Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this piece was published here.

SALINAS, CA — Fremont Peak looms over the fields where migrant farmworkers harvest the land up and down the Salinas Valley. As one of the summits of the Gabilan Range, the peak is visible throughout Salinas, the major city in the agricultural hub.

The best view of Fremont Peak is from the East Salinas elementary school, Monte Bella, meaning “Beautiful Mountain” in Italian. Across the street from lettuce and strawberry rows, the school gives you scenery of the mountain range sloping dramatically up from the Valley’s crops. At the top of these evergreen slopes, stands the peak.

But the school was not always called Monte Bella. In January 2016, the Alisal Union School District changed its name to Monte Bella, after the local neighborhood, which is almost entirely Latinx —in an agricultural city of 156,000 that is 75 percent Latinx— nearly 95 percent of whom have Mexican ancestry.

Monte Bella’s original name, Tiburcio Vásquez Elementary School, gained widespread attention when the institution was built in 2012. Named unanimously by the school board, community members and a few ethical and unethical elected officials, the school commemorated a 19th century bandit whose Californio (Mexican inhabitants of the state) roots traced back to the settlement of California.

Following the school board’s initial announcement, many authorities and residents (though many not from the neighborhood) criticized the school’s name. The Monterey County Deputy Sheriff’s Association expressed “extreme disappointment” because the school honored a man comparable to contemporaneous murder and gangs.

Though they had no apparent authority in early childhood education, the Association claimed that, because Vásquez was a bandit and “Salinas sees more than its fair share of gang violence,” the predominantly Latinx elementary school students will proliferate gangs from the name of an elementary school.

(Under that logic, I suppose all students of the Washington Union School District are inclined to implicitly support a slave society since George Washington was a slave owner, who did free his slaves after he died, only to tacitly approve of the ownership of people. But I digress.)

The school board then renamed it, and it has since remained the “Beautiful Mountain” school. Although it is a spectacular view up to the summit, the juxtaposition between Fremont Peak and the Monte Bella School provides insight into the history and people of this area.

John Charles Fremont

The peak takes its name after John Charles Fremont, an American captain who occupied the summit in March 1846 when California was Alta California, Mexico. Outnumbered, he fortified the position and raised an American flag.

Upon receiving word from Mexican authorities, the U.S. Consul in Monterey, Thomas O. Larkin, ordered Fremont to leave the peak: he had illegally attempted to invade a sovereign nation before the Mexican-American War started in April. The flagpole also fell down after a windstorm, apparently further dissuading the captain to stay.

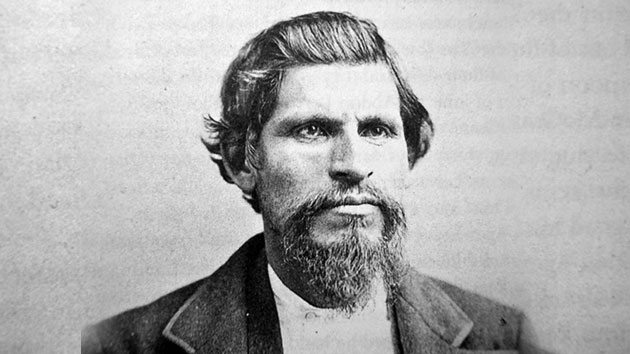

John C. Fremont in 1856. (Source: Smithsonian Institute)

Fremont would go on to lead the California battalion for part of the actual war. But, according to the California State Parks’ history of Fremont, General Stephen Kearny had him arrested, court-martialed and “found guilty of mutiny, disobedience and ‘conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline’” in 1847.

While his mutiny conviction would later be dropped by presidential pardon, Fremont’s notoriety does not stop there: prior to his failed flag raise, he annihilated an entire Klammath village in Oregon. He also murdered an unarmed Californio father and his two sons at San Pedro Point near Mission San Rafael, later profiting immensely from land he illegally stole (or “squatted” depending on your euphemism) from Mexican and Native American landowners in California.

After the Mexican-American War, Fremont had stints as the first U.S. Senator for California (for less than 2 years), a failed presidential contender in 1856 and an ineffective Civil War general. To his credit, he ordered the freedom of slaves under his jurisdiction in 1861, approximately two years before Lincoln delivered the Emancipation Proclamation. He even considered unseating fellow Republican, President Abraham Lincoln, during the 1864 cycle.

He would later lose tremendously in the railroad industry and be appointed as governor of Arizona. Born on January 21, 1813 in Savannah, Georgia, Fremont died in New York on July 13, 1890.

Tiburcio Vásquez

Vásquez’s life can be seen from Fremont Peak: born in Monterey, Alta California, Mexico to the West on August 11, 1835, lynched in San Jose, California, United States to the North on March 19, 1875.

