Editor’s Note: Based on a compilation of true stories, where some of the names and scenes are changed, a version of this short story appeared in The Homeboy Review Issue 1 (Spring), 2009.

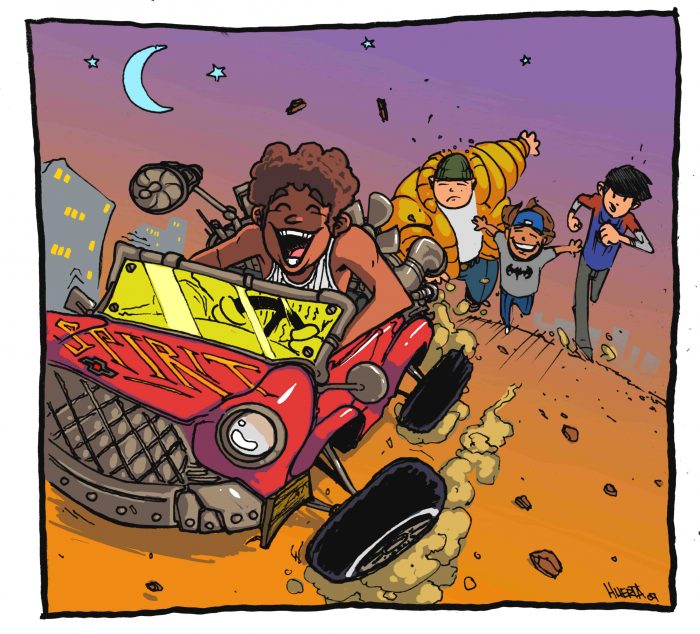

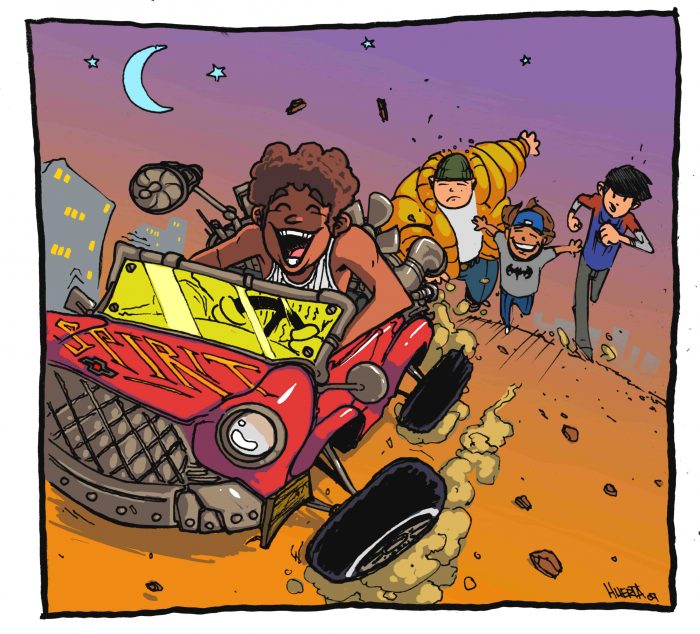

Cruising with Nayto (Image by Andrew Huerta, 2009)

Part I

I have always been nervous about visiting my old neighborhood.

One day, my brother Salomon —an acclaimed artist— invited my younger brothers (Noel and Ismael) and I to meet him at our old neighborhood, East Los Angeles’ notorious Ramona Gardens housing projects. (Apart from his good looks, Noel possessed the most talent and smarts among the brothers and in the projects.)

Salomon had to retouch his mural in memory of Arturo “Smokey” Jimenez, who was murdered by the cops in 1991. His killing sparked days of protests and riots from local residents against a long history of police brutality and harassment in America’s barrios.

Two days later, after receiving Salomon’s phone call, I drove my 1967 Mustang to the projects.

Many years had passed since I left the projects to attend UCLA, as a 17-year-old freshman—majoring in mathematics.

I always felt nervous about returning to my old neighborhood ever since, not knowing how my childhood friends and local homeboys would welcome me.

