There was much praise thrust onto the African-American and Latinx electorates during the campaign of Hillary Clinton, casting such demographics as the newfound “emerging Democratic majority.” For Democrats, the approach did not extend far beyond pandering to the fear of a potential, and now realized, President Donald Trump. In the aftermath, the Democratic Party has attempted to blame multiple outlets (and countries) for the unexpected loss, yet few recognize the underwhelming performance among communities of color.

The numbers show it was the Democrats’ approach that failed, relying on the supposed unpopular opinion of the Republican candidate, now president-elect, Donald Trump. In a post-election analysis, Molly Ball of The Atlantic wrote that “eight percent of African American voters under 30 chose a third-party candidate, as did 5 percent of Latinos under 30, according to an analysis of the election results by the Democratic pollster Cornell Belcher.” Ball adds that these “protest votes” that Belcher described “were enough to seal Clinton’s fate, even though this year’s electorate was just as diverse as 2012’s, and Trump did not do any better than Romney among young, minority voters.”

The critical nature of the Latinx electorate was examined more in-depth before the election by Priscilla Alvarez when she wrote the following for The Atlantic: “…the Latino population in the United States is young, which means they’re likely to make up a larger share of eligible voters in the future. According to the Pew Research Center, millennials make up roughly a quarter of Latinos in the United States, while Latinos younger than 18 make up 32 percent.” Alvarez further explains that such a contingent comprises half of the Latinx electorate, a blossoming behemoth.

For the Democratic Party, the youth, or “millennial” vote was deemed critical to success.

The approach failed.

It failed to fully capture millennials in African-American and Latinx communities, as the approach seldom ventured past attacks of Trump’s inabilities to lead, rather than the substance of policies proposed by Mrs. Clinton.

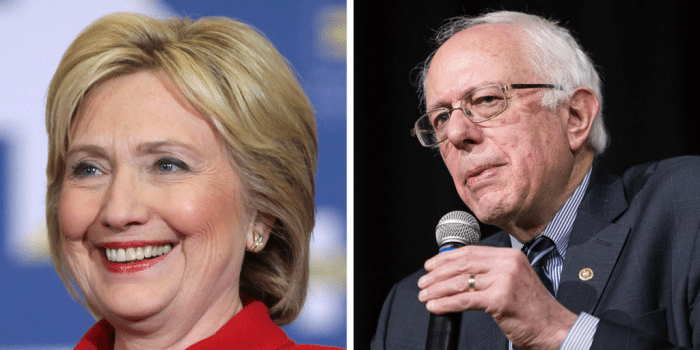

Lackluster support for Clinton was exposed at various points during the primary season, for example, as The Los Angeles Times reported in June, before the California primary (a contest Clinton won):

The final Los Angeles Times/USC survey… shows Clinton and [Bernie] Sanders tied at 44% among eligible Democratic primary Latino voters… When respondents under age 50 are separated out, those younger Latinos choose Sanders over Clinton by 58% to 31%. Older Latino respondents, above age 50, still heavily support Clinton, 69% to 16%.

The critical issue that arose in the national election became encouraging these segments of the population to vote. For African-Americans and Latinxs, this presented an uncomfortable yet real problem for the Clinton campaign. The candidate was flawed, and an unfavorable opinion for Clinton was expressed in polling. For African-Americans “43 percent of Obama supporters under age 40 were ‘very enthusiastic’ about him in 2012, just 24 percent of Clinton supporters feel the same way about her now,” according to a Washington Post report from October.

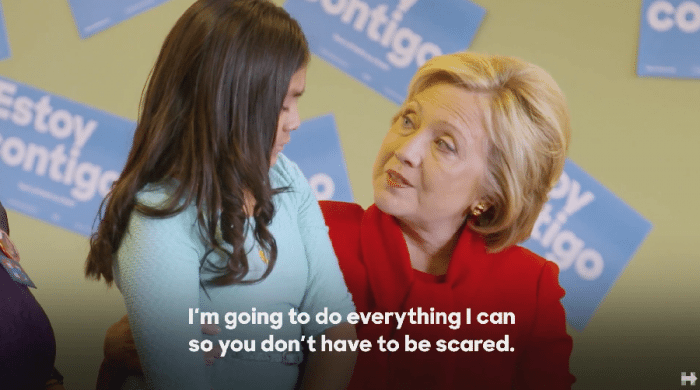

In another WashPo report, Latinx millennials showcased a similar disdain for Clinton where “two-thirds… say their support is more a vote against Trump than a vote for her.” Such sentiment was also expressed in a Guardian story where Latinxs’ support for Clinton was in part a preemptive strike against the divisive rhetoric of Trump.

