Originally published at Latin America News Dispatch.

Critics in Mexico had little use for Juan Rulfo’s novel when Pedro Páramo first appeared in 1955, and the slender volume that would become a national treasure sold poorly for its first four years. The critics questioned its central premise, the story of a man who walks into a village populated by talking ghosts. As the Mexican novelist and essayist Pedro Palou remarked last fall, “After such brutal reviews, I would have changed professions and become a street salesman.”

But Pedro Páramo and its author indeed gained wide acclaim throughout the Spanish-speaking world. Rulfo, who died in 1986 at the age of 69, is now considered one of the finest Latin American writers of the 20th century, even though only two works of fiction anchor his reputation, Pedro Páramo and his 1953 collection of short stories, El Llano en llamas (“The Burning Plain”). This past fall, critics and readers gathered in New York to honor the centennial of Rulfo’s birth in 1917 and, in the process, celebrated his achievements, debunked a few myths and pointed those who read in English toward the value of his work.

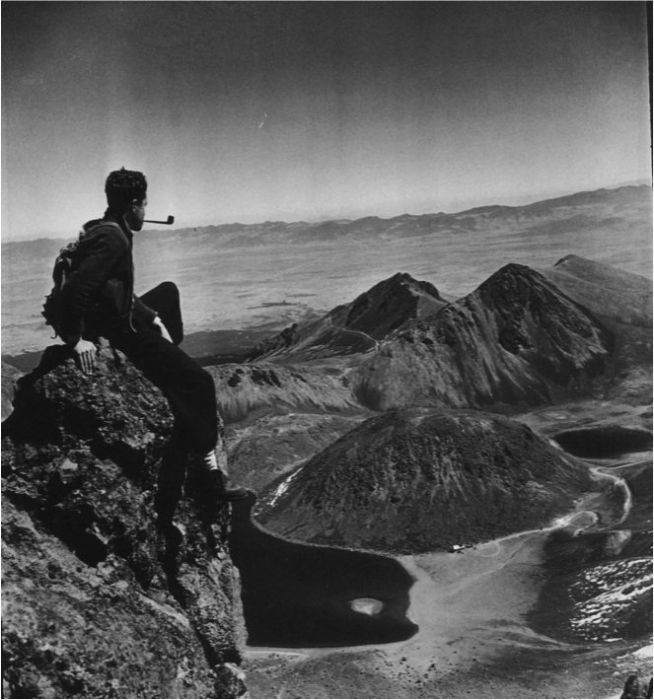

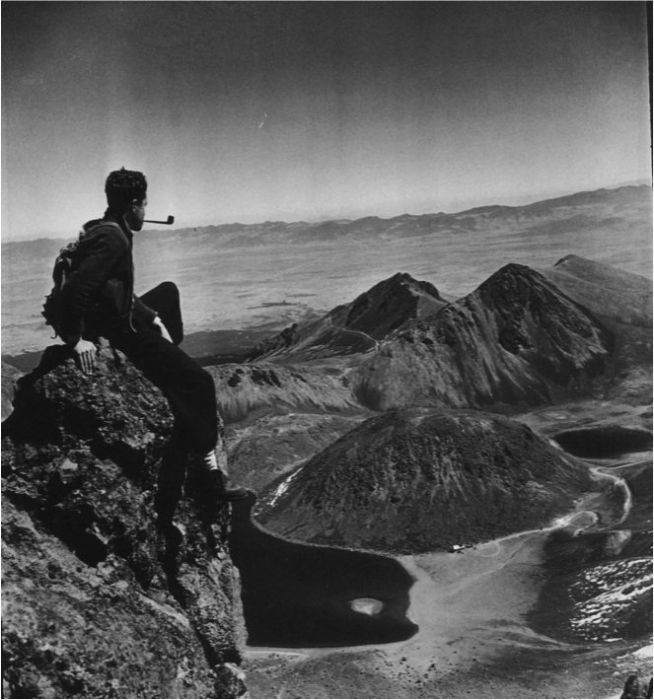

Juan Rulfo gazing at the horizon

It’s a bit of a mystery why Rulfo remains so unfamiliar in the United States compared with similarly popular Latin American authors who have managed to attract wide followings in English translation. A little unscientific experiment: At a general-themed bookstore in Manhattan, a stand displayed a collection of what the sign said were the “Must Owned Short Stories,” among which were works by Argentinian Jorge Luis Borges or Colombian Gabriel García Márquez, both major figures of the literary phenomenon known as the Latin American Boom. The effort required some ferreting, but LAND did find two of Rulfo’s books elsewhere in the store, however none of the store attendants was familiar with his work and only one employee, of Puerto Rican background, had ever heard his name.

