By Emmanuel Estrada López y Maricelis Rivera Santos | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

(Photo by the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo)

Spanish version here.

For the past eight years, Puerto Rico has faced at least one extreme event every year. Hurricanes, droughts and floods have landed multimillion dollar blows to the island, while 92% of coastal towns have suffered from beach erosion.

The Puerto Rico government has known for years about the serious threat facing the island. Under the administration of the two political parties that have been in office since 2005, the Legislature and the Executive branch have enacted a total of 62 measures to tackle climate change and its effects on the island. None has translated into action, according to an investigation by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI).

Extreme events, meanwhile, will have cost $144 billion during the past 20 years —an amount that mirrors Puerto Rico’s public debt, when including pension obligations— according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Puerto Rico State Agency for Emergency and Disaster Management (Aemead).

The most recent measure to “address concerns related to climate change,” Senate Bill 773, was filed in December by Lawrence Seilhamer, a New Progressive Party (PNP) senator who endorsed repealing the only law that has been enacted on the matter, Act 246 of 2008. The latter, signed by Popular Democratic Party (PPD) Gov. Aníbal Acevedo Vilá, called for the creation of an independent body, the Committee of Experts on Climate Change, which would come up with a Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change Plan for Puerto Rico. Two years later, however, the Senate voted unanimously to eliminate the committee, without its provisions being put into effect.

Seilhamer now proposes a bill with largely the same elements that were in the law that was repealed a decade ago. Several experts agreed that his proposal fails to address key issues related to climate change and that have affected Puerto Rico during the past decade, such as beach erosion. The experts added it fails to provide the most important solution: an adaptation plan to reduce the population’s vulnerability to the effects that are already affecting the island.

Senate Bill 773 also calls for measures related to renewable energy that seem unlikely, based on the island’s historical experience of noncompliance to this end. The existing goal is 12% of energy produced by renewables by 2019; it reaches only 2% to 4% to date. The PNP lawmaker is pushing for an increase of that goal to 33% by 2035.

Seilhamer justified the contradiction of his legislative record by arguing that, over time, he has been educated about climate change and has seen its effects.

“I didn’t think in 2009 the same way I do today. There are some signals being sent to us that we cannot ignore,” he told the CPI.

“I have no problem whatsoever in saying that the issue of climate change is one that I have been educated about. Because nature is showing clear and forceful signals, and it would border on negligence if it is not taken care of,” he added.

Lawrence Seilhamer (center right) talking with Puerto Rico governor Pedro Rosselló Nevares (center left) last year in San Juan. (Photo via La Fortaleza)

Seilhamer, nevertheless, admitted there is no sense of urgency in addressing this issue among Puerto Rico lawmakers.

Nor does there seem to be a sense of urgency from governor Ricardo Rosselló Nevares, who has only devoted a few words to the issue of climate change since Hurricane María. In sum, the governor has stated he would support related legislative measures.

“I’m the bill’s sponsor, but I recognize the work of the Puerto Rico Climate Change Council of Puerto Rico, of senator Cirilo Tirado Rivera, who has introduced bills but has not received the support of either his [PDP] administration or mine. So in that scenario, it seems that this Senate, this House of Representatives and this government administration will have the responsibility to face the people, because I can assure you this will get worse, that there will be more frequency of atmospheric phenomena that will also be more powerful and we have to prepare,” Seilhamer said.

Before Rosselló Nevares entered office, his predecessor, Alejandro García Padilla, also ordered the commonwealth’s environmental and infrastructure agencies to draft adaptation plans through executive order OE-2013-16. But the past administration failed to come up with these plans, the CPI found, as only three of 15 agencies delivered their respective plans.

Meanwhile, the Puerto Rico Council on Climate Change (CCCPR by its Spanish initials) —an independent organization that comprises 150 scientists, who study the risks and impact of climate change on the island and recommend public policy to this end— have estimated that roughly 500,000 people live areas prone to flooding due to overflow of rivers and streams, while some 100,000 are vulnerable to floods as a result of storm surges, explained Ernesto Díaz, coordinator of the CCCPR and Coastal Zone Management director at the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DRNA by its Spanish initials).

In their recent review of the flood zone map, the Puerto Rico Planning Board, together with FEMA, estimated that 252,748 structures throughout the island face the risk of flooding.