I abandoned them all: Buddy, Herby, Ivy, Chamino, Peanut Butter, Nayto, Teto, Tavo, Joaquin and Fat Ritchie. There is always a fat kid. I felt like I left them and my family in a hostile place. Together, we were safe. Separated, we became vulnerable.

My heart pounded as I approached the graffiti-decorated projects. I parked at the Shell gas station on Soto Street, near the 10 freeway. I looked at the rear-view mirror, as I combed my dark black hair with my Tres Flores hair gel and reminded myself that this is where I came from. Be tough, I thought to myself. I gained my composure and slowly mustered a tough demeanor. Signs of weakness only attract the bullies in the projects. I started my engine, cruised over the railroad tracks, slowed down for the speed bumps, passed the vacant Carnation factory and parked in front of La Paloma Market—where our family got credit.

As I got out of my car, not far from Smokey’s mural, a couple of homeboys confronted me.

“Where are you from, ese?” one of the homeboys asked, slowly approaching me. Actually, it was more of a demand.

“Hey, punk, what are you doing in the projects?” a young homebody chimed in. He must have been only 13 years of age, but was ready to defend his neighborhood. Sometimes, being tough is the only thing that a kid from the projects has to hold unto.

Before I could answer, a stocky homeboy replied, “Hey, man, leave him alone. I know this vato. We go way back.”

“Fat Ritchie, is that you?” I asked, relieved to be saved from the onslaught of blows that awaited me. There is something about pain that never appealed to me.

“That’s right,” he said, as he welcomed me with a bear hug.

“Hey, bro, how did you get so buff?” I asked, amazed at his transformation from the neighborhood fat kid to the muscular gangster. “Where do you work out? Gold’s Gym?”

“Nah, man, try San Quentin State Prison,” he proudly responded. “There’s no Gold’s Gym in Ramona Gardens!”

“Oh,” I said, feeling like an idiot for asking a stupid question. “By the way, have you seen Nayto?”

“I don’t know what happened to him,” Fat Ritchie responded. “Most of the guys we hung out with as kids are either dead, in jail, on drugs or got kicked out by the housing authorities. Only the dedicated ones stuck around to protect the neighborhood.”

As kids, we roamed the projects without paranoid parents dictating our every move. Life back then was not as violent. It was a time before crack, PCP and high-powered guns flowed into the projects without limits. While drugs and violence existed before the drug business skyrocketed and outsiders intervened in the projects, back then, problems among the homeboys usually resulted in a fistfight. And since no rival gang or outsider dared to venture into the projects, Ramona Gardens was our haven—except when it came to the cops or housing authorities (who behaved more like prison guards).

We were just a bunch of project kids hanging out, playing sports and getting into trouble. Every time we got into trouble, Nayto was in the middle of it.

There was something special about Nayto. He was tall and muscular for an eleven-year-old. He was dark-skinned with curly brown hair. He had great athletic skills that gained him respect among his peers. Despite his crooked teeth, he was always smiling. He seemed restless, always planning for his next scheme and adventure. Like many kids from the projects, he didn’t have a father in the household, making it difficult for his mother to keep track of him and his two younger brothers.

Reminiscing about Nayto takes me back to my childhood, when I played sports with my friends all day long. We liked playing baseball. It was a hot Sunday morning. We met, like always, in front of Murchison Street Elementary School. We had no parks in the projects, so we played on Murchison’s hot asphalt playground. We brought our cracked bats, old gloves, ripped baseballs and hand-me-down Dodger jerseys.

One by one, we scaled the school’s twelve-feet fence. Most of us climbed easily, like Marines performing boot camp drills. Yet, Fat Ritchie struggled. Like many other times, he found himself sitting on top of the fence, as Buddy shook it.

“Don’t mess around man,” Fat Ritchie pleaded with Buddy to stop.

“Hey, Buddy,” said Nayto, “leave him alone or else I’ll kick your ass, again.”

