By John D. Sutter and Omaya Sosa Pascual

Spanish version here.

Ramón Díaz García’s room in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico, is hauntingly empty following his death, which is labeled in records as related to the bacterial illness leptospirosis. (Photo by John D. Sutter | CNN)

Puerto Rico’s own records list so many cases of the bacterial disease leptospirosis that officials should have declared an “epidemic” or an “outbreak” after Hurricane María instead of denying that one occurred, according to seven medical experts who reviewed previously unreleased data for CNN and the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (CPI).

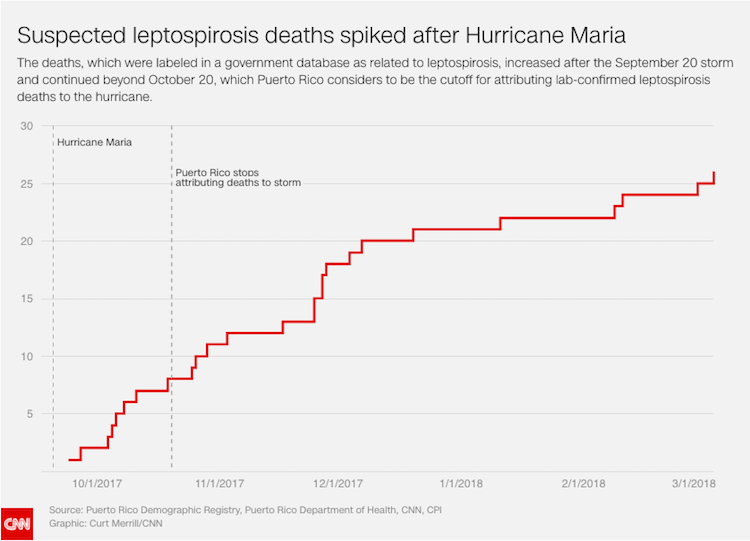

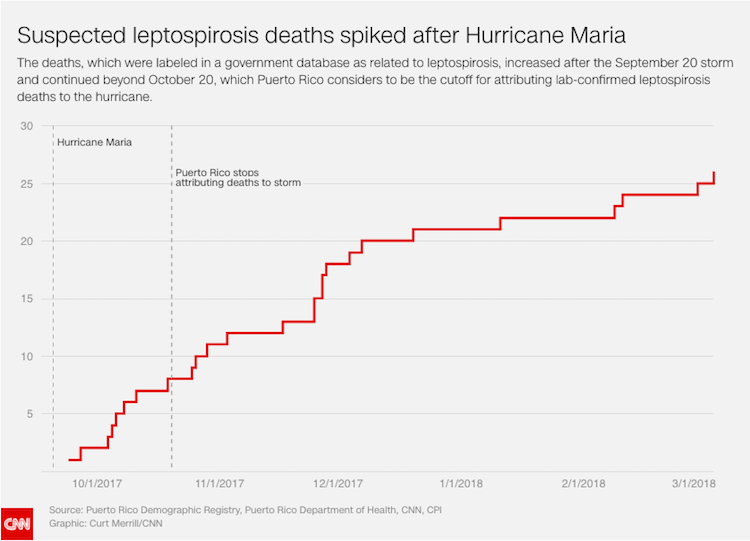

A Puerto Rico mortality database —which CNN and CPI sued the island’s Demographic Registry to obtain— lists 26 deaths in the six months after Hurricane María that were labeled by clinicians as “caused” by leptospirosis, a bacterial illness known to spread through water and soil, especially in the aftermath of storms. That’s more than twice the number of deaths as were listed in Puerto Rico the previous year, according to an analysis of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) records.

“Twenty-six deaths attributed to leptospirosis—that’s extraordinary,” said Dr. Joseph Vinetz, a professor of medicine at the University of California San Diego and an expert on the disease, who reviewed the data. “There’s no other way of putting it… The numbers are huge.”

Puerto Rico’s Health Department attributed only four leptospirosis deaths to Hurricane María until June 22—when it added two more after CNN and CPI asked about the 26 deaths. Officials maintained that the timing was related to laboratory tests and not questions from reporters.