Loíza, Puerto Rico after Hurricane María (Photo by Centro de Periodismo Investigativo)

The effects of climate change in Puerto Rico have been documented in multiple studies carried out by local scientists, who affirm that every government administration has ignored these analyses, which are vital for the preparation of an adaptation plan. Such effects have begun to impact the local tourism industry with beach erosion and the related loss of properties in places such as Rincón and Isabela. Tourism is one of the sectors in which the government has pinned its hopes for sparking the local economy, which has lingered in recession for more than a decade. For 2016, tourism represented 8% of Puerto Rico’s gross domestic product, or $8.4 billion out of $105 billion, according to the Industrial Development Corp.

Additionally, there is the fear among people from rich and poor communities alike who see how their properties fall victim to a sea that inches closer every day or to landslides and flash floods that are more frequent.

The $141.4 billion figure in projected costs for Hurricanes Irma and María is only an approximation of the real impact of these phenomena on the economy and social life of the country. In fact, Maria is projected as the third most expensive hurricane in the history of the U.S.

To have an idea of how the cost is magnified with the increased intensity of the phenomena, some $1.7 billion has been disbursed to date for Irma and María, or roughly 63% of the $2.7 billion spent on all the extreme events that occurred in Puerto Rico from 1998 to 2011, including Hurricane Georges.

Even with these figures and seven months after María, a plan to address the effects of climate change has yet to become a priority in Puerto Rico. The September hurricane left more than $90 billion in damages, 183,000 displaced people and the projection of almost 1,000 related deaths. The government tasked George Washington University with a review of the number of deaths related to María. The academic institution expects to release a preliminary report by May.

The effects of María are still visible across Puerto Rico, with areas that still lack power or have intermittent service, many roads without traffic lights and a large number of businesses that have yet to reopen their doors.

According to Díaz, a scientist specialized in marine and coastal resources, the island suffered in less than five years the onslaught of its worst hurricane, María, as well as its worst drought in modern history. Researchers from Cornell University found that the drought experienced from 2014 to 2016 was the worst recorded in the Caribbean in at least 66 years. At its most critical point, more than 2.8 million people were affected by three- and four-day rationing of potable water service. Two years after the event, the Planning Board has yet to finalize the study that would quantify its economic impact.

In contrast, from 2010 to 2013 —before the drought— Puerto Rico recorded monthly and annual rainfall records, many of which ended in floods.

While these extreme events are the most recent, they are far from being the only ones. During the past 30 years, Puerto Rico has faced Hurricanes Irene, Georges, Hortensia and Hugo, as well as another drought in 1994-95, the latter of which totaled $300 million in damages. There were also floods; beach erosion—partly due to the rise in sea levels, but worsened by construction near beaches; deteriorated reefs, including coral bleaching in the 1990s; a decline in fishing; the arrival of sargassum; and the appearance of other signs associated with climate change, such as an increase in the population of mosquitoes, which are vectors of epidemic diseases such as dengue and chikungunya.

There are no economic studies that show an overview of what climate change represents for Puerto Rico. Although it doesn’t provide figures, the Climate Status Report published by the CCCPR in 2013 establishes possible effects for tourism and other industries according to different factors, including floods, changes in temperature and rising sea levels, among others.

Photos and videos in social media taken by scientists and citizens show landslides and the wear of buildings, houses and roads in Rincón, Isabela, Aguadilla, Loíza, Humacao, Barceloneta, as well as erosion in the Palominito islet and in the beaches of Dorado, Vega Baja, Condado and Ocean Park.

Legislative neglect exposed

An analysis by the CPI concluded that from 2005 to 2018, a total of 45 bills and resolutions related to climate change were introduced, but none of them led to an adaptation plan for the island. During the 13-year span, 17 executive orders were also issued, without any significant action achieved either.

During that period, only one bill became law: the Public Policy to Mitigate Global Warming Act (Act 246 of 2008). In addition to creating a Global Warming Board under the Executive branch, the measure mostly focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, rather than mitigation or adaptation strategies geared toward climate change.

The government, however, repealed Act 246 two years later, with the approval of the Energy Diversification Through Renewable & Alternative Energy Public Policy Act (Act 82 of 2010), a bill presented by then governor Luis Fortuño Burset.

The repeal of Act 246 is important for two reasons. First, Act 82 provided that from 2015 to 2019, energy generation from renewable sources should reach 12% of total output. It barely totaled 2% by 2016, or in other words: the government failed to comply with the law’s mandate.