Once on the playground, we picked teams. Suddenly, Nayto ran off towards the school’s bungalows without saying a word. The game was not the same without Nayto. We would miss his home runs and wild curveballs. He would even nose dive like Pete Rose, when stealing second base. But, the game must go on, where we started to play without our best player.

Short a man, the team captains argued over the odd number of players to pick from. As a compromise, they decided that the team with less players got stuck with Fat Ritchie.

As the game began, we heard a noise coming from the janitor’s storage facility, adjacent to the empty bungalows with the broken windows.

“It’s just Nayto messing around,” yelled Joaquin from right field.

In the bottom of the third inning, Nayto finally emerged from the storage area. He ran across the playing ground with his clothes drenched in what appeared to be motor oil.

“Nobody say shit or else,” Nayto yelled, as he interrupted our game.

“What did he say?” asked Buddy.

“Nothing,” I replied. “Let’s keep playing, it’s just Nayto being Nayto.”

“Come on, let’s play,” said Herby. “I need to go home before I Love Lucy re-runs start.”

A few minutes later, a police helicopter appeared over the storage area. Five LAPD cars surrounded the school. Before we could run, the cops cut the lock on the fence and stormed the playground like a SWAT Team.

We knew the routine: we got down on our knees, put our hands behind the back of our heads and waited to be spoken to.

“Did you street punks see a dirty Mexican kid run through here a few minutes ago?” said a white cop. “He’s about five feet tall and full of oil.”

Following the neighborhood code, we stayed quiet in unison.

“Fine,” said the exasperated cop. “Clear this playground before I arrest all of you for trespassing.”

Frustrated, the cops drove away without knowing about Nayto’s whereabouts.

Pissed off, we slowly picked up our bats, gloves and balls to leave the school playground.

Out of nowhere, Nayto reappeared and ran towards the storage room, again. This time, he emerged carrying a large, oily item.

“Nayto ripped off Toney-the-Janitor,” said Fat Ritchie in a panic, while checking out the pillaged storage room.

We all ran home, before the cops returned.

Days later, as we played tackle football on the parking lot, Nayto cruised by in a gas-powered go-cart. We stopped our game and chased after him on our old bikes and skateboards.

It wasn’t your typical push-from-behind, wooden go-cart. It was a customized, low rider go-cart: painted cherry red, velvet seat covers, leather steering wheel and small whitewall tires with chrome-plated spoke rims. The engine was positioned in the back, like a VW Beatle. It had a Chevrolet emblem glued to the front.

It was a barrio gem!

“Where did you get that low rider go-cart?” I asked with envy.

“I made it myself,” Nayto said, not making a big fuss over his invention.

Aware of his tendency to lie, I closely examined the go-cart. The frame consisted of parts from Nayto’s old Schwinn bike. The seat —with the velvet upholstery— was a milk crate taken from La Paloma Market. And I will never forget the leather steering wheel, which Nayto took or borrowed from a stolen ’76 Cadillac El Dorado convertible that the homeboys abandoned in the projects. It still had the shiny Cadillac emblem in the center. In the front of the go-cart, the Chevrolet emblem also originated from a stolen car in the projects.

Once stripped by the homeboys, like a piñata at a kids party, the stolen car parts were up for grabs for the locals, prior to being torched.

The engine looked familiar, but I couldn’t figure out where Nayto got it from.

“Read what is says on the engine,” Nayto said, impatiently.

I took a second look at the oily engine. “Property of M.S.E.S?” I asked, not being able to decipher the acronym.

“I thought you were the smart one?” Nayto said with a smirk. “M.S.E.S. stands for Murchison Street Elementary School.”

“Oh, man!” I said. “You stole that… I mean… you got that from the storage room when the cops were looking for you the other day at Murchison.”

“Why do you think the school doesn’t clean the playground anymore?” he asked. “Do you remember that big vacuum cleaner that Toney-the-Janitor drove after school, while trying to hit us?”

“Yeah, that jerk hit me one time,” I said.

“I hated that man,” said Nayto. “That’s what he get for messing with us.”

“How about a ride?” I asked.

“Get on before the cops come by,” he replied.