Mary Louise Pratt, professor of comparative literature at New York University, considers Rulfo one of her “all-time most-revered writers,” one she teaches in many of her courses. “I wish he were recognized the way [Mexican authors Carlos] Fuentes and [Octavio] Paz are,” she said, “but anyone in the U.S. who knows Mexican literature at all knows Rulfo.”

Musicians in Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca, photographed by Rulfo in 1955

Palou ventured that the muted recognition of Rulfo’s work among U.S. readers might stem from deficient translations, but other experts, such as Cristina Rivera Garza, director of the doctoral program in creative writing in Spanish at the University of Houston, defended their quality and pointed elsewhere for explanations. “You’re right,” she said. “His work is not widely known in the U.S.,” she emailed in Spanish. “I could say that’s because the U.S. in general shies away from death-related themes—which are paramount throughout Rulfo’s work—but that would be too obvious.”

The preoccupation with death notwithstanding, Rulfo’s work is still very much alive. Cristina Rivera Garza recently published an homage to the late author, “Había mucha neblina o humo o no sé qué: Juan Rulfo, 100 años en llamas” (“There Was a Lot of Fog or Smoke or I Don’t Know What.”) “There is an active dialogue between Juan Rulfo’s work and the readers who also partake in Latin American literary traditions,” she said. “Rulfo still awakens all sort of passions.”

Rulfo, Mi último refugio

One of those passions revolves around what some critics have described as Rulfo’s “creative silence,” given that his two masterpieces were published just two years apart, and then nothing else appeared in print. Other experts question the very notion of “creative silence.” Palou addresses this in the book, The Burning Plain, Pedro Páramo and Other Works, a collection of essays on Rulfo by scholars from eight countries. Palou and others assert that Rulfo continued to think creatively but turned to other outlets of expression, such as writing film scripts and photography.

This facet of his life is explored in the docu-series One Hundred Years with Juan Rulfo, produced by his son, the prize-winning documentary filmmaker Juan Carlos Rulfo. In the film, which premiered in New York during the Celebrate Mexico Now Festival last October, researcher Paulina Millán traces Rulfo’s career as a photographer revealing that he shot photos even before he became a writer, starting as early as in 1932, and continued to shoot throughout a 30-year period.

In the film, Rulfo’s wife, Clara Aparicio, recalls how she met her future husband “with his Rolleiflex camera hung around his neck. You wouldn’t even notice when he was snapping pictures.” Rulfo traveled the meandering roads of rural Mexico taking pictures of hardy agaves puncturing clear skies, churches enveloped in mist and the everyday lives and festivities of peasants. The resulting images are evocative of scenes from his novel and short stories, photos of places that could easily be inhabited by his ethereal and otherworldly characters.

Juan Rulfo photo of dancer, 1960

It took involvement with the documentary for his son to arrive at another explanation for his father’s short bookshelf. As an author, Rulfo’s literary achievements never translated into riches. To feed his family of six required day jobs. Rulfo worked as a travel agent, a tire salesman and at what is now known as the Mexican National Commision for the Development of Indigenous Peoples. In an interview, Juan Carlos Rulfo posited that it may have simply been life’s exigencies that prevented his father from publishing more.

The documentary, in which Rulfo —the son— travels through Mexico in an attempt to retrace the exact locations where his father shot images, is an intimate and familial portrayal of the writer. The film is at times funny, but also permeated with nostalgia, as some of the places they are trying to recreate on tape decades after Rulfo’s death in 1986 are not quite the same as they were three decades years ago. Other sites have resisted the passage of time. “Yes, [I felt] a lot of nostalgia all the time,” Rulfo said. “Of course, because I miss my father. Sometimes you need somebody to be there just to give you a pat on the back and say you are doing okay.”

Rulfo and his son

All Image use authorized by Juan Carlos Rulfo.

***

Emily Corona is deputy editor of Latin American News Dispatch. She tweets from @daminijo.