Laboratory tests typically take weeks, not months, experts said.

The two additional deaths have not been added to the official Hurricane María death toll of 64. A spokeswoman for the Department of Public Safety, which determines the death toll for the storm, said the government will not adjust the number until the researchers it hired at George Washington University complete a review of the death toll from the hurricane.

The Hurricane María death toll has come under intense scrutiny following investigations by CNN, CPI and others. In May, a study in the New England Journal of Medicine estimated, based on interviews, that 793 to 8,498 people died related to Hurricane Maria, with many of those deaths being attributed to the lack of services, like electricity, in the storm’s aftermath.

The mortality database does not indicate whether the cases were confirmed in laboratory tests as related to leptospirosis. It only shows whether “leptospirosis” was written on a death certificate. But CNN and CPI investigated two suspected leptospirosis deaths that were uncounted in the official Hurricane María death toll and appeared, based on interviews with families, neighbors and doctors to be related to the storm. Both men were relief workers or volunteers who spent considerable time in floodwaters, where the disease is known to spread.

One of the men, Daniel L. Vick, a 31-year-old father from Cayey, tested positive for leptospirosis at a local lab, according to his doctor. His medical records, provided by his family, show he was hospitalized with “fever/chills,” “nausea/vomiting” and “diarrhea,” which doctors say is consistent with the disease. Before his third and final hospitalization, family members and neighbors said, he was seen coming out of his house with jaundiced, yellowed skin—another sign of leptospirosis. His mother doesn’t understand why his death is uncounted.

“Maybe the government thought that the more people [that] died the worse it would look—that it meant they did a bad job responding to this tragedy,” Margarita Rodríguez said. “It’s incomprehensible. It seems like they don’t care. The only thing they care about is their image.”

Leptospirosis is very rarely fatal and can be treated with common antibiotics. It is carried mostly in the urine of rats and other animals. It can be ingested in drinking water or absorbed through cuts in the skin. Neither of the men whose deaths CNN and CPI investigated were given gloves, boots or prophylactic antibiotics, according to their families. Those simple measures can help prevent leptospirosis illnesses among people working in floodwaters, experts said.

In general, epidemiologists said that deaths occurring closer to the September 20, 2017 hurricane were more likely to be linked to the storm than those occurring in 2018. The 26 deaths labeled “leptospirosis” in Puerto Rico’s data occurred between September 24, 2017 and March 6, 2018. The majority of those deaths —21— happened before December 31.

For comparison, there were 11 suspected leptospirosis deaths in Puerto Rico the previous year, according to federal mortality data analyzed for CNN and CPI by an independent demographer.

Puerto Rican officials say they only are counting leptospirosis deaths as hurricane related if the illnesses were confirmed by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tests—and if the deaths occurred between September 20, the day of the storm, and October 20.

Daniel Vick’s mother, Margarita Rodríguez, holds a photo of her son, whose death was labeled “leptospirosis” in a database obtained by CNN and CPI. (Photo by John D. Sutter | CNN)

Vick’s death occurred on October 19, one day before that cutoff. It’s unclear whether his death was analyzed by CDC tests because officials declined to comment on specific cases.

Vinetz, from UCSD, called the one-month timeframe indefensible because it can take three weeks for leptospirosis symptoms to show up after infection and because hurricane clean-up (and the potential for exposure to leptospirosis that goes with it) continued for weeks.

“It’s not justified,” he said. “It’s probably too restrictive and it underestimates the numbers… I think it’s more probable than not it’s a political decision. It’s not justified by the medical science.”

Asked by CNN and CPI why so many more leptospirosis-labeled deaths appear in Puerto Rico’s mortality records than have been publicly acknowledged as storm-related, Dr. Carmen Deseda, Puerto Rico’s state epidemiologist said, “a lot of times the physicians don’t have access to the full records, and the laboratories may still be pending.”

Authorities are investigating the 26 cases shown in death records, Deseda said.

