The Department of Commerce under the Trump Administration announced on Monday that the upcoming 2020 Census will ask us about citizenship status. At least 12 states are filing a lawsuit to leave the question off the 2020 census.

Many white media commentators, such as those from Vox and CNN, reported concerns that authorized and unauthorized immigrants will skip the question out of fear that the information could be used against them. This could possibly lead to blue states with large number of immigrants (like New York and California) will have fewer reported people in a Census that will ultimately determine their number of congressional representatives.

Immigrants, and immigrants of color especially, must carefully weigh if the benefit to submit their Census forms outweighs the risk of using the information against them. To be counted or not to be counted is intertwined with a complicated history of the Census and people of color.

Let me start by telling my own story of the Census. In 2010, I was living in our New York City suburb with my then-fiancé and now-husband, a Peruvian immigrant raised in Mexico. After receiving the forms, we debated: Should we fill it out?

My partner was skeptical to provide basic information to the government. At the time, he was a visa-holding immigrant who desired to stay in the country permanently one day. His fear was due to the anti-immigrant policies that were proliferating during the Great Recession in 2010—such as Obama’s exploding deportation numbers and Arizona’s “Papers Please” law. Hence, he was especially concerned about the government’s use of his information against him because of his immigration status which was authorized but subject to the whims of the government.

I was skeptical too. As a citizen of color and a data analyst by training, I understood the importance of my demographic information for the Census. I was more concerned about how two additional Latino bodies would impact gerrymandering and appropriation of representatives in Congress. Until 2008 with the election of Democrat Jim Himes, the district that I lived in was the only Republican district in the Northeast. Disgusted by Tea Party politics and Republicans’ “Papers Please” law, I did not want my Census forms to contribute to more people of color to a white, wealthy district that could easily swing back to red.

In the end, we submitted it on the day of deadline.

So what’s the big deal to submit a 10-item questionnaire to the government? To answer this question requires an explanation about the complicated history of the Census for people of color.

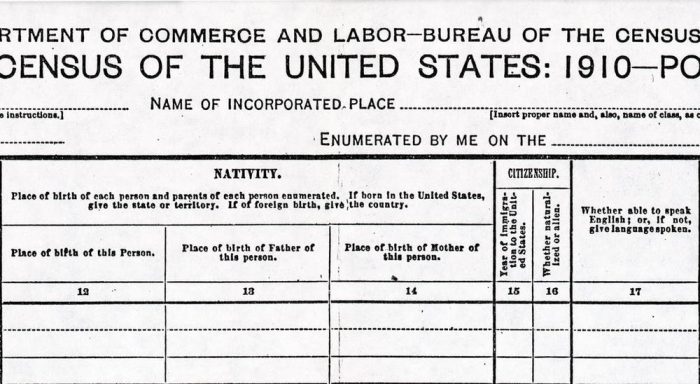

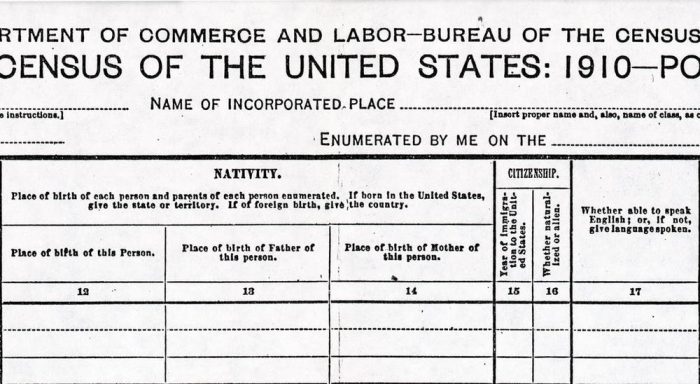

A 1910 census population schedule. (U.S. Census Bureau)

1787: The Constitution and the Three-Fifths Compromise

We can start to trace this history at the founding of our country. Article I, Section 2, of the U.S. Constitution of 1787 was written as follows:

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

In other words, black slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person. Untaxed Native Americans were excluded from the counts altogether.

