Enrique Peña Nieto meets with Donald Trump, G-20 Hamburg summit, July 2017 (Photo by the Mexican Government)

Long before Donald Trump dubbed it “the worst trade deal ever signed,” the North American Free Trade Agreement had been portrayed as a threat to U.S. workers.

In 1992, for example, independent presidential candidate Ross Perot accused Mexico of paying “a dollar an hour for labor” and warned that NAFTA would create a “giant sucking sound” as investment went south of the border. And that’s before NAFTA even came into effect, on January 1, 1994.

Fears that Mexico’s allegedly substandard labor conditions have hurt American workers reached new heights under Trump, who has threatened to withdraw the U.S. from NAFTA if Mexico doesn’t stop “taking advantage.”

I will renegotiate NAFTA. If I can’t make a great deal, we’re going to tear it up. We’re going to get this economy running again. #Debate

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 20, 2016

As a Mexican citizen, I find such rhetoric offensive. But as a human rights professor and lawyer, I also feel compelled to examine Mexico’s record on labor rights. If Trump is right that Mexico doesn’t respect workers’ rights, then NAFTA’s current renegotiation could be an opportunity to improve labor standards in my country—and help keep NAFTA alive in the process.

A Failed Experiment

From a strictly legal perspective, American notions about Mexico’s bad working conditions are unsubstantiated. Article 123 of the Mexican Constitution grants workers the right to organize and strike, provides protections for women and children, mandates an eight-hour workday and establishes a national minimum wage.

President Bill Clinton signed the North American Free Trade Agreement into law in 1993. (Public Domain)

Mexicans take pride in their 1917 constitution, which was the first in the world to include social rights.

Nonetheless, when NAFTA was in development, both the U.S. and Canada feared that free trade would lead working conditions in their countries to decline. So in 1993, the three North American governments signed a NAFTA side agreement, the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation.

The document dictates that certain labor rights —including freedom of association, collective bargaining and equal pay for men and women— must be respected in all NAFTA countries. It also prohibits forced labor and guarantees protections for migrant workers.

In theory, these principles are enforced cooperatively in each NAFTA signatory nation through intergovernmental consultations, independent evaluations and dispute settlement.

Workers Left Unprotected

After two decades, however, the experiment on cross-border labor cooperation seems to me to have failed. It’s mostly Mexican workers, though —not their American or Canadian counterparts— who have suffered from substandard working conditions south of the border.

American manufacturing jobs have indeed decreased since 1994 —some 5.6 million of them disappeared between 2000 and 2010 alone— but estimates suggest that 87 percent were lost to automation rather than trade.

Meanwhile, Mexico’s minimum wage —currently 88.36 pesos a day, around $4.60— is not enough money to buy what economists call the “basic basket of goods” for a single worker —beans, tortillas, eggs, some meat— much less to support a family.

In 1994, the minimum wage of 15.27 pesos a day amounted to $4.92. So, thanks to inflation, low-skill Mexican workers actually have less purchasing power than they did before NAFTA.

For decades, separate and apart from NAFTA, the Mexican government has also been violating the constitutional rights of workers. Under the Revolutionary Institutional Party, which ruled Mexico uncontested for nearly the entire 20th century, federal officials exerted extensive power over labor unions.

Through an alliance with the Confederation of Mexican Workers, a powerful group of unions, the PRI empowered labor bosses who supported its agenda, whether they represented union members well or not. To marginalize more independent unions, it created a series of legal hoops that few manage to actually jump through.

This system hobbled collective bargaining throughout the 20th century, preventing labor rights from progressing apace with Mexico’s economic growth. When the opposition National Action Party finally wrested the presidency from the PRI in 2000, it did not tackle this problem.

In fact, in 2012, Mexican labor law was actually reformed to give employers more flexibility in determining working conditions.

Canada’s Solution

Paradoxically, then, I believe NAFTA may have actually worsened working conditions in Mexico over the past quarter century. It incentivized businesses to invest in the country accompanied by a side agreement that did nothing to establish unified worker protections across the North America region.

Over the past 23 years, workers in the U.S., Canada and Mexico have filed nearly 40 complaints before national labor authorities, decrying union busting, shoddy health conditions and lax safety regulations. None has resulted in concrete action like legislative reform.

Today, the failure to effectively address differing labor conditions in NAFTA countries has put the entire deal’s future at risk.

Unlike Trump, who wants to simply repeal NAFTA, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has proposed modernizing it by implementing strong and progressive labor standards across North America.

Canadian officials reason that if Mexican unions gain more power, they could push wages up for the benefit of the entire North American region. In October, Trudeau called on the Mexican Senate to bring freedom of association and collective bargaining in Mexico into compliance with international labor standards.

