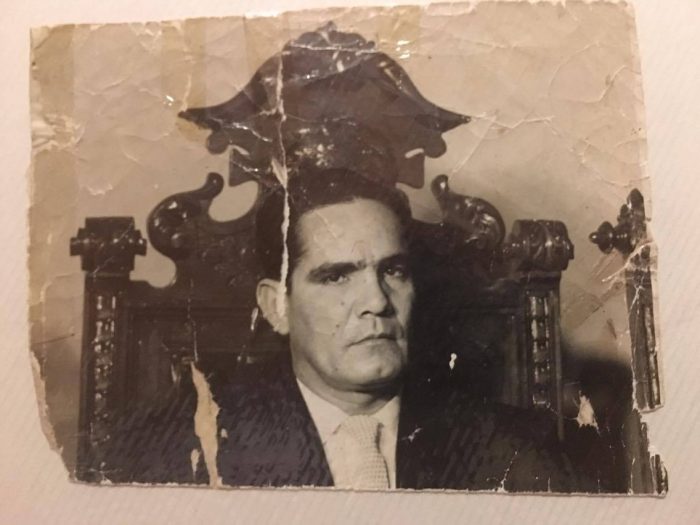

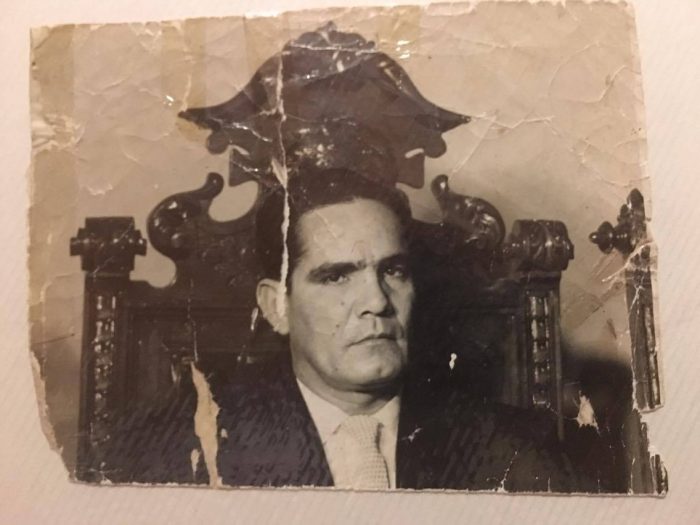

Jesús De Loera-López (Photo provided by the author)

I never met my grandfather, my dad’s dad. His name was Jesús De Loera-López and he was a Bracero, one of between anywhere from two to four million men brought from Mexico by the U.S government between 1942 and 1964, largely to be farmworkers in American agriculture. From a young age, I learned his story from my own dad and internalized the moral of the story: the hands that pick the crops are the hands we all depend on. I was taught always to be full of respect and gratitude for the people who work the fields.

The Braceros shaped the American West. California, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington especially have been shaped by their legacy. Without them, American agriculture would have collapsed. Braceros were needed to replace the men who went off the World War II. When the soldiers and sailors came back, most of the white ones got housing loans and the G.I. Bill and an easy boost into the American middle class. American agriculture in the West had already depended on Mexican and other immigrant farmworkers before the war too, but after a majority of white Americans got a taste of the middle class, there was no hope of breaking agriculture’s addiction to Mexican hands.

The Catholic Church in Mexico was against the Bracero program. Mexican church leaders feared what would happen to the stability of Mexican families if the men headed north for months at a time. The church worried that the men would fall into alcoholism, gambling, or adultery while gone. They worried that American Protestant missionaries would get to the Braceros and turn them from the true faith. They even worried that perhaps if Mexican men got a taste of better wages up north, they might come down and demand more, shaking the fragile social order the Mexican Church depended on. From the pulpit, priests and bishops urged Mexicans not to go.

Nevertheless, the Braceros signed up. There were good jobs up north. The Braceros were offered decent conditions in migrant camps, 30 cents an hour, and were promised they wouldn’t be subject to discrimination. Often these were lies. That last one was always a lie.

