By Damaris Suárez

Versión en español aquí. Originally published by the CPI here in Spanish on June 5.

The government of Puerto Rico lied and it knows it lied.

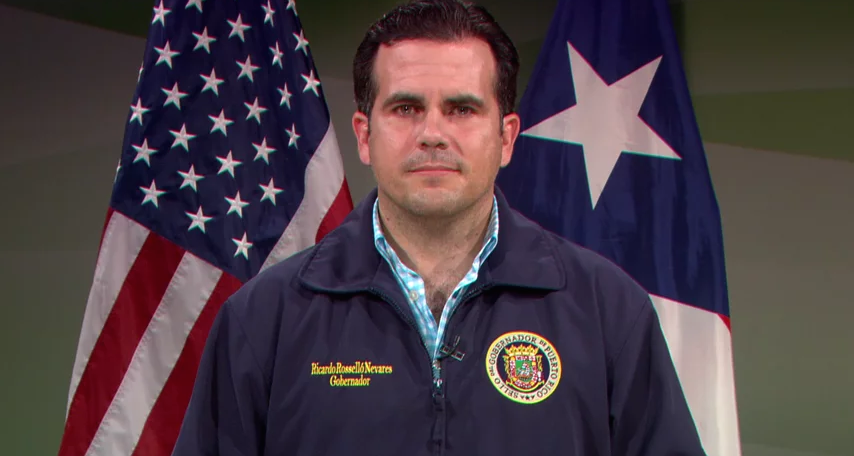

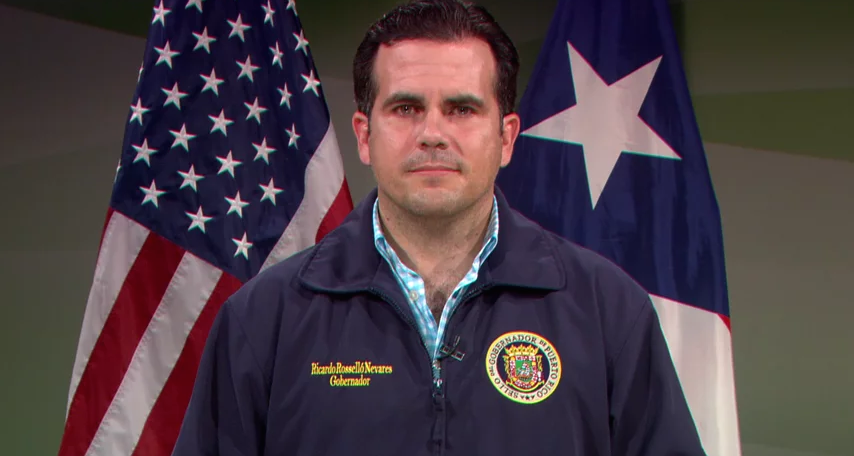

The irregular handling of the death toll data after the passage of Hurricane María continues to hound the Ricardo Rosselló administration. The magnitude of the problem has snowballed in the international public eye, the result of a lack of deliberate transparency that, in the case of those who died, began just days after the hurricane hit last September.

It took months of news coverage, three lawsuits, analysis by multiple experts, a Harvard University study and Rosselló being challenged on CNN about the lack of access to mortality data after the hurricane for the island’s Demographic Registry to publicly share charts of total deaths in 2017 until May 2018. This information still falls short of the claim (and subsequent lawsuit) made last year by Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI) to access all the mortality data held by the government that occurred in Puerto Rico and their causes. (Editor’s Note: Hours after this column was published on Tuesday, judge Lauracelis Roques Arroyo ordered that the government turn over all this hurricane-related mortality death to the CPI.)

Because a lot is still missing: Where did people die? How did they die? Where were people from? How old were they? What was the cause of each certified death? All these questions will help us understand what happened and how to prepare for the future. And, among other documents, death certificates are still missing. This is crucial information because with these certificates, you can compare it with the information provided by the government and inquire into more details about how people died.

Governor Rosselló and the director of the Demographic Registry, Wanda Llovet Díaz, are not telling the truth when they say that the data has always been available. As recently as May 21, the Demographic Registry’s attorney, Cristina M. Abella Díaz, explained in court that although initially a list of the names of the deceased and the municipalities was made public, subsequently, the registrar exercised her discretion to determine that the data would not be made public until the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) validated it in November 2018. More than a year after the tragedy!

