By Jeniffer Wiscovitch and Omaya Sosa Pascual | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

Spanish version here.

SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO — Nobody has to prove to Jazmín Cruz-Corporán that the Puerto Rico government did not have a response plan for a massive public health emergency like Hurricane María. She is certain there were serious problems at the hospitals and health facilities before the phenomenon devastated the island.

The woman lived her own nightmare at the Ryder Hospital in Humacao, where her father began the slow and painful path toward death. Gaspar Cruz-Agosto was admitted to the institution on August 30 for diverticulitis. Then, a study showed a mass in the lung, but they could not reach a diagnosis because the hospital was left without electricity after the passage of Hurricane Irma on September 6. Meanwhile, Cruz-Agosto continued to deteriorate.

On September 15, five days before Hurricane María hit, Jazmín arrived one morning to visit her father at the hospital and found him with a disfigured face, making it certain for her that it was clear that he had suffered a stroke. No one in the hospital was able to tell her what was happening and it was not until late in the day that her father was moved to the intensive care unit.

At that time, a doctor told her it appeared her father had cancer, but that it could not be confirmed without a biopsy. They never ran that test.

His health continued to worsen to the point that two weeks after Hurricane María, they had to amputate a leg due to bad circulation. The misinformation continued and nobody was allowed to see him. The only thing Jazmín knew was that the hospital’s power generator stopped working after the surgery.

Gaspar Cruz Agosto (photo courtesy of family)

The outlook in the hospital was terrifying. The Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI for its Spanish initials) has documented dozens of similar testimonies from this and other hospitals and health facilities after the hurricane.

At the Ryder’s emergency area, there were stretchers in all corridors. Patients in the intensive care unit had been moved to the emergency room area because the intensive care infrastructure had been affected by the hurricane. New patients arrived at the emergency room and were not attended to because intensive care patients were there, she said.

“All of the sudden, it was as if I was in a movie, we started hearing helicopters and ambulances coming. We went outside the hospital to see what the chaos was, and there were helicopters carrying some patients to take them to the [hospital] ship. They were taking patients quickly in ambulances to the Caguas hospital and HIMA in Humacao,” she recalled.

Outside the hospital, an acquaintance of Jazmín warned her not to leave the place, since there was the possibility that they would move her father to another health facility. And it happened: they put the 73-year-old man, a resident of Las Piedras, in an ambulance to move him to another hospital, just an hour after having operated on him. His daughter did not even know where they were taking him because they never told her. She got into her vehicle and drove behind the ambulance to find out where they were taking her father.

She arrived at the HIMA hospital in Humacao and there, the situation was equally as terrible. The doctors did not even have her father’s file. The next day, Ryder sent part of the medical information in photos.

“Everything became complicated, he never received the treatment, the therapies. Everything he needed, was not done,” Jazmín lamented.

