By Douglas Massey, Princeton University

The news today is full of dire pronouncements about the “crisis” at the Mexico-U.S. border. In reality, there is no crisis, at least as portrayed in the press and by the Trump administration.

Undocumented entries across the border are, in fact, at all-time lows. The mass entry of migrants from Mexico seeking work is over and done with.

The people now arriving at the border are not Mexican workers, but a much smaller number of families from Central America seeking to escape dire circumstances caused in part by U.S. military intervention in the region during the 1980s.

Given President Trump’s demand for the construction of a border wall, many people may no doubt be surprised to learn that net undocumented migration to the U.S. has been zero or negative for a decade.

Falling Immigration From Mexico

All data indicate that undocumented migration from Mexico, in particular, has ended and at this point more unauthorized Mexicans are leaving the country than entering it. According to estimates from the Pew Hispanic Center, the Center for Migration Studies and the Department of Homeland Security, the undocumented Mexican population stopped growing in 2008 and has been trending downward ever since.

Independent data from the Mexican Migration Project, of which I am co-founder and co-director, likewise show that the rate of undocumented migration from Mexico is approaching zero.

Undocumented migration from Mexico actually began to decline around 2000 and took a nosedive when the Great Recession hit in 2008, from which it never recovered.

Mexican migration ended not because of U.S. border enforcement, but because of Mexico’s fertility transition. The number of children per woman declined by about 68 percent between 1960 and 2016.

As a result, Mexico has become an aging society. The population’s average age has risen from 16.6 in 1970 to 28.6 today.

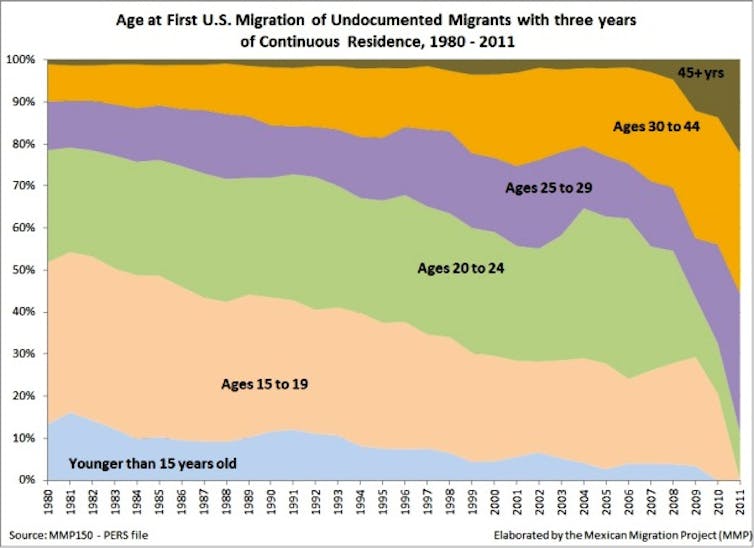

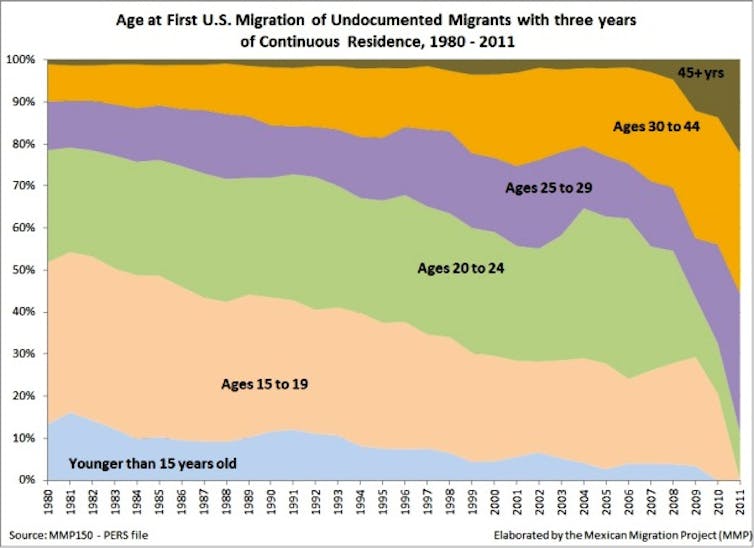

Like other demographic processes, such as fertility and mortality, migration is highly age dependent. The likelihood that someone will migrate out of a country rises rapidly through the teenage years, peaks in the early 20s and then declines rapidly to low levels by age 30. With the average age in Mexico rising and the number of people aged 15 to 30 falling, the likelihood of Mexicans migrating to the U.S. without authorization moved rapidly toward zero.

Today, Mexicans are apprehended at the border at record low levels, leaving Central Americans as the group principally seeking to enter.

Migration From Central America

Unlike migrants from Mexico, most Central Americans are not labor migrants. They arrive as families or minors traveling without their parents. According to data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, among family units apprehended at the southwest border in 2017, 80 percent were from El Salvador, Guatemala or Honduras. Among unaccompanied children, 95 percent were from these nations.

Administration officials and the press have made much of recent increases in the monthly number of border apprehensions and the apparent growth in border arrests since last year. Fluctuations from month to month are normal. Slight increases between 2017 and 2018 obscure the fact that the trend in border apprehensions has been steadily downward.

In 2000, 1.6 million migrants were apprehended along the border, but by 2017 the number was only 304,000.

This quantity may seem like a lot, but it is the lowest number of apprehensions since 1970, when the Border Patrol only had around 1,600 officers. Today, there are more than 19,000 officers. In fact, the number of apprehensions per officer is at its lowest level since 1943.

Although apprehensions so far in 2018 are running ahead of 2017, the difference is slight. Through May this year, there were 252,000 apprehensions, compared to 225,000 through May of last year.

Escaping Civil Warfare

Before 1980, the flow of Central American migrants to the U.S. was small. Legal migration from the region totaled 135,000 during the 1970s, but it ballooned between 1980 and 2010.

Around 80 percent of those entering since 1980 were from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, places from which the Reagan administration launched its Contra War against Nicaragua’s socialist Sandinista regime. Nicaraguans were welcomed as refugees, but emigres from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras politically could not be admitted as refugees or asylees with legal status, since they were fleeing countries with right-wing regimes allied with the U.S.

As a result, the number of undocumented migrants from these nations increased from the tens of thousands in 1980 to an estimated 1.5 million in 2015.

During the 1980s, migrants left these nations to escape civil warfare unleashed by the U.S. intervention. They kept migrating through the 1990s because the wars had destroyed their economies and introduced endemic gang violence into the region. In 1979, GDP per capita in those nations was 80 percent that of Costa Rica and Panama. Today, the ratio stands at just 46 percent.

Gang violence also stemmed directly from the U.S. intervention. The infamous MS-13 gang first formed in Los Angeles among young Salvadorans who were adrift and jobless without legal status. The homicide rate in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras is near 70 people per 100,000 today.

In terms of numbers, there is no “crisis” at the border. Undocumented migration from Mexico is over, and irregular movements from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras are small by historical standards.

If there is a crisis, it is in my view a human rights crisis. Families and children seeking asylum from horrendous conditions in countries of origin are being unlawfully turned away at the border or being arrested as criminals instead of having their asylum claims adjudicated.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.