The lawyer’s statement was made at a court hearing for the lawsuit filed by the CPI in February after months of failed attempts to get detailed mortality statistics from the Demographic Registry with detailed information after the hurricane. CNN joined the efforts, filing its own lawsuit, which was consolidated with the CPI’s lawsuit. (Editor’s Note: The lawsuit was resolved on Tuesday, in favor of the CPI and CNN.)

“That is preliminary information. The CDC is who tabulates and validates all this. Until that is done, those numbers are not final or conclusive… It will be available in November,” Abella Díaz said at the time, referring to the database on the causes of deaths in Puerto Rico after María.

The issue of deaths related to the passage of Hurricane María was revived last week, after the Harvard School of Public Health published a study using surveys organized with academics from the island’s Carlos Albizu University. The study estimated that 4,645 people may have died in excess between September 20 and December 31. The official government figure is 64.

The government also denied official data to Harvard researchers, the study’s researchers said. The same week in which the Harvard findings were made public, Puerto Rico’s Institute of Statistics went to court to demand that the Demographic Registry share the mortality data.

It is absurd that the government keeps insisting that the data has always been available if they have refused to deliver it since October of last year. For a government that boasts so much in promoting transparency, the secret management of such data reveals a very different pattern in how public information is managed.

Almost nine months after the storm, the government of Puerto Rico and federal authorities are in the eye of another storm, caused by the disparity of the official death numbers ever since the Harvard study was published.

The publication has revived the debate in the United States about the poor immediate response of the federal government after the hurricane and the need to establish a congressional commission to conduct an investigation.

What is so evident for many right now, began a few days after the hurricane passed through the island. On September 28, the CPI revealed that the death count after María was being underreported (the first of more than a dozen articles showing that the government was not reporting the actual number of deaths after the hurricane) and that bodies were accumulating in the morgues of Puerto Rico’s 69 hospitals.

In that first article, Health Secretary Rafael Rodríguez candidly acknowledged that the morgues were full and that the deaths related to the hurricane were many more than those officially documented. He even said he knew of cases in which people had chosen to bury their relatives in mass graves because they were in places where there was no access.

This was the first and last interview the Secretary of Health gave about the deaths. He simply disappeared, or better stated, he was asked to disappear. From that moment, Rodriguez said that the official authorized to issue statements on this issue would be Public Security Secretary Héctor Pesquera.

Although the CPI team (headed by journalist Omaya Sosa Pascual on this beat) kept following the unusual official number of deaths that contrasted with the versions of victims’ relatives, Pesquera and government officials chose to minimize the matter, calling the the team a bunch of conspiracy theorists, among other insults.

After more than a month in which the CPI requested the detailed information of deaths from the Demographic Registry, the government published a total figure of deaths for only the first 10 days after the hurricane, raising the hurricane-related count to 55 in a November press conference headed by Pesquera.

After receiving a letter from Legal Aid Clinic lawyers from Interamerican University’s Faculty of Law on behalf of the CPI, the government finally delivered the list with the names of the lives lost, according to the official number of 55 deaths certified by cause of the hurricane, except for the names of seven people whose bodies had not been identified by their relatives.

The disclosure of this information came in November and preliminarily confirmed the versions of victims’ relatives interviewed by the CPI that the deaths occurred due to problems with essential health services and other circumstances caused by the lack of power in homes and hospitals throughout the island.

The latest official data shared by the Demographic Registry dated back to December 2017 (an updated version was sent to Latino USA on January 4, 2018). After this date, the agency ignored the CPI’s multiple requests.

Ironically, the governor was surprised last week when he discovered that his administration had refused to offer information related to the deaths that occurred in Puerto Rico after María. So, no one had informed the governor that his government was sued for denying access to this information?

And did anyone inform the chief executive that only a few days ago there was a court hearing in which the lawyers representing his government defended the decision not to publish the data of the deaths after the hurricane?

It was no coincidence that the day after the CNN interview with the governor, the Demographic Registry published a partial release of the information that until that moment it had refused to deliver, in a clear attempt at “crisis management,” as they call it in public relations.

Would they have acted the same way if the question, instead on CNN, had been in Spanish at a local station? Another example of Colonized Syndrome 101.

The government’s refusal to deliver vital data is just one instance of many in which the government acts contrary to the vaunted transparency it claims to defend. Every day, local journalists face obstacles and excuses to obtain public information from agencies and corporations.

It seems that the government decided to suddenly appear transparent, motivated more by the claim of some than of others.

* The author is a journalist for the Center for Investigative Journalism and president of Puerto Rico’s Association of Journalists.