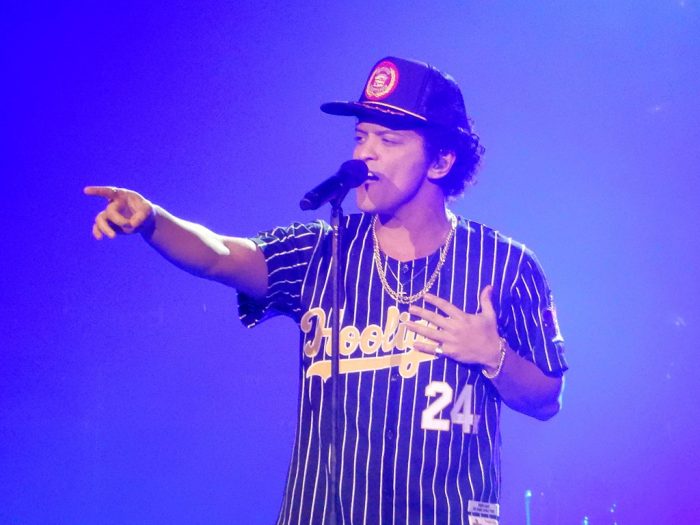

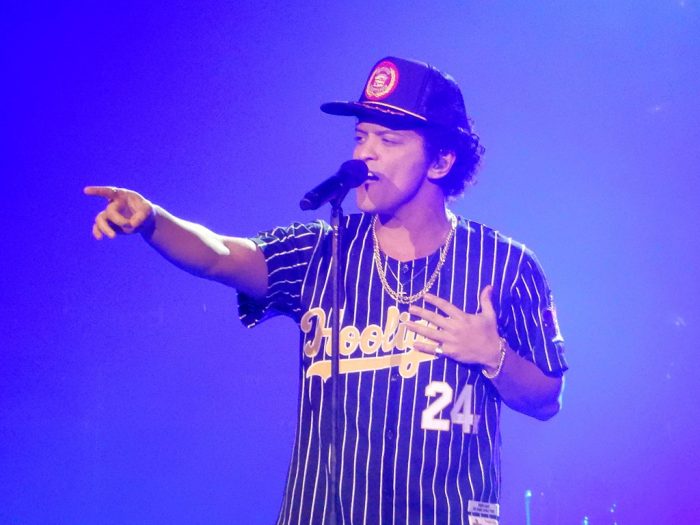

Bruno Mars in 2017 (Photo by slgckgc/Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license)

Just as many predicted after Bruno Mars won Album of the Year at this year’s Grammys, the cultural appropriation debate made the rounds again on Twitter last month (this isn’t a new debate). This time it was a video that went viral where a young woman, Seren Sensei, offered several reasons for considering Mars a cultural appropriator who doesn’t deserve the accolades he’s received. Sensei juxtaposed Mars to Michael Jackson and Prince, labeling them as originators and Mars as a “karaoke singer” who “takes pre-existing work and word-for-word recreates it.” The crux of her argument was that Black artists haven’t received similar accolades (Prince, for example, never won Album of the Year), and that mainstream America only wants to consume Black music if it’s performed by a non-Black body.

this is why i hate bruno mars @seren_sensei says it all pic.twitter.com/CRLktsA2ea

— hannie (@hannahmburrell) March 9, 2018

As quite a few cultural critics have argued (for example), appropriation isn’t as simple or objective a matter as Sensei presented it. While there is a long history of appropriation (and theft) of Black music by white artists that has not only moral, but economic implications, serious debates on this issue have to account for the contemporary context. This is not the 1950s, when Black artists like Big Mama Thornton (whose version of “Hound Dog” preceded Elvis’s vastly more famous and profitable version) were prevented from receiving mainstream airplay because of a segregated music industry and the phenomenon of “race records”. The most dominant pop music artist of our time is Beyoncé, and the past two years have seen other Black artists (Diddy, Jay-Z, Drake, Rihanna, The Weeknd) at the top of the highest paid musicians list.

Beyond not accounting for the economic success of contemporary Black artists, Sensei’s characterization of Mars’s music as derivative is bizarre. Not only does he not sing versions of other artists’ songs, but he’s an incredibly talented songwriter who has also written music for other major pop stars. Even presenting a dichotomy between “original” and “derivative” artists is problematic. Yes, Bruno Mars draws on past styles for inspiration—just like all musicians do. There’s no such thing as pure, unadulterated originality. Every innovation is a product of past genres and styles, including those of Prince, Michael Jackson, and even the most celebrated composers in the western world: Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven. Prince was undoubtedly a musical genius, but that doesn’t mean his music sprang from his head completely unsullied by previous styles.

A nuanced discussion of cultural appropriation should revolve around the specific ways artists engage with Black music instead of only the artists’ race. George Michael, Bobby Caldwell, Hall and Oates, Teena Marie, and other “blue-eyed soul” artists are generally thought of not as appropriators, but as respectfully engaging with Black music and performing it well. This can be contrasted with white artists who “dip their toes into Black music” because it’s trendy (hello Taylor, Miley, and Katy), or who don’t give credit to their Black influences. Bruno Mars just doesn’t fit into this category, and he’s got the receipts to prove it.