Senators applauded Trudeau’s proposal, but business leaders not so much. Bosco de la Vega, president of the National Farming Council, retorted that improving NAFTA means more trade, not “intervening in labor markets.”

A Regional Problem

To my mind, the Canadian proposal is a sensible update for an old deal. In the long run, Mexico’s economic growth will hinge on sustainable business practices.

However, I disagree that Mexico’s precarious working conditions are Mexico’s problem to solve. The U.S., too, has seen the rewards of looking the other way on Mexican human rights.

During Jimmy Carter’s administration, the U.S. was looking to invest in Mexico—its “most promising new source of oil,” according to an internal memo leaked to The Washington Post in December 1978.

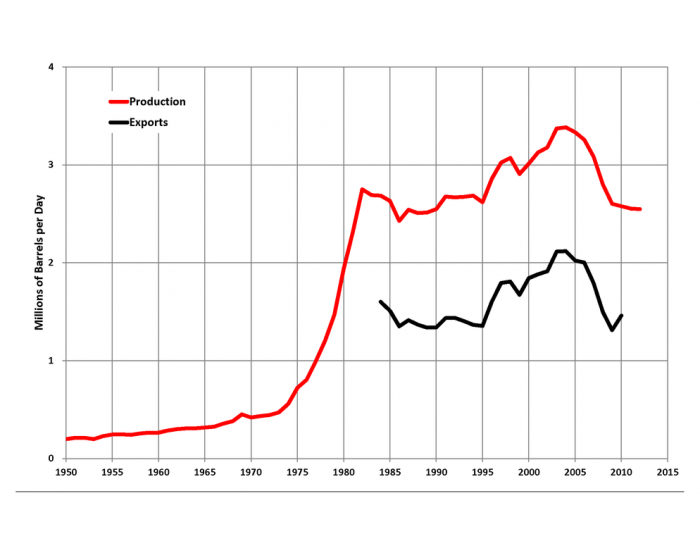

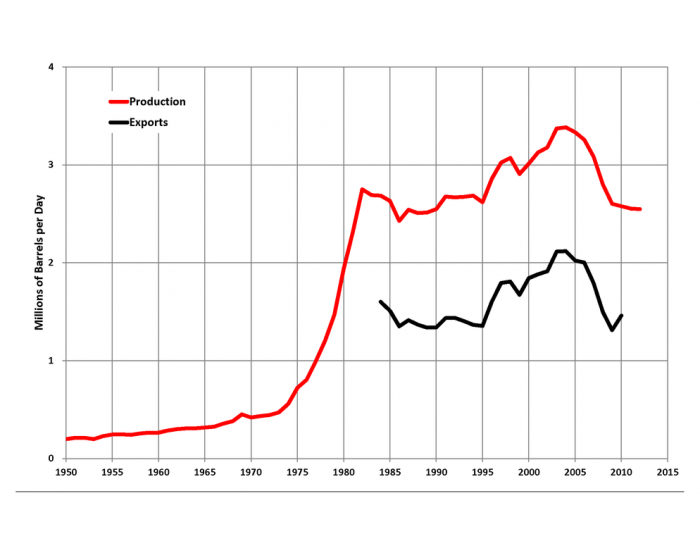

Oil production in Mexico, 1950-2012 (Graphic by Plazak/Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

The memo acknowledged that Mexico’s human rights record left room for “significant improvement,” citing the PRI government’s tendency to persecute its opposition.

To secure privileged access to Mexican oil resources, though, Carter officials determined that “it would be ill-advised and counter-productive” for the U.S. “to take Mexico to task publicly for its violations of human rights.” That assessment included unenforced workers’ rights.

A similar logic seems to have underpinned NAFTA. All three economies have generally benefited from the uptick in trade between Canada, Mexico and the U.S., which target=”_blank”increased from $290 billion in 1993 to over $1.1 trillion in 2016.

Even the American industries hit hardest by job loss are among NAFTA’s major beneficiaries. For carmakers and textile manufacturers, access to cheap labor in Mexico brought the total price of many goods down while enabling them to keep some production —and thus some economic benefit— in the United States.

This was crucial during the 2008 global recession. “Without the ability to move lower-wage jobs to Mexico,” one economist told The New York Times in March 2016, “we would have lost the whole [auto] industry.”

So lax labor standards in Mexico are indeed a problem with NAFTA. But they are North America’s problem to solve. With top trade officials reportedly sharply divided over what the goals of a renegotiated NAFTA should be, perhaps higher labor standards for all workers is something all three countries could agree on. At the very least, it would be a trade battle worth having.

***

Luis Gómez Romero is a senior Lecturer in Human Rights, Constitutional Law and Legal Theory at the University of Wollongong.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.