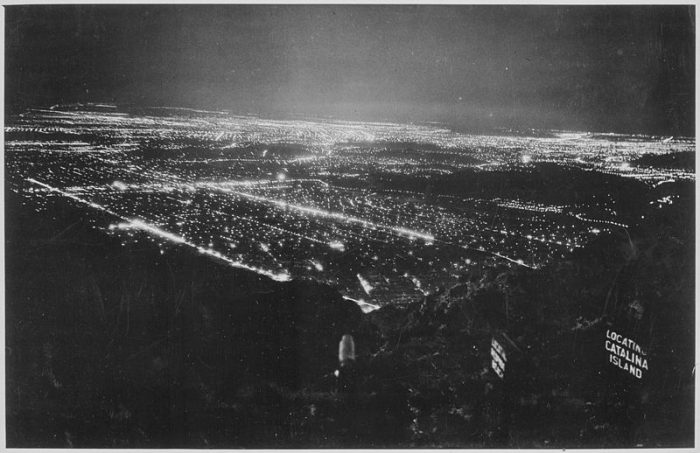

Late 19th century photo from the state of Chihuahua in Mexico (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

In Donald Trump’s America, my great-grandfather, Jesús Chavira, would be treated as a societal menace.

But Jesús Chavira, a Mexican teenager, was fortunate to have crossed the border nearly 150 years ago. He faced no immigration or work barriers, and his many descendants became productive citizens of the United States.

Orphaned in Ciudad Camargo, Chihuahua, Jesús found a new home with his grandfather Gregorio, who lived alone at his ranch. Jesús provided company and much-needed help on the ranch just outside Satevó, a 300-year-old village surrounded by fertile plains and livestock herds. It was a bittersweet time. Gregorio was comforted to have Jesús by his side. But he knew his chronic ailments meant that he was approaching death. Gregorio also knew that Jesús would not be able to keep the ranch when he died.

It was certain that land-hungry usurpers would surely kill Jesús to steal the ranch. So Gregorio told his grandson that as soon as he died, Jesús should ride to Texas, where he had a good chance of finding work and surviving.

Gregorio died one day in 1870 and Jesús, just 14 years old and astride a white mare, headed to Fort Davis, a U.S. Cavalry base in far West Texas.

A portion of Fort Davis National Historic Site in the Texas town of Fort Davis, Texas. (Carol M. Highsmith for The Library of Congress)

A few days later, the rangy youth made it to the military fort, where he was hired as a stable boy.

The army was at war with the Apaches and Comanche, and Jesús would later recount how he sometimes accompanied the soldiers on their mounted patrols. He showed tracking skills, and so he was given the added duties of scouting for indigenous people on the move.

Over time, my great-grandfather settled in the inhospitable West Texas desert and married Estefana Molina, herself orphaned at an early age.

By 1906, they had eight children. The eldest was my grandfather, José.

In long chats with me, my grandfather José recalled how the family struggled to make a living growing crops and raising livestock in a hard land made all the harder by virulent racism. The anti-Mexican sentiment was so intense, said my grandfather, that European-American drifters would shoot at them from a distance.

“My father decided to move away to a safer place,” José recounted. “He couldn’t fight back, because we were just kids and he didn’t even own a gun. Even if he did defend himself, the [Texas] Rangers would have killed him. The gringos made our lives very difficult.”

The Chavira story is representative of what Mexicans had to endure in turn-of-the century Texas. If Jesús did not have to bother with the Border Patrol —not created until 1924—h e and his family were often greeted with racist hostility.

But the history of the Chaviras highlights something else.

They, like many others who came to the North, worked hard for little money. Future Chaviras would serve the United States in three wars and hope for a certain degree of respect and fair play.

In 1919, José, illiterate because there were no schools where he grew up, would marry my grandmother María Ramírez in Sierra Blanca, Texas. For several years, they worked as migrant cotton-pickers, ranging through Texas and into Oklahoma.

The work was very hard and living conditions inhumane. More than once they were cheated out of pay.

José and María were pained by the fact that their children, David and Elena, rarely attended school with the family on the road for months on end. My father, David, had vague memories of school as a six-year-old in Sierra Blanca.

“It was a joke,” he said. “The teacher just had us sing songs, or left us alone to spend time with her boyfriend.”

To ensure their children’s education, José and María moved to El Paso, where their children could attend school full-time.

“I was eight when I started the first grade,” my father told me. “I couldn’t read any letters and didn’t speak English.”

My grandfather had to find work in a border town with high unemployment. It was in 1928 and the times became increasingly difficult with the onset of the Great Depression.

José turned to a street corner where day laborers were hired for day labor.

“I remember my first day on that corner,” said José. “A gringo in a truck drove up, looked us over and picked a few men, me included. We were put to work at a construction site and I did what I could to show him that I was strong, because if you seemed weak or slow, the gringo said you that you do not come back; he told me that I could return.”

As a teenage my father hopped freight trains to California, where he picked crops.

He also took a long break from high school to work for the Civilian Conservation Corps, one of President Franklin Roosevelt’s work programs.

“My dad was pretty sad when I did that,” my father recalled. “He was sure I would never graduate from high school.”

But at the age of 21, David graduated from El Paso’s Bowie High School and entered directly into the United States Army. His tour began a few months before the attack on Pearl Harbor and continued until the end of World War II.

“When I left the Army, I really thought that as someone who graduated high school, which was rare in those years, and with the time I spent in the army I would get a good job,” my father told me. “I discovered that El Paso had not changed and that, above all, I was Mexican. And for Mexicans, decent jobs hardly existed.”

My father and my mother Helena headed to Los Angeles, where my two brothers and I were born.

José and María also migrated to L.A. and continued to work at the grueling and poorly paid jobs set aside for Mexicans. Though José (a native of Shafter, Texas) was a U.S. citizen, he was unable to achieve anything above manual labor. María, a legal resident, for years worked cleaning buses, streetcars and, in her last years, hospital rooms.

My brothers and I graduated from college and pursued professional careers.

Today, some 147 years after a brave teenage orphan was directed towards Texas, his descendants include a multi-millionaire real estate investor, two journalists, a police officer, a scientist, marketing and public relations directors, military vets and a university lecturer.

The current wave of xenophobia, highlighted by anti-immigrant policies aren’t new to the U.S. Growing up in 1950’s and 60’s Los Angeles, my family and I heard such sentiments openly expressed. European-Americans at one time or another called us greasers or beaners, or yelled at us, “Go back to Mexico!”

We Mexicans have endured all manner of racism and marginalization. We have lived through mass deportations during the Great Depression and Operation Wetback in 1952.

What I say to those who mischaracterize us as aliens is that we have always been in the Southwest. Who else but Mexicans under Spanish colonial rule founded and named San Antonio, El Paso, Albuquerque, San Diego, Los Angeles, Sacramento and San Francisco? Our ancestors were on hand to greet the first European-Americans to arrive in those settlements.

Trump and the Trumpistas can do everything in their power to sweep us out of the U.S. In the end, they will fail.

Aquí estamos y no nos vamos.

We are here and we are not leaving.

***