Whether non-Black artists of color can be labeled cultural appropriators is up for debate, but the case of Bruno Mars is particularly messy. Sensei’s statement that Mars is “not Black at all” ignores the fact that he is a quarter Puerto Rican, and the island has a significant population of African descent. Mars himself pointed out the African roots of salsa, so he no doubt understands the racial implications of his ancestry.

Given the pervasiveness of racial mixture in the Caribbean, it’s likely that Mars’s DNA profile would show some degree of African ancestry. What amount of African ancestry qualifies for one not to be labeled a cultural appropriator? This silly question betrays the ultimate futility of judging cultural appropriation solely based on an artist’s race, as most artists who identify as Black (indeed, most Black people in the Americas) are actually racially mixed in terms of their DNA.

While I don’t want to argue that Mars’s Puerto Rican heritage and probable African ancestry is the reason we shouldn’t call him a cultural appropriator, it’s notable that so few people weighing in on this debate even recognized Puerto Rico as a site of the African diaspora. This is, I believe, because Afro-Latinx people continue to be invisible in the United States, even among Black Americans.

The recent emergence of celebrities who identify as Afro-Latinx (Amara La Negra, Zoe Saldana, Miguel) is beginning to shift the discussion about race and Latinidad. However, many Americans still view the term “Latino” as a racial, not ethnic, identifier, and don’t understand that Latinx can be Black, white, indigenous, or racially mixed. The misconception that Latinx make up one huge racial group and don’t experience racial disparities just like non-Latinx do is still widely held. And, just as in Latin America, Black people are the least visible sector of the U.S. Latinx population. This, despite the fact that roughly a quarter of U.S. Latinx identify as Afro-Latino.

Consider Netflix’s One Day At A Time, considered to be one of the best shows about the Latinx experience on TV right now. And yet, despite tackling a wide range of issues in an incredibly heartfelt and funny way, it still renders Afro-Latinx somewhat invisible. In a recent episode, family matriarch Lydia (played by the incomparable Rita Moreno) repeatedly insists that Cubans are white, mostly descended from white Spaniards. While her daughter Penelope challenges this myth, ultimately Lydia gets the last word in: Penelope states, “Saying we’re white, brown, Black, that’s beside the point,” to which Lydia responds, “Exactly!” and then whispers to granddaughter Elena, “we are white.”

So, while the episode acknowledges the different skin colors of siblings Elena and Alex —and Elena realizes that she’s a “white-passing” Latinx— ultimately it sends the message that all Cubans are white and racial differences among them don’t matter. It is exactly this type of erasure of blackness and racial difference that’s highlighted in a one-liner by Juan (played by Mahershala Ali) in Barry Jenkins’s sublime Oscar-winning movie Moonlight: “Lotta Black folks in Cuba but you wouldn’t know it from being here [in Miami].”

In reality, racial differences among Latinx aren’t “beside the point,” because they have tangible consequences in a country and world still plagued by systemic racism. Black Latinx face the same marginalization as African Americans with regards to skin color, although the latter don’t always acknowledge this and sometimes engage in gatekeeping that excludes Afro-Latinx. Conversely, there are fair-skinned Latinx who enjoy the benefits of white privilege, particularly if they were born in the U.S. and speak English fluently. Thus, the recent emergence of the term “white-passing Latinx.” While the term recognizes that not all Latinx face the same degree of marginalization, it still clings to the idea that “Latino” is a term denoting one’s race: we wouldn’t need to call someone “white-passing” if we simply acknowledged their whiteness and that one can be both white and Latinx.

The acknowledgement of racial difference within Latin America and among U.S. Latinx is a sensitive topic that challenges long-held national myths regarding the absence of racism in Latin America; Latin Americans often insist they can’t be racist because “everyone is mixed.” Yet Black, indigenous, and dark-skinned Latin Americans are disproportionately poor, incarcerated, and/or underrepresented in positions of power, not to mention the continued valorization of European ideals of beauty.

So what does all this say about Bruno Mars and cultural appropriation? Again, by highlighting his connection to the African diaspora by way of Puerto Rico, I don’t want to suggest these debates can be resolved through a DNA test, or that there’s no such thing as harmful appropriation. Instead, I want to emphasize, like Mars did in a 2017 interview with Latina magazine, that Black music and identity don’t stop at the U.S. border, but instead extend to the whole African diaspora, including Latin America.

It’s not only “non-Black” artists who have borrowed from Black American styles; African American musicians have also been inspired by styles not born in the U.S. Hip hop, for example, wouldn’t exist without Jamaican dancehall (not to mention the role of Puerto Ricans as early break dancers), and early jazz musicians in New Orleans were influenced by late nineteenth century Cuban styles. What simplistic debates about appropriation miss is that cultural exchange rarely goes in only one direction. The Afro-Cuban jazz movement of the 1940s—which saw collaborations between Black Cuban musicians like Chano Pozo and famed jazz musicians like Dizzy Gillespie—effectively birthed a new genre, Latin jazz. In other words, Afro-Latino cultures and musicians have contributed in major ways to popular music in the U.S.—whether in the form of salsa, merengue, reggaetón, bachata, or jazz. It’s time they enjoyed some recognition for this and that the term “Black music” expanded to include them.

***

Based in Oakland, Rebecca Bodenheimer is a writer and independent scholar. She focuses on pop culture (music, TV, film), Cuba, identity politics (race, gender, fat phobia), higher education and media representation. Rebecca tweets from @rmbodenheimer.