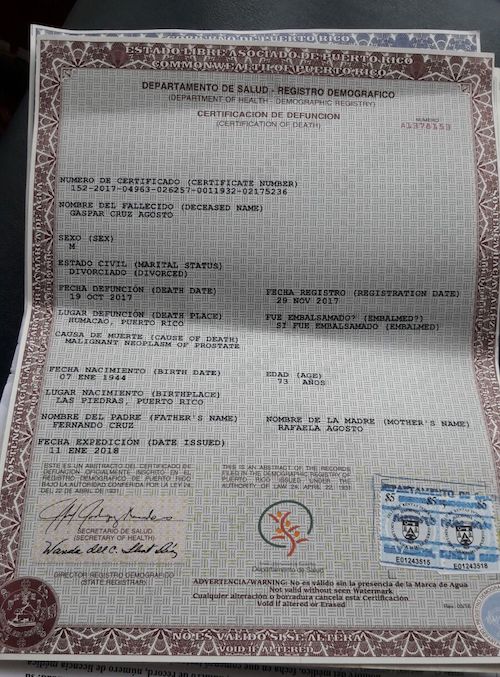

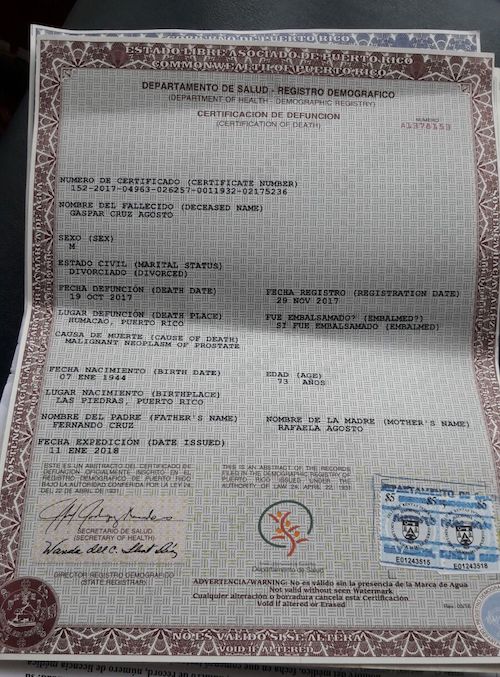

He only received pain medication and an IV. On October 19, Gaspar died at the HIMA in Humacao. His cause of death, according to the death certificate, was malignant neoplasm of the prostate (cancer). His daughter says that her father was never diagnosed with this illness.

At the close of this edition, Ryder’s executive director, José Feliciano, who was asked to react, did not return calls.

An Old, Systemic Problem, Which Worsened With the Hurricane

At least a decade ago, the government of Puerto Rico had abandoned its responsibility to ensure the proper functioning of health facilities on the island and to have a response plan for medical services in case of a catastrophe, an investigation conducted by the CPI during the past six months found.

Documents and interviews revealed that at least since 2009 the Department of Health (DS) does not regularly inspect a good part of these 400 institutions, which include hospitals, diagnostic and treatment centers, and homes. The investigation even detected a case, of the Diagnostic and Treatment Center (CDT, by its initials in Spanish) in Manatí, which had not been evaluated in more than eight years.

The exact number and names of all the facilities that had not been inspected prior to the hurricane for more than two years as dictated by the regulation could not be specified because the Health Department refused to give the information to the CPI. However, the agency acknowledged that it does not have the capacity to inspect about 40% of the 68 hospitals it has licensed. Two sources familiar with the system, who spoke on condition of anonymity, indicated that the Health Department concentrates the few inspectors that it has in hospitals, so the neglect of the other facilities is even greater.

The Health Department is the agency legally required to license hospitals and health facilities in Puerto Rico. Hospitals can also be evaluated by the Joint Commission of Hospitals in the United States, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting the quality of services that is financed by the fees paid by the evaluated hospitals. This accreditation is voluntary, the organization does not normally withdraw accreditations because its philosophy is to work with hospitals to improve them, and declined to provide a copy of their inspection reports.

$36 Million Later, Where’s the Plan?

The CPI’s investigation also revealed that the Health Department lacked, and still doesn’t have, a comprehensive response plan for emergencies or massive catastrophes in Puerto Rico to guarantee the responsible management of patients and minimize deaths.

This document is what the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services calls the Health Care Preparedness and Response Capabilities and which the agency recommends developing in states and territories. The plan contains what the entire jurisdiction’s health system —including its public and private facilities— has to do to prepare itself to respond effectively to emergencies that affect public health

The executive president of the Puerto Rico Hospitals Association, Jaime Plá, said in an interview with the CPI that he has never seen a document of this nature.

creJaime Plá (Photo by Leandro Fabrizi Ríos | Center for Investigative Journalism)”No, there was no plan. In many areas, there were basic response plans,” he said when asked if the government had given hospitals any type of document with guidelines on how to respond to an emergency prior to Hurricane María.

He said each hospital has an internal emergency response plan and they delivered a copy of it to the Health Department.

After the disaster, the government has organized meetings in which the Association has participated as well as the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and other agencies, to discuss how to address the area of health response in an upcoming natural disaster as a result of the Maria experience. Plá said he believes the government should be presenting a plan in the coming weeks, but that he has not yet seen a document, one week before the start of the new hurricane season. “If there is something written for that, I don’t know it. I haven’t seen it,” he said.

He pointed out that where hospitals need help from the government it is in the coordination of services, and guides on what happens if they have to close a facility, where those patients be sent and how.