We cruised around the projects in his customized, low rider go-cart, chasing down the little kids on their way to church and the winos in front of Food Gardens Market. Protecting their turf, the winos hurled empty Budweiser bottles at us, missing us by a mile. Unfazed, Nayto stepped on the pedal. Not paying attention, he ran over a cat. It belongs to Mother Rose, the only black lady left in the projects. Fearing Mother Rose’s wrath, he kept driving until we got drenched from the gushing water from the yellow fire hydrant on Crusado Lane.

Lacking a local pool, the homeboys would open the fire hydrant during hot days for the kids.

Driving for almost an hour, we ran out of gas. Luckily, Nayto was always prepared. He had a small water hose handy, where I volunteered to siphon gas from an old Toyota Pickup that belonged to Father John Santillan from Santa Teresita Church. Nayto claimed that he was once an altar boy, where Father John wouldn’t mind if we borrowed some gas.

Either way, there were some bad rumors in the neighborhood about Father John, so we didn’t consider it a sin.

Grateful for the ride, I siphoned the gas before the Sunday mass ended. The gas left a bad taste in my mouth. The Wrigley’s Spearmint gum that my father gave me later that day didn’t help. That adventurous ride, however, was worth every drop of gas that I consumed.

Those were the days…

***

Part II

The phone rang. It was 3:00 a.m. I slowly opened my eyes, taking a deep breath before I answered the call.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, knowing that good news never comes this early.

“Fat Ritchie passed away,” Buddy said. “The cops killed him, where witnesses said he was not armed.”

I hung up the phone. I felt numb. Another childhood friend was killed. When was this ever going to end, I wondered aloud?

Like most of the kids from the projects, from day one, Fat Ritchie never had a chance. He was a short, chubby kid who was constantly picked on by the neighborhood bullies. Whenever we played handball, one of the bullies would force him to stand against the wall until everyone had a chance to hit him with the ball. Once, while playing football at Murchison, the quarterback gave him the ball and everyone, including his teammates, dog piled on him until he couldn’t breathe. When he got up, everyone acted like they were innocent.

Since I last saw him, however, no one dared to pick on Fat Ritchie. Those who thrived in the penitentiary returned with a sense of respect and status.

While Fat Ritchie had earned the respect of the neighborhood, it was another story with the cops. Angry that they couldn’t bust him on a major crime, the cops falsely arrested Fat Ritchie for armed robbery based on the word of a local snitch. A couple of years later, upon his release, Fat Ritchie became another victim of police brutality.

Three days after receiving the tragic news, I returned to the projects to pay my last respects to Fat Ritchie. It was also an opportunity to reunite with my other childhood friends.

I arrived late. The church was full. I decided to wait outside with the other mourners, waiting for the coffin to be taken to the hearse.

Suddenly, I saw a tall homeboy with dark skin and curly brown hair carrying the coffin with three other homeboys. They’re all dressed in black with dark sun glasses.

“Is that Nayto?” I asked a stranger.

“What, ese?” he asked, sounding annoyed while he got closer to me.

“Back off, man,” I replied, letting him know that I, too, grew up the projects.

Once the homeboys gently placed the coffin inside the hearse, I walked towards the tall homeboy, as he made his way towards a 1967 Impala low rider. He got into his car and started the engine.

“Nayto, is that you?” I yelled out in his direction.

He glanced at me and, with without a word, drove away towards the cemetery.

A tear came down my cheek.

***

Dr. Alvaro Huerta is an assistant professor of urban and regional planning and ethnic and women’s studies at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. He is the author of Reframing the Latino Immigration Debate: Towards a Humanistic Paradigm (San Diego State University Press, 2013). As a scholar-activist, he primarily publishes scholarly books and journal articles, along with policy papers and social commentaries. Occasionally, while traveling and lecturing throughout the country, he writes short stories based on his childhood experiences in East Los Angeles. He holds a Ph.D. (city & regional planning) from UC Berkeley. He also holds a B.A. (history) and an M.A. (urban planning) from UCLA.