Throughout the 40s there were Bracero strikes across the West. There were some successes. But most times strikes were broken, and ringleaders deported. Woody Guthrie wrote a song about Bracero deportees, specifically the time when a plane carrying dozens of them crashed. That’s all many Americans know of it.

I wonder often if my grandfather heard of any of these strikes? He was a Bracero from 1945-1949. He worked from Arizona to Minnesota, in the fields, and also on the railroads, laying down the track that would enable harvests to be whisked away to market. When he returned to Mexico, my grandfather went into politics. I wonder if he did not learn some politics in the fields of the American West, perhaps from a strike against some American landowner now lost to history. Perhaps he learned from some older Braceros who themselves might have been old enough to remember the revolutionary days of Zapata and Pancho Villa. I’m allowed to dream.

My grandpa was sprayed with DDT when he crossed the border to begin his time as a Bracero. That was standard procedure. All Braceros removed their shirts and were sprayed in masse with DDT by Department of Agriculture personnel as they entered the United States. Someone, somewhere had raised the concern that the Braceros would surely bring lice and disease. Best to spray them when they came in just to be safe. To be fair, no one knew DDT was a carcinogen at the time.

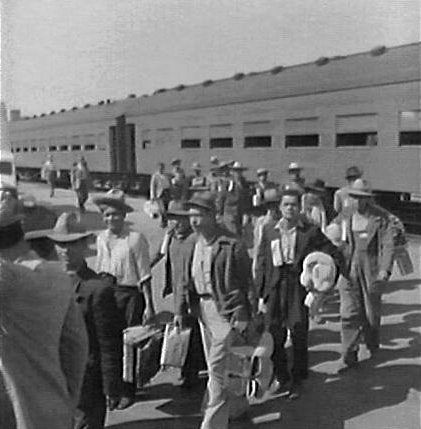

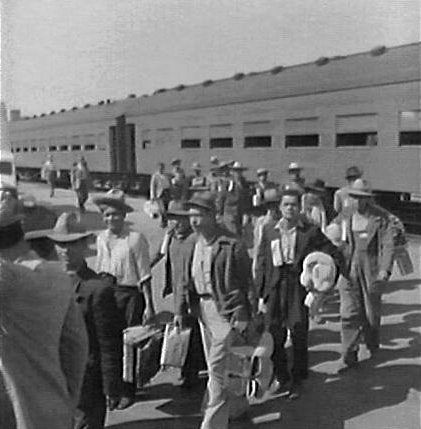

Mexican workers undergoing inspection at U.S. border (Public Domain)

The Bracero program never admitted every Mexican who wanted a job. But thanks to the program, every Mexican knew how much money could be made working up north for a season. Many Mexicans did what anyone would have done and hopped the border. By the early 50s, concern over illegal immigration had increased. The Eisenhower administration authorized “Operation Wetback” in response. Almost a million Mexican-origin people were rounded up, packed onto box cars and cargo ships and shipped deep into Mexico, far from the border. Some estimate as many as half were U.S. citizens.

The Bracero program ended in 1964. The stated goal was to lift the wages of American workers. César Chávez himself, founder of the United Farm Workers, was against the Bracero program, fearing that as long as the growers could import the labor they needed, organizing a farmworker strike was impossible. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson similarly were concerned about the well-being of U.S.-born farmworkers. Nevertheless, it must be noted the Department of Labor Commission, whose study convinced Kennedy and Johnson to end the program, was led by a eugenicist who believed Mexicans were a genetically-inferior race.

Economists have used the end of the Bracero program to study what effect the sudden disappearance of foreign workers might have on the wages of the native-born. They found no significant change in wages for farmworkers. Instead, growers in California turned for the first time to automation, foreshadowing disruptions of the labor market still to come. And undocumented immigration increased, following the trail to higher paying jobs the Bracero program had blazed. In the decades that followed, millions of Mexican immigrants would come following the footsteps of the Braceros, aware that the American economy still needed them, regardless of what American law pretended.