“If it [a plan] exists, it would be good if they sent it to us to review it and make sure it is functional. The problem is that the plans are functional, that they aren’t desk plans… What the governor things is not important, it’s important what he tells all of us to be able to act,” he said.

What does exist, according to two sources consulted, is a response plan that covers only the government’s health facilities which, after the privatization in the 1990s, are scarce and only include secondary and tertiary hospitals in the Metropolitan Area.

Health Secretary Rafael Rodríguez-Mercado refused to answer the question of whether any type of response plan existed or exists, nor did he provide a copy of the document requested by the CPI. His spokesman, Peter Quiñones, replied in his place saying that they are “working on a possible press conference on this subject,” after weeks of insistence by the CPI.

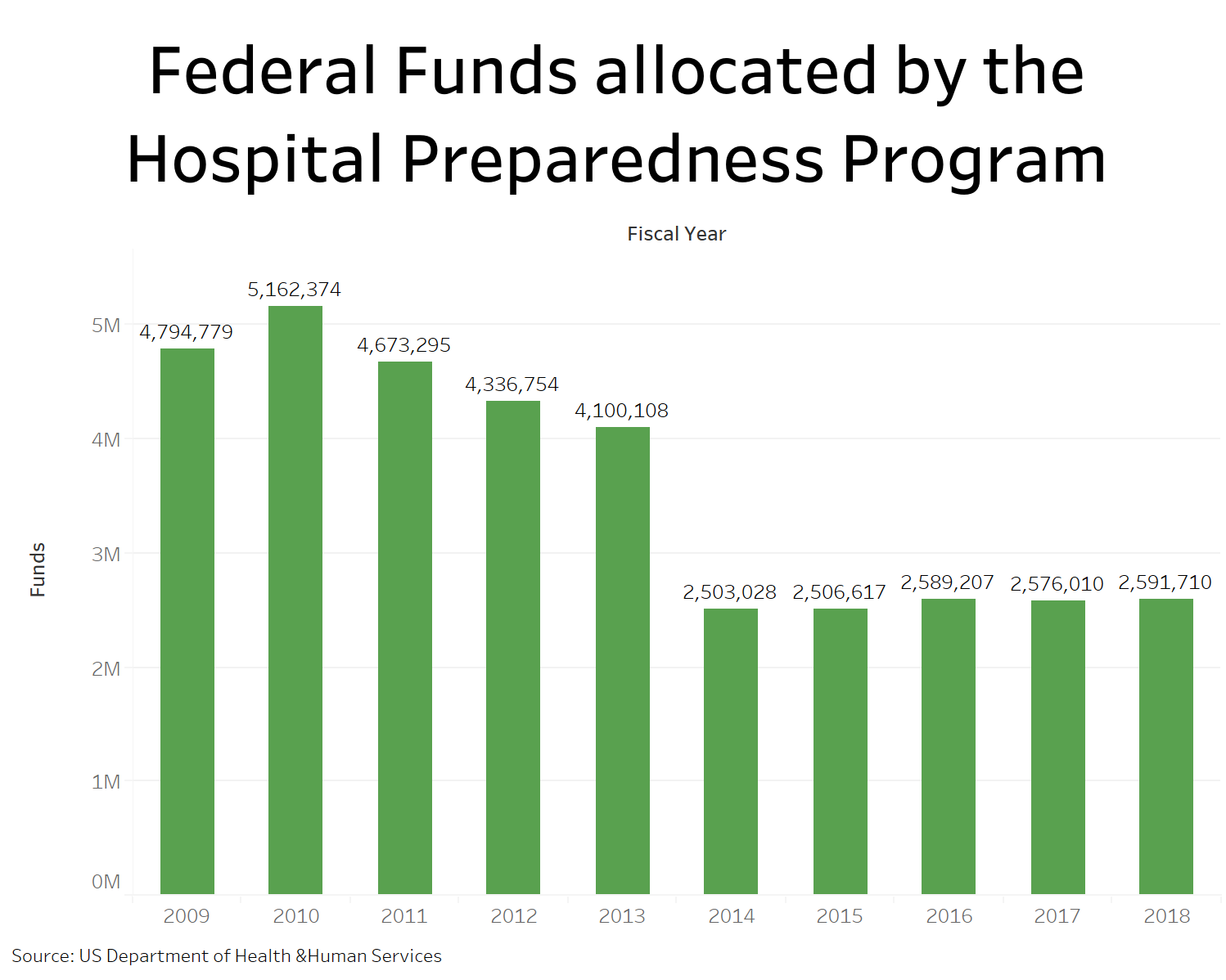

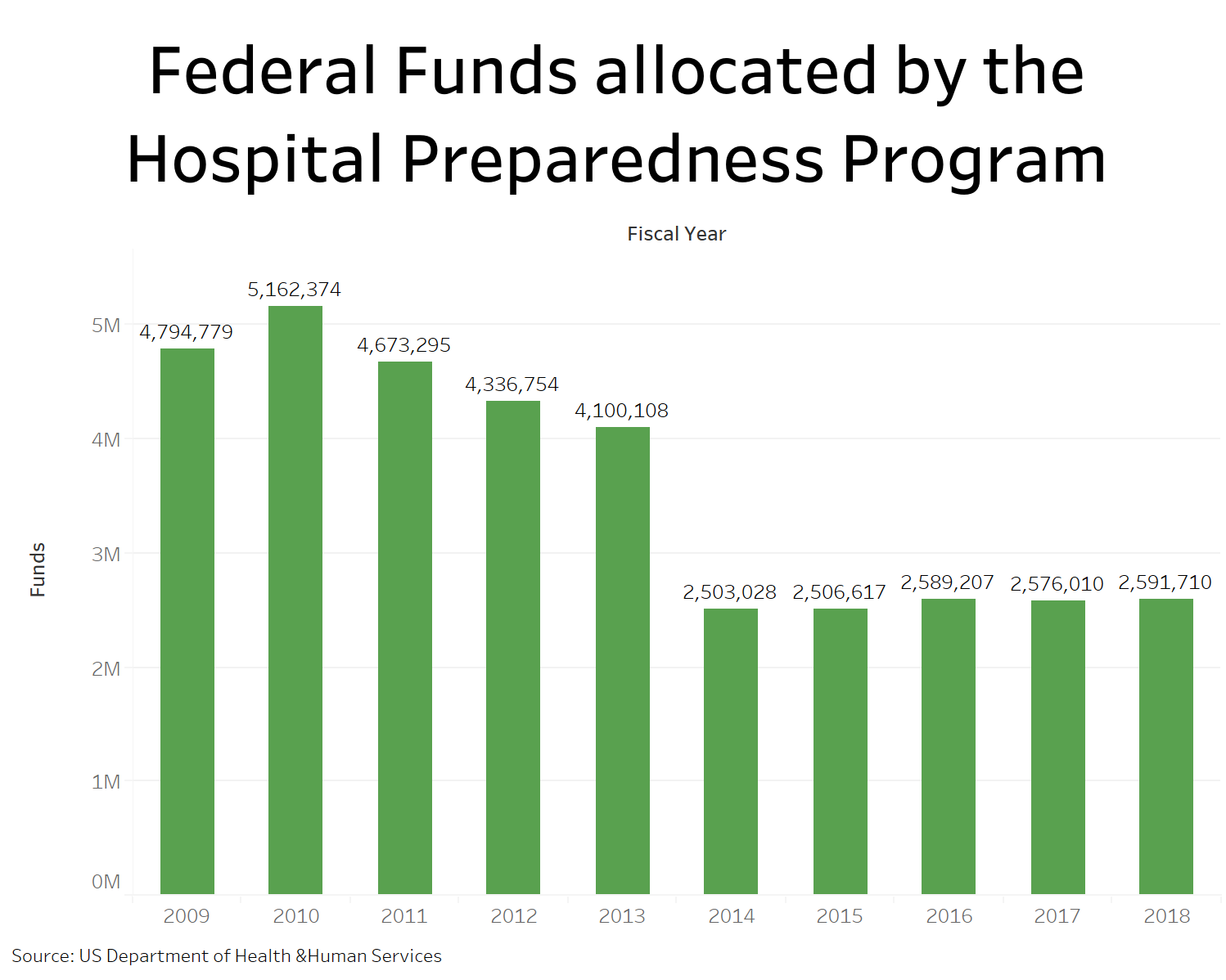

A comprehensive and realistic plan was supposed to be drafted from regional plans that were the responsibility of the Health Services Coalitions that the agency established with federal funds six years ago. This initiative is part of the federal Hospital Preparedness Program that has granted more than $36 million to the Puerto Rico Health Department from 2009 to the present year.

