacy levels, have an equally hard time trusting the information about Trump’s proposed immigration policies that they receive through both Univision and other Spanish-language news sources.

Nonetheless, personal conversations which can take place with either welcoming U.S. citizens or other individuals residing in this county who have at least a basic understanding of how government functions and presidential limitations of power, can help instill a small, yet significant sense of security in the lives of undocumented immigrants who were already living in fear before Donald Trump showed up.

Whether residing in a new Latinx immigrant destination like Pittsburgh or a historic Latinx city like Los Angeles, the methods for creating safe and welcoming communities for undocumented immigrants are essentially the same: talk with your Latinx neighbors if you are capable of communicating with them (even if your Spanish—or any other language, feels a little rusty) and research ways to support. Become involved in “Welcoming” initiatives in your city/region that aim to keep all immigrants informed, safe, comfortable and active in their communities.

The fact that undocumented immigrants cannot vote also leaves them with an information gap when it comes to the election because there isn’t a focus on getting them accurate information on the candidates’ proposed policies.

Therefore, welcoming individuals and civic leaders and associations need to help fill in this information gap for undocumented immigrants in order to help ease their fear (even if just to a small extent), while simultaneously offering a genuine invitation for interaction and conversation.

***

Joanna Bernstein is a freelance writer living in Pittsburgh, PA covering issues on immigration and social/racial justice. She has been working as an advocate within the Latino immigrant community for the past five years. She holds a master’s degree in community and regional planning from the University of Oregon. You can follow her @JoannaPgh.