Our immigration politics have changed dramatically since the end of the Bracero program. Today, Mexican migration is at net neutral or even negative—for the first time in generations. A wall now sits at the border, and crossing it is now a grueling and life threatening trek through a desert populated by snakes, patrolled by drones, and infested with racists. Ironically, this only increased the undocumented population of the United States. In millions of painful individual decisions, most undocumented Mexican immigrants decided that, rather than risk capture with seasonal crossings, they should bring their families with them and settle for good. Today we debate the future of the children that last great wave of Mexican immigrants carried with them. We call them Dreamers, but they are hostages; the main political question now is who or what will be sacrificed in exchange?

Braceros arriving in Los Angeles (Public domain)

The President’s position has been that in exchange for the hostages he alternates between “loving” and demonizing, he wants a “merit-based” immigration system. I wonder what “merit-based” means. They say it means wanting to attract more “skilled” immigrants. But by “skilled” they mean people with college educations (or maybe just Norwegians). By “skilled” they mean people like my grandfather’s son, my father, who came here on a student visa and is now a tenured professor of mathematics, at UC Davis no less (where many of the machines that replaced the Braceros in the 1960s were developed). Certainly, math is a skill. But so is being able to work 16-hour days with your back bent down, pulling out food we eat from its home in the dirt under the summer sun.

That is certainly a skill I don’t have. Nor is it a skill most of my friends have. I remember a white high school peer complaining to me once he was unemployed. I suggested I could easily get him a job in the tomato fields. He told me to stop joking. But my grandpa had the skill to do it; the skill of being “unskilled.” In a time of war, and even after, this country begged him, and millions like him, to come, only to one day pretend like it had never wanted any Mexicans at all.

“Mexican workers await legal employment in the United States,” Mexicali, 1954 (Public Domain)

Today, farmworkers are once again in high demand with too low a supply. The farmworkers the growers once feared losing to Chávez’ strikes are now being lost to ICE raids. The growers, who mostly supported President Trump, are now panicking as they face the prospect of their crops rotting with no one to pick them. It would make me laugh if farmworker families were not being destroyed. The stolen land itself is feeling the repercussions of the lack of labor. California farmers, even in the midst of drought, have been planting water-intensive almond trees, as almonds require less labor to pick than grapes or tomatoes. So much water is being pumped out of the ground, that there are parts of the Central Valley that sink by a foot or more a year. Such are the butterfly effects of our immigration politics.

My grandpa died in the 1970s. My grandmother, who remains convinced that my grandfather could have become the Governor of Coahuila had he only been willing to pay the right bribe, once told me a story that implied that perhaps it was his political enemies who poisoned him. My father however, the most reliable source, told me that my grandfather died of complications from diabetes. The body that worked the fields broke down over its inability to process sugar. Diabetes is a genetic disease; my father has diabetes too, and I know that my father tells me the story as a warning for my own health. “Come bien,” my dad tells me. Sure enough, there are always vegetables on the shelves for me to buy, thanks to the farmworkers who pick them of course though they themselves often cannot afford to buy them.

I do not believe the DDT my grandfather was sprayed with had anything to do with my Bracero grandfather’s premature death. But then again I can’t really be sure, can I? And when I drive by the fields of Central California and see the yellow crop duster release it’s payload of pesticides over a field on a windy day, I wonder if it perhaps was our enemies who poisoned him and who have indeed poisoned many others.

In 2014, I was recruiting volunteers for the afterschool program I was running at one of the local farmworker camps. Most of the farmworkers who were there were from Mexico, here on H2-A visas, the contemporary guest worker program. But let’s not make it too complicated. The people who feed us are people we have a debt to. The least we could do is make sure their kids are properly looked after while their parents worked in the fields. That’s what the program I ran set out to do.

There was a really nice and eager white girl who was excited to come out to help and we were excited to have her. But shortly before the start of the summer we learned she couldn’t come out after all. Her mother had forbidden it. She was concerned the migrant kids were carrying lice.

There’s still work to be done.

***

Antonio De Loera-Brust is a Mexican-American writer and filmmaker from Davis, California. He has a degree in film production and Chicana/o studies from Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. He was a Joseph A. O’Hare S.J. fellow at America Magazine, based in New York City. He is a U.S. politics and international soccer junkie. He loves tacos, history, and the outdoors, and writes about diversity, farmworkers, and politics. You can follow him on Twitter @AntonioDeLoeraB.