But the plans weren’t developed, Liza Millán, planner for the Health Services Coalitions, admitted to the CPI.

Millán said each hospital should have its operational plans to deal with emergencies, but that through the Coalitions, it is intended that all health institutions and facilities in each area be governed by the same plan.

“If there is an emergency in the region, it is assumed that a regional plan is used,” she said in January during the first meeting of the Aguadilla-Mayagüez region Coalition. Now, after the storm, they are developing these plans, she added.

The Health Department’s Office of Public Health Response Preparedness and Coordination Office, whose mission is to prepare the Health Department’s seven regions, as well as any facility that provides health services, for a public health emergency. These Coalitions have been meeting for six years, however, it was not until the beginning of this year 2018 —four months after Hurricane María— that they began to work with their strategic plans and preparedness.

“[The goal is] to develop a regional plan because there was none, and they had to communicate informally [during Hurricane María.] When I say informal is that there was nothing written, there were no assigned responsibilities,” Millán explained.

60% Died in Health Facilities

A sample of cases of Hurricane María’s fatal victims documented and analyzed preliminarily by the CPI and Quartz, a specialized media in data journalism, points out that more than 60% of the deaths linked to the disaster occurred in hospitals, CDTs and homes in the island.

Those cases, reported directly by relatives and acquaintances through a form developed by both media outlets and public health experts, showed that the majority of those deaths took place in the weeks after the hurricane, not the day of the event, and according to family and friends of the deceased in the testimonies provided in the forms and subsequent follow-up interviews, they occurred in circumstances related to problems with basic services at these facilities or other health services operations such as drug stores, medical offices, specialized treatment centers for dialysis and chemotherapy, that were not offering vital services or that had to close their doors, leaving patients adrift.

Among the problems reported are faults in medical equipment or an inability to use them due to lack of electricity, unhealthy conditions due to humidity and heat, lack of supplies such as oxygen and medicines, and lack of facilities to refrigerate medications. These situations continued to occur weeks and months after María’s passing, according to the sample.

Millán, as well as Ada Santiago, specialist of the Health Department’s Coalitions, agreed that the big problem in hospitals and other health facilities during the emergency, in addition to the lack of drinking water and electricity, was the oxygen supply.

“Every hospital had oxygen problems,” said Santiago.

“The problem with oxygen, which perhaps people don’t understand, is that its private companies [that supply it.] The hospitals’ job is not giving you oxygen, it is attending emergencies. A person in need of oxygen, in a declared emergency, is not a priority for a hospital, so they were not receiving them. That is standard; In an emergency, hospitals will limit their services, because they are limited in terms of personnel and resources. They will focus only on emergency situations,” said Millán.

There are a number of lung and respiratory conditions that require people to use oxygen as a support mechanism to live in their homes or in nursing homes. These cases do not constitute a medical emergency, but if they stop receiving oxygen they can worsen and become an emergency or death. Regularly these patients receive oxygen supplies in their place of residence, but after the disaster, the companies stopped making the deliveries and the patients went to the hospitals in search of their vital dose. But hospitals are not designed to provide these types of support services and do not have reserves for it. The amount of oxygen that they acquire and store is for their emergency services and surgeries, which is much smaller.

Government Says There Are No Resources to Inspect

The actual state of all the institutions prior to the natural disaster and whether they met the contingency standards in the face of this type of emergency, as well as the magnitude of the government’s neglect in overseeing them, cannot be determined because the government refuses to turn over the names of the facilities inspected, dates of visits and reports with results to the CPI, claiming that it is confidential information.

This, despite the high level of public interest and the significant increase in deaths at these institutions six weeks after the hurricane, when the average rate of deaths in hospitals soared by 38% compared to 2016 and in homes by 77%, according to Health Department statistics.