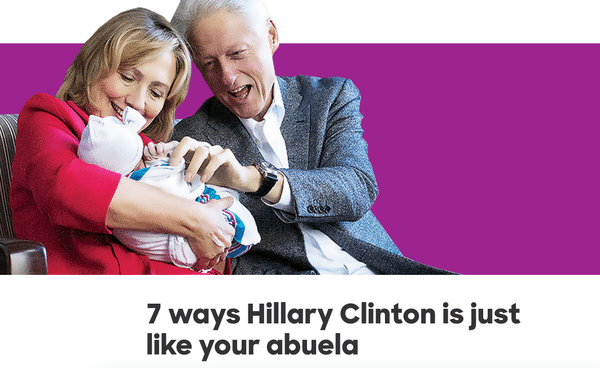

The underwhelming performance stems from resentment harbored towards policies instituted in the past, and perhaps, policies shrouded in stereotypical appeal. Doubts arose, as explained in The New York Times, about Clinton and her sincerity in combatting racism due to “legislation that President Bill Clinton signed imposing stiff sentences on non-violent offenders,” and in a piece from The Huffington Post that detailed her role in the coup d’état in Honduras and the burgeoning Central American refugee crisis.

For activists of the Black Lives Matter movement, disdain for Clinton pertained to issues relating to police-brutality and mass incarceration. It was a part of a more confrontational approach, in which political leaders must be held accountable, and more is expected of politicians to condemn the recent wave of extrajudicial police-killings.

The 2016 general election became the medium through which African-American activists held Clinton, and even Sanders accountable, as they “placed criminal-justice reform on the political agenda. Both Sanders and Clinton have been falling over each other talking about the need for reform and the persistence of institutionalized racism.”

For Clinton, association with former President Bill Clinton handicapped the campaign. A Times’ examination of the African-American population in Milwaukee showed how this condemnation of Clinton contributed to the electoral loss. Such sentiment was expressed in poetic terms, “Milwaukee is tired. Both of them are terrible. They never do anything for us anyways.”

For the Latinx community, the same indifference towards Clinton always existed. Where immigration appeared to be the core issue at stake, Clinton faltered. As the HuffPo reported, for example, Clinton had not curried favor among immigrant rights activists: “I can’t see Clinton doing anything different on immigration… the only way to move forward is to organize ourselves.”

There was also unjust burden thrust onto the Latinx electorate during the 2016 general election, as written in American Prospect. Two sentences in particular stand out: “the challenge for Latinos is to translate their community’s latent voting power into actual ballots cast,” and the paternalistic tone of “the story of the Latino electorate, Pew [Research Center] data show, is one of vast unrealized potential.”

The post-election data from the Pew showed that Clinton underperformed Obama among Latinxs. Clinton’s loss, therefore, falls on the shoulders of our communities. The lack of a coherent message and lack of investment in the Latinx electorate was manifested in a poor electoral showing for Democrats.

In hindsight, this was an inherent failure, Clinton did not deserve the African-American vote, nor did she deserve the Latinx vote. As is often the case with political upheaval on such a grand scale, the flaws of the candidate, and the establishment that anointed her, are not the focus. Clinton and her performance in the 2016 general election was underwhelming.

For the Latinx and African-American electorates, it became a matter of swallowing pride when a vote was cast for Clinton. It became an expectation. The exploited were expected to vote for a candidate, and an establishment that caters to the needs of the people on a quadrennial basis. In that strategic blunder, the 2016 election was lost. It was not a matter of an opponent out-performing expectations. It was a lack of intuitive insight, a failure to recognize that years of mismanagement were not to be undone by eight years of supposed change.

The Democratic Party relied on a candidate that possessed an enormous amount of flaws, hoping the public might forgive the choice as a “pleasant alternative.” The choice backfired, and now, in the aftermath, there appears in the ashes a possible blueprint for future successes. Adopt into the conversation the diverse groups that compromise a significant part of the Democratic electorate—do not solely peddle fear or showcase policies designed to combat the rise of a xenophobic demagogue.

The inclusion of people of color into the conversation, the process (and the establishment) illuminates a successful path to the future. Rhetoric does not earn votes, it hampers campaigns. Actions, however, speak far louder than the recycled words of a candidate.

***

Nathaniel Santos Hernández is a graduate of the University of Maine, Orono, with a degree in Anthropology. You can follow him on Twitter @saint_nate12.