By Michael E. Lee, Fordham University

On March 24, 1980, the archbishop of San Salvador was shot inside his own church in a deliberate, cold-blooded murder that shocked the world.

Now, almost 40 years later, the Catholic Church is preparing to make the slain religious leader a saint. In early March, Pope Francis approved a miracle attributed to Monsignor Oscar Arnulfo Romero – the spontaneous healing of a woman in a coma—paving the way for his canonization.

Many Latin American Catholics thought this moment would never come. Romero was a human rights activist whose bold opposition to his country’s military dictatorship got him assassinated. The Vatican had stalled his canonization process for decades.

Why is Romero’s sainthood so controversial?

As I explore in my 2018 book, the archbishop’s defense of the poor challenged both El Salvador’s repressive government and the Catholic Church that stood by its side.

Liberation Theology

Under John Paul II, who was pope from 1978 to 2005, more saints were declared than under all previous popes combined.

But not Oscar Romero. His canonization process, which began in 1990, remained stuck at the Vatican for decades.

Most church observers agree that Romero was snubbed because of his association with a radical Catholic movement that emerged in Latin America in the 1970s called liberation theology. Its proponents claimed that salvation was not just something to be hoped for in the afterlife. Christians, they believed, should work today to make the world a better place.

Inspired by liberation theology, Latin Americans began rising up against military dictatorships, inequality, poverty and violence in the 1960s and 1970s .

Romero, a conservative Catholic when he was appointed archbishop of San Salvador in February 1977, ultimately became a symbol of this Christian commitment.

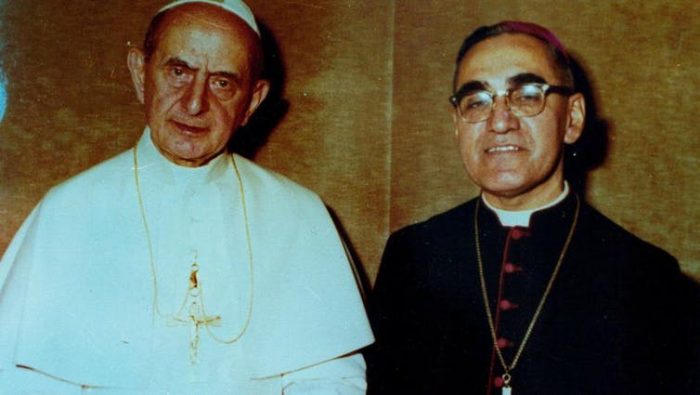

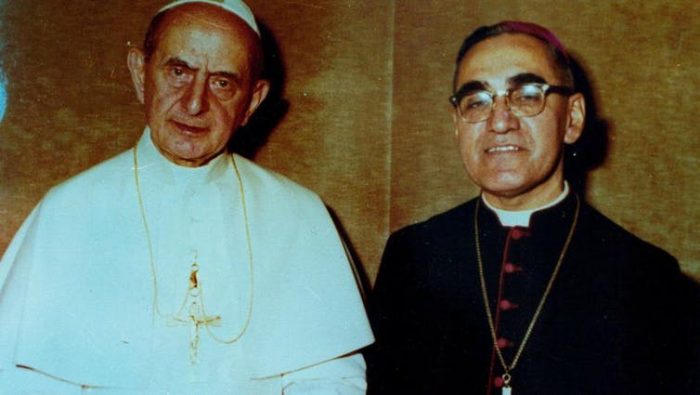

Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero and Pope Paul VI are expected be canonized together during the Synod of Bishops in October 2018 in Rome. (Arzobispado de San Salvador/Wikimedia Commons)

Voice of the Poor

By the late 1970s, the situation in El Salvador was rapidly deteriorating after decades of military rule.

Salvadorans, critical of an economy in which 8 percent of the population earned 50 percent of all national income, began marching on the streets and demanding equality. Protests were violently crushed. Dissidents began disappearing or turning up dead.

By the late 1970s, during the peak of the Cold War, guerrilla groups were calling for a revolution in El Salvador.

On March 12, 1977, the Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande —Romero’s friend and a leading figure of El Salvador’s progressive Catholics— was killed by a military death squad.

The incident seems to have triggered something in the once-conservative Romero. He began boycotting government ceremonies, saying police weren’t doing enough to investigate his fellow priest’s murder. In protest, he insisted that Grande’s funeral mass, on March 14, 1977, be the only mass celebrated in El Salvador that day.

For the next three years, Romero was among the loudest voices for justice in a country clearly headed toward civil war. That bloody 12-year conflict pitted the authoritarian, U.S.-backed government against the rebel forces of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front. At least 75,000 people were killed.

In weekly masses in the San Salvador cathedral, Romero would dedicate part of each Sunday’s service to discussing “the events of the day”—labor strikes, massacres and kidnappings. Because the government tightly controlled Salvadoran media, his sermons, which were broadcast nationwide on the radio, were a key source of news and information.

In 1980, Romero published an open letter to President Jimmy Carter demanding that the U.S. cease sending military aid to a government that killed its own citizens.

For his efforts, Salvadorans called Romero the “voice of the voiceless” and “journalist of the poor.”

Alienating Power

Romero’s affinity for liberation theology made the Catholic establishment suspicious. In their eyes, the Latin Americans challenging the status quo were inspired more by Karl Marx than by the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Public officials and social elites in El Salvador were dismayed, too. Even the U.S. State Department asked the Vatican to make Romero tone down his opposition.

Instead, in 1978, Romero founded Socorro Jurídico, a legal aid office that would go on to document hundreds of kidnappings, tortures and murders carried out by the Salvadoran armed forces and paramilitary troops.

On March 23, 1980, Romero concluded his Sunday sermon with an appeal to Salvadoran soldiers to cease killing their fellow citizens.

“Les suplico, les ruego, les ordeno en nombre de Dios: Cese la represión!” he cried to a frenzied ovation in the cathedral. “I beg you, in the name of God, stop the repression!”

He was killed the next day. The murder remains unsolved.

Almost 15 years later, when a peace agreement ended the violence, Socorro Jurídico was a key source for the United Nations Truth Commission’s report on the Salvadoran civil war.

Salvadoran guerrilla forces in the Morazán department of El Salvador in 1990, two years before the end of a civil war that would kill 75,000 people. (Linda Hess Miller, CC BY)

Conflict Over Martyr Status

When Romero is canonized, which is likely to occur in October in Rome, he will become the first Central America-born figure given that honor.

The Vatican recognizes two kinds of saints: “confessors,” who lived virtuously, and “martyrs.” Catholic martyrs must meet three criteria. They must have suffered a cruel or violent death and freely accepted that death. That death must also be an act of hatred against Catholicism – “odium fidei,” in Latin.

Pope Francis’s decision to recognize Romero as a martyr troubles some Vatican officials, who believe Romero was killed for his leftist politics. Supporters of his canonization argue that Romero’s human rights work flowed from his faith.

The Catholic Church has previously recognized martyrs murdered under similarly unclear circumstances, including the Polish priest Maximilian Kolbe, who volunteered to die in place of another captive at the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Recognizing Romero as a martyr–saint opens the door for the canonization of other slain Latin American bishops. Top in line are Enrique Angelelli, assassinated in 1976 during Argentina’s military dictatorship, and the Guatemalan Juan Jose Gerardi, who was beaten to death in 1998, two days after publishing a chronicle of his own country’s bloody civil war.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.