The Deputy Agency for the Regulation and Accreditation of Health Facilities (SARAFS, by its initials in Spanish,) the Health Department’s division in charge of the task of inspection, has not counted on the resources for the task at least for the past 10 years.

In 2009, Deputy Secretary Rosa Hernández testified during an investigation by the Puerto Rico Senate that because of the dismissals under the Fiscal Emergency Act of 2009 (Law 7,) it was left with only four inspectors, which had prevented them from validating if all of the island’s hospitals and stabilizing rooms complied with the law’s requirements.

The official who currently holds the position, Verónica Núñez, acknowledged in an interview with the CPI that she has not been able to inspect all the institutions every two years, as required, because although she now has 10 inspectors, they are not enough.

“There are too many facilities for inspectors and clearly it can’t be done, it has to be programmed in such a way to cover as many different facilities as possible. That’s why they are not inspected in full,” she explained.

“We do what we can,” she said.

It was not until September 27, a week after the cyclone that the SARAFS inspectors took to the streets to inspect the hospitals to see if they were meeting the minimum requirements to be able to provide health services, Núñez said.

On October 18, a month after the hurricane and following an investigation published by the CPI on the chaos that prevailed in hospitals proclaimed by the government as the regional centers best prepared to care for patients, was when Health Secretary Rafael Rodríguez-Mercado issued Administrative Order 374 for SARAFS inspectors to inspect the hospitals every 72 hours.

Rafael Rodríguez Mercado (Photo by Metro PR)

They found that hospitals “were not 100% compliant” with Puerto Rico’s Health Facility Law 101 and Regulation 117 that governs the licensing, operation and maintenance of hospitals in Puerto Rico, the official said, but declined to offer details about breaches, alleging this information is confidential.

The official said from the end of September to December her inspectors carried out 359 inspections, but did not allow the CPI to obtain a copy of the results of the inspections, nor details about the findings. There were no fines.

She said SARAFS only recommended the closure of one hospital, the Buen Samaritano in Aguadilla, which was closed from October 7 to November 17, 2017, one day after the CPI denounced the conditions in which it and two other hospitals that were operational, according to the government. The recommendation arose because said hospital had patients intubated in the Intensive Care Unit and dependent on ventilators, without electric power and operating with a single generator. The facility did not have a backup generator.

The other two closures, according to SARAFS, were the Health South Rehabilitation Hospital in Manatí y and the Susana Centeno Family Health Center in Vieques. The Manatí hospital was temporarily and voluntarily closed from September 27 to November 16, 2017, due to damaged sustained from the hurricane. In the case of the hospital in Vieques, it was closed upon an evaluation and recommendation from the Health Department, federal Health and Human Services (HHS) and the U.S. Corps of Engineers. It remains closed.

Núñez did not mention the closure of two other hospitals after the hurricane, as confirmed by the CPI: the Susoni Hospital in Arecibo and the Ryder Hospital in Humacao. Eight months after the hurricane, Ryder only keeps its emergency room open, while its operating rooms, deliveries and some floors are still closed, the institution confirmed.

The omission adds to the government’s inconsistencies in the closure of hospitals and health facilities just after the cyclone. On September 26, Health Secretary Dr. Rafael Rodríguez-Mercado told the CPI that 70% of the hospitals were closed and only 18 remained open.

Rodríguez never again gave an interview to the CPI on the subject. A week later, Puerto Rico Governor Ricardo Rosselló announced at a press conference that 63 of the island’s 68 hospitals were already “operational,” and the following week he said all hospitals were open, without explaining how he managed to reopen the 56 hospitals that were closed two weeks before. Hours after this last announcement, La Fortaleza had to announce that Ryder in Humacao was closing.

The same week that the governor announced that all hospitals were open and “operational,” the CPI found that Susoni was closed, and others were not able to care for patients or had closed areas such as Pavia in Arecibo and the Buen Samaritano in Aguadilla.

La Fortaleza assigned Public Affairs Secretary, Ramón Rosario, instead of the Health Secretary, to answer the CPI’s questions on the subject and explain the inconsistencies. Rosario said the designation of “operational” only meant that “they were receiving patients.” He also said there was no reason to offer additional information to citizens about the real conditions in hospitals because the island’s health system was functioning “as usual.” One day after the CPI’s publication, the government closed the Buen Samaritano.

