By Omaya Sosa Pascual y Jeniffer Wiscovitch Padilla

Dr. Susoni Metropolitan Hospital in Arecibo (Omaya Sosa Pascual | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo)

More than two weeks after a catastrophe that devastated Puerto Rico, the crisis in the island’s hospitals as a result of Hurricane María’s landfall and the direct impact on patient health is a daily issue.

The lack of information, misinformation and contradicting data regarding the real status of these institutions from the government has been constant.

Last Tuesday, for example, Gov. Ricardo Rosselló touted as an achievement that 63 of the island’s 69 hospitals were “operational.” He never explained in detail how the government went from having 56 hospitals closed the prior week, as Health Secretary Rafael Rodríguez-Mercado said at that time, to having reopened practically all of them.

The great question is: What does “operational” mean?

That same day, the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI in Spanish) visited the Pavía and Susoni hospitals in Arecibo and the Buen Samaritano in Aguadilla and confirmed that none of them were ready to admit critical patients, despite being on the list of hospitals released by the government. Pavía Arecibo, El Buen Samaritano and Ryder in Humacao, which was closed last Friday, are particularly important because they are three of the seven hospitals the governor designated as medical centers to serve as regional anchors. These hospitals channel emergencies from all of the other institutions, and they should presumably be functioning better than the rest and with priority support from the local and federal governments. The other four anchor regional hospitals are Doctor´s Center in Manatí, HIMA Fajardo, HIMA Caguas and La Concepción in San Germán.

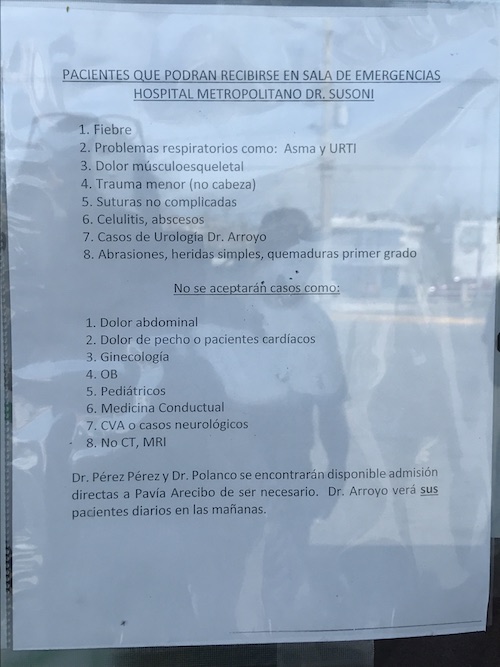

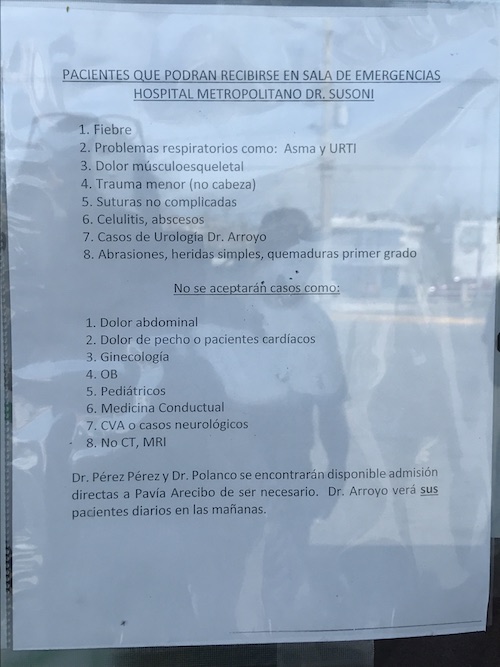

Susoni, an institution which lost its roofing in several areas, as the CPI confirmed, was practically closed, attending only fevers, minor lacerations, and other minor illnesses, according to a sign taped to the door.

On Friday, Rosselló insisted at his morning press conference that there were 68 hospitals already operating. On the government’s list posted online Friday, there were 66, which on Sunday still included the Ryder Hospital in Humacao, a institution the U.S. Army evacuated Thursday because its power generator has been damaged. That same day, the hospital was closed, according to an updated list sent that night by Rosy Santiago, director of La Fortaleza’s Central Communications Office.

It is still unknown how many people have died at the 69 hospitals and other healthcare institutions since Hurricane María struck on September 20, where morgues were at full capacity during the first week after the storm, according to a CPI investigation.

