If you’re like me, you’re probably a bit electioned out.

In fact, after you reluctantly clicked on this, you must have thought it was going to be yet another woeful tale of childhood uncertainty, a lament of “Won’t someone please think of the children?”

But look, here’s the reality: Both before and after the election, my students were fine, and this story is about why:

I teach social studies in a large, diverse, high school with one of the highest percentages of foreign-born students in the New York City public school system.

The foreign-born students come from countries like (in no particular order) China, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Yemen, Egypt, Bangladesh, Mexico, Dominican Republic and Guatemala.

I have a lot of students who wouldn’t exactly hear Donald Trump’s campaign rhetoric as music to their ears.

In fact, on November 9, as I played with my phone before work, social media was blowing up with calls to surround the children with “safe spaces,” and extra levels of kindness. A non-profit I work with even cancelled their visit to my class so I can “just be with the kids.”

As a guy who teaches government to over 100 students who were born somewhere else, I knew I had a special kind of responsibility that day, but I’m not Robin Williams and I’m definitely not Oprah.

So I did what I always do.

I taught.

Starting in September I pounded away at the logistics of how exactly American presidential elections work. My students can tell you how the Electoral College works, what swing states are, what swing voters are and why Hillary and Donald only seemed to go to New York to briefly catch some sleep.

We studied successful and unsuccessful campaign ads, analyzed campaign slogans, discussed campaign finance and made pamphlets entitled “7 Habits of Highly Effective Presidential Candidates.”

The students delved deeply into Clinton and Trump and compared the two: from strengths, to bases, to weaknesses, to which the swing voters each one was banking on. Students thoroughly answered questions like “Who will win?,” “Who should win?” and “Which candidate is most aligned with your political, economic, and social values?”

So back to November 9:

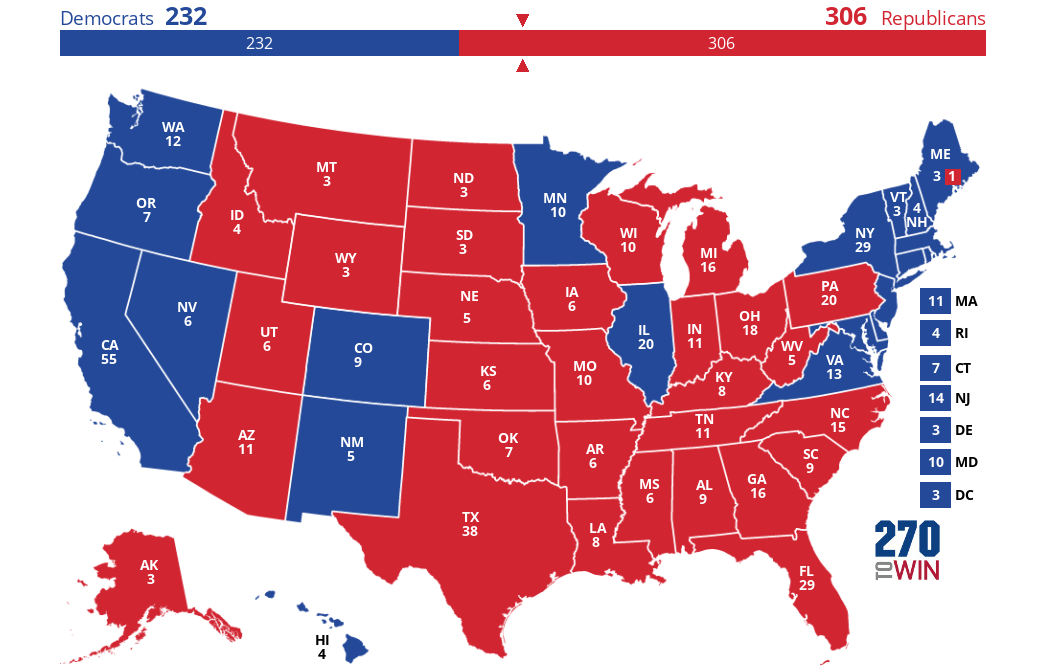

My first batch of students poured into class, and instead of seeing a bunch of sad faces, what I saw were smiling 16- and 17-year-olds ribbing me. We had taken screenshots of Electoral Maps each of us made on 270towin.com, and out of the 35 people in the class, mine was the most wrong.

(This is not mine. It’s kind of what the map looks like now.)

And then questions came, which were also in turn largely answered by the students themselves.

“Should the students who are undocumented worry about getting deported now?”

No, but if they commit a crime the process of deporting them may be easier.

“Will the Muslim kids get deported?”

No, but it may be harder for future Muslim kids to come here, just like the anti-Catholic immigration laws of the 1920s.

At the end of the class, the kids left with the same jolly faces they came in with—many of them even remembering a passing reference to my birthday I made months easier. First bumps and kind words were exchanged.

The overall takeaway is this: My students didn’t need a special safe place because their knowledge created the safe space.

Nobody was traumatically shocked because they knew how the process works.

“The charismatic businessmen with the catchy slogan beat the experienced politician with the familiar last name. This is how he did it.”

In order for a democracy to work, there has to be buy-in from the losing side. Not to be paternalistic, but many of my students, especially the Uzbeks, Dominicans and Russians, come from countries with iffy track records of democracy. They found our process kind of interesting.

Having the candidate you like lose, being aware of what that means and knowing what to do next is why my new Americans did not succumb to post-election hysteria.

***

Eric Cortes is a teacher and a writer. He tweets from @PoliteEric.