“Epidemic”

Several data sources suggest an “epidemic” or an “outbreak” of leptospirosis occurred in the aftermath of Hurricane María, but Puerto Rican officials won’t call it that.

On Friday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released its own statistics on leptospirosis deaths on the Caribbean island under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act. The internal CDC document lists 17 “confirmed and probable” deaths after the hurricane in which laboratory tests show leptospirosis was a factor—plus 25 additional “suspected” leptospirosis deaths that were in need of further lab confirmation.

In addition to the deaths, there’s also evidence leptospirosis illnesses increased.

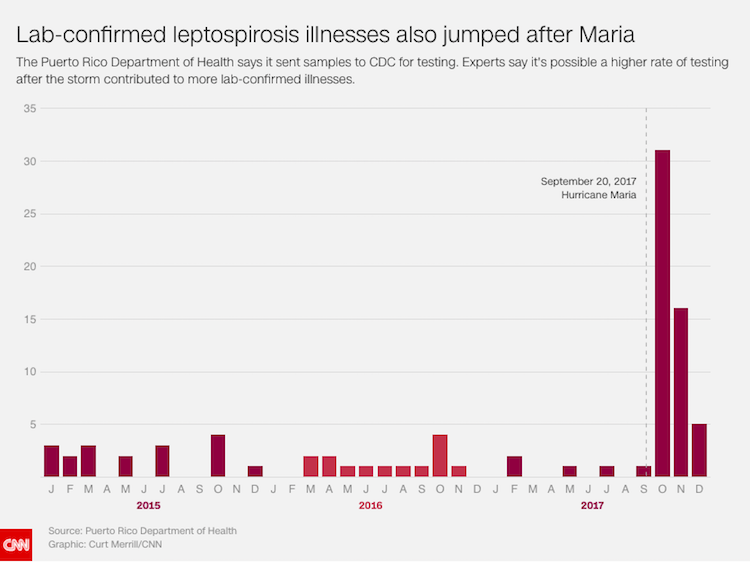

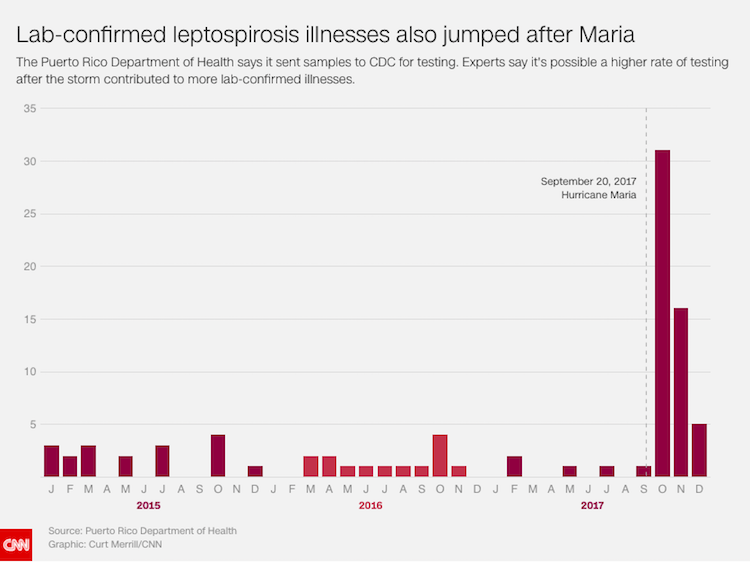

The Puerto Rico Department of Health told CNN and CPI there were 57 laboratory-confirmed cases of leptospirosis illnesses in 2017—54 of them after Hurricane María, which hit September 20. That’s a three- and four-fold increase in confirmed illnesses over the previous two years, according to the figures provided. Comparing months, the spike is sharper still—with 31 confirmed illnesses in October 2017 compared to four the year before; and 16 illnesses in November 2017, sixteen times more than the single confirmed illness in November 2016.