Finally, Núñez said she did not know whether the regulation for licensing hospitals and health facilities in Puerto Rico, which her unit manages, contains some provision that requires institutions to have an emergency response plan.

“I believe there is a chapter on emergencies, but if it is, I believe it is very vague, I have to corroborate it again, because I don’t think it has one,” she said.

The CPI corroborated that this chapter effectively does not exist. The only thing that exists is a reference to hospitals having to stock-up water supplies ready in case of emergency.

CDT’s and Hospitals Under Investigation Before María

The conditions in which the hospitals were in before María had already motivated the start of several legislative investigations.

Among these, an investigation launched in 2017 by the Puerto Rico House of Representatives’ Health Commission to probe the services offered by government-owned hospitals and CDTs. The measure, House Resolution 57, was presented by Rep. Juan Oscar Morales.

The Commission initiated visits to the CDTs and hospitals, finding, among many deficiencies, deteriorated physical plants not suitable for patients or employees. In addition, they found reports indicating problems issued by SARAFS that took more than two years to address. There were no fines.

According to Rep. Morales, SARAFS issued a report with a few notes to the Guayanilla CDT in September 2016 and it was not until January 2018 that the hospital administrator submitted the corrective plan to SARAFS.

The representative said he did not know what the findings were in detail, because on the day of the visit, the SARAFS representative who was present did not have it on him.

In the case of Manatí, the lawmaker said the Commission found that SARAFS had not visited the CDT of said municipality for eight years, since 2008, when according to regulations, the visits have to take place at least once during the two years that their licenses are valid.

Another hospital visited was the Río Piedras Medical Center. It was a surprise visit to validate complaints that patients spend weeks in the corridors without being seen by doctors.

“We went and found there were people who had not been seen for days,” said the lawmaker, who also mentioned that during his visit they found people waiting outside, instead of in the waiting room, since there was no space.

In Vieques, the situation found in July of 2017 was gloomy: a CDT with areas without air conditioning, broken mattresses to such an extent that the patients reported feeling the cold from the pipes underneath the beds.

The air conditioning issue will be the subject of an additional investigation, since during the last administration air conditioners were bought at a cost of $400,000, which worked only four or five months, approximately. Then, they acquired mobile units for which they paid about $8,000 a month, instead of repairing the expensive air conditioning units that had been bought. Today, the CDT is closed.

The Commission returned to the Medical Center after Hurricane María, on Nov. 7, 2017, after rumors that it was inoperative. They found it was working, but with power generators and receiving an excessive number of patients. “I was too full,” he said.

Another visit made after María was to the Ramón Ruiz-Arnau University Hospital (former Regional Hospital) in Bayamón. Although it suffered severe damage to the roof and did not have adequate conditions to house patients and employees, it never stopped operating. On the contrary, it became a regional hospital that received people from Naranjito, Barranquitas and Orocovis, addressing the patient pile-up at the Medical Center.

An investigation into the services offered by hospitals was also launched in the Senate in March this year. The Health Commission will have to submit a detailed report on their findings in 90 days, according to a statement sent by Sen. Ángel “Chayanne” Martínez, author of Senate Resolution 520, filed in November 2017, but approved in March of this year.

According to the legislator, initially, U.S. Department of Health staff, coupled with members of the U.S. Army Reserves, were in charge of carrying out inspections to evaluate the operation of the hospital facilities. That inspection showed that during the first weeks, most of the hospitals provided only Emergency Room services, while the Operating Room was available in others.

“In the past few months, many of the public and private hospital facilities suffered damage. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the current conditions in which hospital centers operate. Similarly, it is very important to know the recovery plans for the affected areas and the restoration of interrupted services,” the chairman of the Senate Ethics Commission said in March. This has not happened and the hurricane season begins again on June 1.

In 2016, Sen. Rosanna López-León, then-chair of the Commission on Civil Rights, Citizen Participation and Social Economy, also investigated the services offered by hospitals and mental health institutions. López-León sent letters to all the hospitals seeking to learn what was really happening after the hurricane. However, only the HIMA San Pablo hospital in Caguas responded to the letter.