Secondly, even though it was a PNP administration bill, Act 82 garnered the support from all senators and every PNP representative, including Rep. José Aponte Hernández and Sen. Seilhamer. The former co-sponsored Act 246, which was repealed by Act 82. Seilhamer, meanwhile, is the sponsor of Senate Bill 773, which was filed in December 2017 and is currently in public hearings.

Senate Bill 773 —which, if approved, would become the Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change Act— seeks to materialize what Seilhamer and the other senators and representatives repealed eight years ago: make an inventory of and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The goal, according to the bill, is to reduce these emissions by 40% by 2035, from the figures recorded in 1990. In that year, Puerto Rico released 38 million tons only in carbon dioxide.

The bill also copies from the repealed Act 246 the idea to create an entity that would elaborate the Mitigation & Adaptation to Climate Change Plan for Puerto Rico. The proposed entity would be called Experts in Climate Change Committee and the bill would grant it “total autonomy and legal independence.”

Senate Bill 773, likewise, includes the unfulfilled goal of Act 82: to generate 12% of energy via renewable sources by 2019. In addition, it expects that figure to increase to 20% from 2020 to 2027, and reach 33% by 2035.

Put another way —and if Senate Bill 773 is approved by June, as Seilhamer expects— generation of renewable energy on the island would need to increase by 500% in the remainder of 2018 to reach the 12% target.

Meanwhile, the government is focused on the privatization efforts of the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA). Seven months after María, more than 50,000 Puerto Rico residents still lack power while the rest of the population suffer constant blackouts.

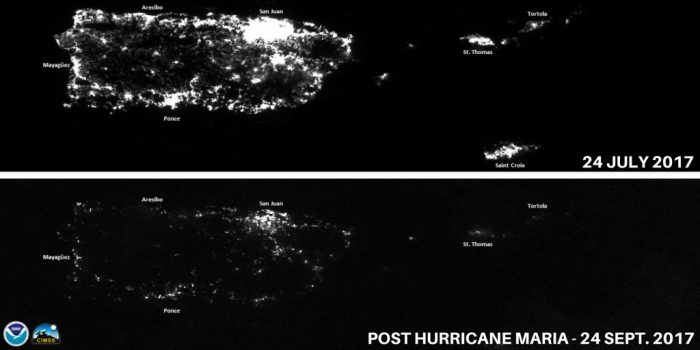

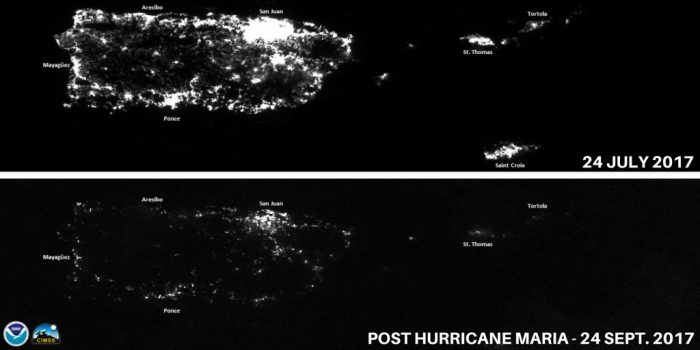

The following map from 2017 shows how much power was lost after Hurricane María in Puerto Rico (Public Domain)

Seilhamer expects the measure to be approved in the Senate by mid-May, so that the House of Representatives has just over a month to discuss the bill and approve it before the current legislative session ends. The senator added that he has spoken privately with the governor, who guaranteed that the $1 million budget allocation provided under the measure will be available, according to Seilhamer.

Although Seilhamer said that Senate President Thomas Rivera Schatz supports the measure and has instructed the PNP delegation to attend to it, he later admitted during the same interview that “even among my fellow lawmakers there is perhaps no concern, or urge, to address this issue.”

Adaptation Excluded From Climate Change Bill

Although Senate Bill 773 has been welcomed as the most recent “first step” of the many that have been taken in the past decade to address the effects of climate change in Puerto Rico, the measure fails to tackle the most important component: adaptation.

An examination of the proposed language and expert testimony during public hearings reveals that the bill doesn’t delve into aspects of adaptation to climate change, such as revision of planning instruments and building codes to construct housing outside vulnerable areas and resistant to extreme events, one of the largest problems that the island faces.