But a sample is often enough proof. At the Pavía in Arecibo alone, which has the capacity for 192 patients, 49 died during the first 10 days after María, the institution’s administrator, José Luis Rodríguez, told the CPI. He said none of those deaths were associated “directly” with the hurricane, and acknowledged that the hospital was not in a position to admit critical patients until the government brought a power generator that could support the air conditioning system. Despite this, he confessed to the CPI that at that time he had a census of 98 patients and that they were performing emergency surgeries with portable air conditioners in two operating rooms.

The next day, on Wednesday, the Army brought him a power generator, he said.

However, this hospital that “operated” for almost two weeks without air conditioning or electricity or a generator, was designated by the government as one of the priority and anchor hospitals to receive critical cases in the region.

The Buen Samaritano in Aguadilla operated that same way, but in the end was not so lucky.

The morgue in the Good Samaritan Hospital in Aguadilla (Jeniffer Wiscovitch Padilla | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo)

The rush to deal with the avalanche of patients that came after the hurricane was mainly due to accidents, head trauma, neck, eyes and even situations caused by crime, in addition to natural and cesarean deliveries, said the hospital’s Medical Director, Dr. Arturo Cedeño.

In addition, elderly centers began sending their residents to the hospital for a lack of diesel to operate their power plants.

Cedeño acknowledged that the institution had deaths related to the hurricane’s landfall, including dialysis patients who were unable to complete their treatment and who arrived with too much fluid and pneumonia. Its morgue, which has room for 14 corpses, was filled to capacity because it also had to house bodies of people who were not hospital patients, since it is the area’s only morgue with refrigeration capacity.

Two weeks after María, only the emergency room was “operating,” but without air conditioning, and fungus and a bad smell had taken over the place, as the CPI confirmed during a tour of the institution. Temperatures there had reached 90 degrees. For that reason, the hospital had to resort to the use of wet sheets and ice packs so that patients’ body temperatures did not increase. The operating room, like in other areas of the hospital, had been shut down because they did not have the appropriate temperature for use, and because of the proliferation of moisture and fungus due to the high temperatures.

The government’s promises to constantly supply water and diesel, and a power generator from FEMA that could sustain the operation of the only institution with secondary and tertiary services in the region, never materialized, Dr. Cedeño said in an interview.

Faced with the obvious disaster in the hospitals visited, the CPI tried to get the government to define what it means to declare a hospital “operational,” and explain why the status of each hospital is not clearly communicated to the public, so that they can avoid risking their lives by going with emergencies to places like those described above. A week later, La Fortaleza’s Public Affairs Secretary Ramón Rosario, offered his answer in an interview on Friday. He explained that those are institutions that the government and the U.S. Health and Human Services Department (HHS) have evaluated, and both agencies have determined that their structures are “physically operational” and have accepted patients. This puts them on the list of hospitals receiving priority assistance from the Puerto Rican government, HHS, the Corps of Engineers, and the U.S. Army.

The classification has nothing to do with the services they are offering and under which conditions they are doing it, and includes a wide range of circumstances, from a hospital that is performing complex surgeries, to the one that can not attend to births such as Susoni, Rosario admitted.

“There will be no way to get into a hospital and find it to be perfect. We are working with what we inherited from the hurricane. They are not beautiful, that’s the truth,” Rosario said.

“When we say operational, it’s that they are receiving patients,” he insisted.

The CPI asked why the government was not clearer in informing the citizens, as they were risking the lives of people every day with the lack of information, and Rosario disagreed because the health system was allegedly functioning “as usual.”

When a patient arrives at a hospital emergency room that cannot provide the service they need, they are transferred to another hospital. This is despite the fact that in an emergency, the time that passes before receiving proper medical assistance is often a matter of life and death.

With the exception of the Puerto Rico Medical Center, Rosario said, the other hospitals on the island are private, so it is up to each institution to provide the public with information about what services it is offering and what limitations it has—not the government. However, by law, the Department of Health is responsible for supervising, overseeing and granting or withdrawing operating licenses to all hospitals in Puerto Rico.

Ten days ago, the CPI sent an interview request to Health Secretary Dr. Rafael Rodríguez-Mercado, who is really the expert on the subject of hospitals and the person responsible through a constitutional mandate to ensure health in Puerto Rico, but it has been impossible to get a statement from him.

After he spoke to the CPI about the hospital situation and candidly said there were additional deaths to those revealed as related to Hurricane María two weeks ago, his public relations adviser, Peter Quiñones, has said all questions on the subject will be answered by Rosario, who is a lawyer by profession. The CPI learned that Rosario himself allegedly stopped Rodríguez-Mercado from making make public comments. Rosario denied that this was the case and attributed Rodríguez-Mercado’s sudden lack of availability to being “very busy” attending to emergency-related situations.