Son to an educated, affluent Californio family that settled here during the 1775 Anza expedition, Vásquez lost much of his status in society when Americans invaded Mexican lands in 1846. He was a controversial figure in California history, committing crime in the name of the Californio people. Most observers have polarized views of him as either a Robin Hood or outlaw. Regardless of one’s take, the context in which Vásquez lived must be understood.

He began living outside American law when one of his friends or (Vásquez himself) killed William Hardmount, the American constable (akin to lawman), at a Monterey fandango on September 2, 1854. There has been no consensus on who killed Hardmount.

As John Boessenecker writes in the biography Bandido: The Life and Times of Tiburcio Vásquez, “the crowd was a mixture of Californios, Mexicans, and Anglos, all vying for the attentions of the dancing señoritas.” Vasquez and a few friends “were half-drunk” when a brawl broke out at the party, whereby a fight started and Anastacio García, a friend of Vásquez’s struck a guest with a water pitcher. Someone sent Hardmount to settle the dispute.

Like many other issues in history, fights over women and alcohol often signify other, systemic issues. For Californios and Mexicans at the time, this started with the loss of 12 million acres of land through racially motivated illegal incursions of Manifest Destiny during the Mexican-American War. Existing populations would be criminalized based on race to sustain power for white populations, resulting in discriminatory laws like the 1855 Greaser Law and Foreign Miners Tax targeting Native Americans, Californios, Mexicans, Asians, immigrants and nonwhite peoples. Further, extremely high incarceration rates in San Quentin Prison as well as lynchings of Mexicans at rates comparable to Black people in the American South all encompassed many of the experiences during Vasquez’s life.

Accounts conflict, but Hardmount made his way to García, whereby guns drew and someone killed the American lawman. The Monterey County Superior Court ultimately concluded García indeed killed Hardmount, though some like Deputy Sheriff Truman Beeman and Vásquez’s friend, Abdon Levia, alleged Vásquez did it.

Vásquez and García fled the area while their other friend José Higuera was captured and lynched by a mob the next day. In the November 1965 edition of Real West magazine, Dick Cox described that García was eventually captured by authorities but a mob later broke into the jail and hung him. White mob justice —particularly against Mexicans and Californios— was not uncommon at the time.

The altercation and aftermath greatly influenced Vásquez’s career outside of American law. Cox wrote that Vásquez took to horse and cattle stealing that would land him in and out of San Quentin State Prison, where he “probably obtained his ‘college education’ in crime during that stay.”

Beyond this, Vásquez represented the tragedy of the Californio people. He even justified his unlawful actions through this perspective. Boessenecker’s biography details an account between Vasquez and a San Francisco Bulletin reporter regarding the outlaw’s decision to choose his path: “If you behaved yourself they wouldn’t meddle with you, would they?” to which Vásquez replied “Oh, yes, they would. That didn’t make any difference.”

But Vásquez also killed white Americans. He stole cattle, money and other valuable goods throughout California. And most famously, the Californio bandit evaded law enforcement for years, breaking American law and its social hierarchy.

Just as Fremont, Vásquez’s context is paramount to understand his relevance today. The Monte Bella School serves predominantly Mexican American schoolchildren in a neighborhood that is almost entirely Latinx, situated in a city that is three-quarters Latinx.

Entrance to Monte Bella Elementary School with Fremont Peak in the distance.

Dr. Ramón Chacón, the late professor emeritus of ethnic studies and history Santa Clara University who passed away in February, wrote a piece historicizing and justifying the Tiburcio Vásquez School’s name as part of Mexican American identity.

As a form of community building, Chacón contended, “racial minorities are claiming citizenship and want to see themselves in a cultural context.” To supporters, naming it the Tiburcio Vásquez School affirmed the history of Mexican Americans in the area.

Despite potential cultural benefits, it seems like returning to the school’s first name is implausible. A controversial figure could impede on the work of teachers, administrators and pupils. That is not to say, as the Sheriff’s Association racially charged, that the school’s very name could incite first graders towards gang violence. And above all, Alisal residents ultimately said that Tiburcio Vásquez might serve as a good name for a community center in the area, but not a school.

But by arguing that Vásquez is too controversial, the same recognition should go to a figure like Fremont, who has cities, schools, parks and streets named after him. This state (and nation) memorialize an institutional murderer that conducted ethnic cleansing and was eventually court-martialed during an unjust war. Seems like the tar-stained pot is calling the kettle black.

The next time you visit Salinas, look across picturesque fields up to the “Beautiful Mountain” where Fremont vainly stood (barring a windstorm). The juxtaposition between the peak and Monte Bella Elementary School, formerly Tiburcio Vásquez, is almost comical. Our view is definitively more through Fremont’s than Vásquez’s, despite the culpability of both and the atrocities of the former.

I suggest you put these histories into perspective.

***

Eduardo Cuevas is an indebted college graduate who writes about history and politics. He hails from his Chicanx community of Salinas, California, although he went to Santa Clara University and studied history and English on indigenous burial grounds. In his spare time, he likes to ride his bike and eat his mother’s nopales.