It rather focuses on aspects that were part of previous legislation without much success: a tax credit for installing renewable energy equipment; targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions; and transitioning from fossil fuels to renewables.

It is, in a way, a bet that the threat of climate change could be reduced if the island stops emitting gases into the air, instead of recognizing that rising sea levels, coastal erosion, floods, droughts and the passage of two catastrophic hurricanes are clear signals that climate change is a reality already, driven by the high consumption of fossil fuels worldwide.

Besides failing to promote adaptation strategies to climate change, Senate Bill 773 includes other lapses. The most obvious, for instance, is that it leaves out a DRNA representative and another of the CCCPR from the proposed Experts in Climate Change Committee, probably the two entities with the greatest knowledge on the subject.

The bill also fails to include measures to address coastal erosion and flood problems.

“We must look at the problem of coastal erosion and the implementation of mitigation and adaptation strategies as an alternative to reduce the vulnerability of other manifestations of climate change such as surges, floods and rising sea levels. The beach is a natural barrier, it is the country’s vital natural infrastructure that will allow us to face part of these problems,” said Maritza Barreto Orta, a geologist.

That view, however, is absent in Senate Bill 773. For Barreto Orta, it is unheard of that coastal erosion wasn’t included as a potential risk in the 2016 Natural Hazards Risk in Puerto Rico Mitigation State Plan, commissioned to the firm JM Professional Planning Consultants by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, FEMA and the local State Agency for Emergency & Disaster Management (Aemead by its Spanish acronym).

“To see that coastal erosion has not been included within the priorities that the risk planning instrument that the government of Puerto Rico has used to identify the vulnerability of the territory, its properties, infrastructure and population, is of concern. Even in the section on Climate Change and Global Warming of that Natural Hazards Risk in Puerto Rico Mitigation State Plan, which includes the effects of climate change as a danger for the population of Puerto Rico, the erosion component is not a part of it,” stated in her testimony Barreto Orta, who is also a professor at the Planning Graduate School of the University of Puerto Rico.

When asked by the CPI about this important omission, Seilhamer said the bill would be amended to include coastal erosion among the issues of climate change. As for the lack of adaptation policies, he argued that the proposed expert committee would be tasked with this issue, including aspects such as the relocation of communities in flood zones and the prohibition of construction in coastal areas.

There are also moot or academic provisions in Senate Bill 773 such as those that direct the local Treasury Department to grant a tax credit on the acquisition and installation of renewable energy equipment; the Office of Management and Budget to, in order to approve a construction permit, require that the home has solar water heater; or the Environmental Quality Board (EQB) to quantify and make an inventory of greenhouse gas emissions. There are already laws that oblige these agencies to implement these things.

Lack of Government Interest

The lack of interest in the subject from the government’s side is shown in the absence of information provided by the Executive branch. Rosselló Nevares didn’t answer a CPI request for an interview and none of the government officials provided data on adaptation or resilience plans to address climate change.

Weeks after the requests for interview and information were made, the governor barely included two brief sentences in his State of the Commonwealth address, which was delivered on March 5 and where he indicated that he would support approved legislation to this end. Rosselló Nevares, however, didn’t specify or establish any related measures from his office.

“It is time to work on a holistic vision for the environment and the impact that climate change has on Puerto Rico. I will support the measures that come out of this [Legislature] to address this issue,” the governor stated.

Four days later, in a visit to Loíza —one of the towns where climate change is most evident, in terms of erosion and rising sea level— and following strong swells due to a cold front, he said that “here [in Loíza] we are seeing the effects of global warming. It’s [a matter] that we’re going to work as a government.” The governor added shortly after: “There is a commitment: a short-term commitment to working with the resources we have, but a long-term one that extends beyond Puerto Rico, which is the issue of global warming and the impact that it has in our coastal zone, particularly in this area of Loíza.”

The CPI sought via telephone, email and text messages to contact the Planning Board, EQB, DRNA and Aemead and ask them if the agencies had begun to elaborate a climate change plan for the island following Hurricane Maria. Aniel Bigio, a spokesman for the DRNA and EQB, referred the questions on the matter to Díaz, who confirmed that there is no such plan.

The only three agencies that concluded their plans during the administration of former governor García Padilla were the Tourism Company, the DRNA and the Aqueduct and Sewer Authority.

However, it remains unknown what happened to the implementation of these plans since none of the three agencies answered the CPI.