The 1930s: The Census, Japanese Internment and the Mexican Category

In the 1930s, the Census captured information on Japanese ethnicity. It was revealed in 2000 that the Census provided the U.S. Secret Service with names and addresses of Japanese-Americans during World War II. This allowed the Secret Service to round them up and place them in internment camps.

In 1930, due to the massive immigration from Mexico in the preceding two decades, Census bureaucrats (supported by white politicians) decided to create a category to count the number of individuals with Mexican ancestry. Historians found that the Mexican category was not created on the basis to authentically represent those with Mexican ancestry. Instead, its creation came from a desire to count Mexicans separate from whites, because eugenicists in government thought Mexicans were genetically and culturally inferior to white Americans. In the 1930s, LULAC challenged the creation of the Mexican category because they argued that Mexicans were whites and abandoned their Mexican ethnicity after immigrating to the United States. LULAC prevailed.

The 1970s: Latino Activists and the Hispanic Box

The 1930s category returned with the 1970 Census, but this time, it returned as the catch-all category “Hispanic.” Unlike the 1930 Census that included Mexican ethnicity due to white supremacy from racist bureaucrats, the 1970 Census was a direct result of organizing within the Latino community. G. Cristina Mora’s 2014 book Making Hispanics argues that Latino activists pressured the Census to create the Hispanic category, because Latino/Hispanics were being captured under the white box in Census. Latinos’ classification as “white” impeded activists from depicting Hispanics/Latinos as underrepresented minorities. This construction transformed a group of people who somewhat shared a language and geography but from different countries into a shared ethnicity.

The 1990s: Census Projections of Latino Numbers and Social Policy

In the 1990s, the Census started to release projections of how the Latino/Hispanic community was going to explode in count. It should be noted that the Census was getting better at accurately counting the community. They were making their forms available in Spanish, was better at finding Hispanics/Latinos respondents, and included the Hispanic ethnicity box.

Academics and media were framing these increasing Census projections as “making whites the minority” in places like California. Mainstream media, such as The New York Times, were stating that Hispanic/Latino increasing numbers will outnumber African Americans. In essence, these frames set up the idea that this country will no longer be majority white and that minorities will be mostly brown.

The population explosion projected by Census led to white anxiety that helped to institute policies to limit Latino/Hispanic access. Census projected Texas and California to see the largest increases of the Latino population. These were also the first states to do sweeping reversals of Affirmative Action policies. Californians voted in Proposition 209 that reversed affirmative action in their public universities. The case of Hopwood v Texas led to the elimination of the use of race for admissions. (Although that has changed since.)

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 created the fences along the Mexican-U.S. border. It allowed unauthorized immigrants who were in the country to be banned from reentry for up to 10 years. Most importantly, it facilitated the explosion of detention centers since now local police could work with federal agents to report unauthorized immigrants. The Census and their projections of a Latino minority-majority helped to fuel anti-Latino immigrant sentiment and policies that continue to this day.

While the Census may seem like a piece of paper just to submit, this piece traces how the Census has been weaponized against people of color—in particular, Latinos/Hispanics. Even today, we had to deal with misinformed journalists and commentators seeing us as the “new Italians” since 7% of Latinos switched their racial identity from “some other race” to white (yes, you Nate Cohn).

Not Just a Piece of Paper

The Census is a big deal. It is used to determine policies from district boundaries for representation to congress to decisions about public infrastructure such as schools and roads. Now that the Census under the Trump Administration wants to add a question about citizenship. They run the risk that people like my immigrant husband not responding or angering citizens of color like myself responding altogether as a political statement.

More than anything, we would not even have a chance to be counted as three-fifths of a person in the U.S., but not to be counted as a person at all.

***

Christina Saenz can be reached @incatekmom.