A Reality Yet to Be Taken Seriously

Scientists in Puerto Rico agree there is a lack of urgency on the issue of climate change among those responsible for developing and executing the country’s public policy.

“While there is a bill already introduced [Senate Bill 773], we are unprepared to face climate change because there is nothing approved. I’m calling and writing to different people linked to those who create public policy to let them know we are unprotected and that we must move to create projects aimed at protecting the coast and communities from climate change and extreme events,” indicated UPR Professor Barreto Orta, who has conducted multiple studies on coastal erosion in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.

“Hurricanes will keep coming and they are going to be bigger and more extreme. We are going to have more extensive droughts. I don’t see that we are doing anything with respect to the things that are really important and for which we have to adapt and prepare. There is legislation for everything in this country. But something that is done here a lot is that they pass legislation to do something, yet they don’t assign a budget. The Interagency Board for the Management of Beaches is an obvious example. And like that, they do a thousand things that are only meant to be heard, for them to say, ‘well look, I proposed this,’” added Ruperto Chaparro, director of the Sea Grant program.

The beach in Humacao, Puerto Rico (Photo by Centro de Periodismo Investigativo)

“Why do you think this happens? We have plenty of scientists, studies that account for the effects of climate change in Puerto Rico and we have experienced extreme events. Could it be that it is a matter of ignorance, of politics, of particular interests that don’t want these issues to be addressed?,” the CPI asked.

“I think it is that politicians don’t understand or relate the impact of change climate with the economy. If you lose the sand in a town like Rincón, you’re killing the tourism industry—hotels, restaurants, condominiums, second homes—which generates property and sales tax revenues for the municipality. It seems that they don’t relate the fiscal health with the health of the natural attraction, which is the base of tourism,” Chaparro noted.

Félix Aponte González, a specialist in climate change adaptation issues in island cities, said that several attempts have been made in Puerto Rico to elaborate a plan or, at least, a strategy to address the challenges presented by the phenomenon in a more concerted manner, “but there has not been enough technical capacity or enough public pressure to move in that direction.”

For Aponte González, Puerto Rico has made great strides in academic research efforts and collaborations between universities and federal agencies to better recognize its vulnerabilities.

He acknowledged, however, that “we have fallen short in presenting a coordinated and adequate response that allows us to execute correctly and ensure that present actions will be able to meet the needs and challenges we see in the future at a climate, social and economic level.”

Aponte González asserted that other parts of the Caribbean have achieved progress on this end, since such groups as the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre (CCCCC) have been able to start joint collaborative work to achieve greater resilience.

In Search of a Plan for Adaptation and Resilience

“To relocate communities and structures at risk, we have to take into account that it took decades, and not six months, to arrive where we are as a country. Even with the urgency of the changes we must make, it has to be gradual and it takes generations. We cannot displace communities and leave them without a place to live,” Aponte González said.

Nevertheless, short-term mitigation measures must be developed for the next 10 to 15 years to take care of those people who are already facing the problems of floods and coastal erosion, he added. Government infrastructure, moreover, in risk areas must be relocated.

Aponte González believes that the government must start by discouraging—and in a best case scenario, prohibit—construction in risk areas such as what is known as the maritime terrestrial zone, areas prone to landslides, flood valleys and remote locations where it is more difficult to build basic infrastructure.

For his part, Díaz pointed at three realities that must be dealt with. First, it must be determined whether existing infrastructure is going to be protected, with cases such as in Rincón where it must be removed from the area, he asserted. The second point to work with is adapting the infrastructure to make it vertically while ensuring it remains functional. Díaz noted that strategies must be developed—from public policies to building codes—to be proactive and that any new investment must not make these new structures vulnerable, but rather be more resilient.

“Legislation has been introduced, evidence has been presented. I believe there is enough receptivity to address these issues, even more in Puerto Rico than in the U.S. nowadays. From a strategic point of view, nobody has to tell us that a hurricane has a devastating force, because we have faced it in the past, but we have just seen the consequences. Our adaptation and reduction of vulnerability to climate change must, at least, consider the forces of this hurricane [María] that we faced,” Díaz said.

This story is part of the series ISLANDS ADRIFT, the result of the work of a dozen Caribbean journalists led by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI) in Puerto Rico. The investigations were possible in part with the support of Ford Foundation, Para la Naturaleza, Miranda Foundation, Ángel Ramos Foundation and Open Society Foundations