There is no internationally established threshold for declaring a leptospirosis “outbreak” or “epidemic,” according to epidemiologists, many of whom use those terms almost interchangeably. The CDC defines an epidemic, generally, as “an increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected in that population in that area.” Outbreaks often refer to “a more limited geographic area,” the CDC says.

Puerto Rican health officials have cited conflicting thresholds they say are needed to declare a leptospirosis epidemic. In November, Puerto Rico’s secretary of health, Dr. Rafael Rodríguez Mercado, told a local radio reporter “200 cases per week” were needed to make that declaration. Dr. Cruz María Nazario Delgado, a professor and epidemiologist at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus, told CNN and CPI that metric is “a bunch of nonsense.”

(On Monday, Rodríguez Mercado told CNN and CPI that he misspoke in that interview.)

In an interview with CNN and CPI on June 25, Deseda, Puerto Rico’s state epidemiologist, said that officials would need to see a “twofold” increase in cases to declare an epidemic.

Then on Monday, after CNN and CPI questioned these inconsistencies, Deseda released a statement through a spokesman paraphrasing the CDC definition of an outbreak or epidemic—and adding that it is “not appropriate” to compare the number of illnesses after the storm to previous years. That’s because officials were more actively looking for leptospirosis illnesses after Hurricane María and were doing so using different diagnostic tests, she said.

Three experts who reviewed data for CNN and CPI said it was clear from records that the government’s own threshold for an epidemic had been met —if not far exceeded— based on the fact that lab-confirmed illnesses more than doubled after Hurricane María.

Another way to assess the Health Department data, however, would be to look at both “confirmed” and “probable” leptospirosis illnesses, experts said. Both are at least partially confirmed by laboratory tests. Looking at the numbers that way shows at least a “twofold” increase when comparing October or November 2016 to 2017, but slightly less than two times the number of illnesses —1.6 times— when you compare all of 2016 to the following year.

Deseda, the state epidemiologist, said the Puerto Rico Department of Health did not have access to its own laboratory tests in the chaotic aftermath of the high-powered storm, and that adequate baseline data needed to declare an epidemic was not available.

“Leptospirosis is one of those diseases where it’s very hard to declare an epidemic,” Deseda said, “because, at that time, there was no testing we could do to validate or confirm the cases… It took about three or four weeks to send samples (to the CDC) because of the heavy impact of the hurricane, and the devastating impact on our communications and power supply.

“There was no way our laboratory was ready to put samples together. How could we declare an epidemic if we didn’t have that number [of confirmed cases] at that time?”

Officials responded to the illnesses urgently, she said, warning the public about the dangers of floodwaters, ensuring hospitals were supplied with antibiotics and telling physicians to treat signs of leptospirosis as if the disease had occurred, even if lab tests weren’t quickly available.

On October 22, Public Affairs Secretary Ramón Rosario Cortés told reporters that suspected cases of leptospirosis were “neither an epidemic nor a confirmed outbreak.” “But obviously,” he added, “we are making all the announcements as though it were a health emergency.”

“The Evidence Is Just Incontrovertible”

Seven experts —five epidemiologists and two medical doctors who specialize in the related diseases— told CNN and CPI that Puerto Rico’s mortality database and its own figures on confirmed leptospirosis illnesses suggest that an “epidemic” or an “outbreak” occurred.

The labels “epidemic” and “outbreak” are important, according to public health experts, because they can trigger increased surveillance for the disease and more robust efforts to prevent infection. They also help the public process the severity of the situation and take warnings seriously, which can lead to illness prevention and better treatment, experts said.

“In a situation like this, after a natural disaster, the important thing is to take control of the situation, not to hide the situation,” said Nazario, the professor and epidemiologist at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus. Officials, she said, had reason to believe there was a significant number of cases of leptospirosis after Hurricane María.

The leptospirosis cases should have been classified as an epidemic, Nazario said, adding that it is surprising that officials continue to be in “denial” that one occurred last year. Puerto Rican health officials had enough information to declare an epidemic even before CDC tests became available to them, she said.

“The Department of Health was not doing its job,” she said.

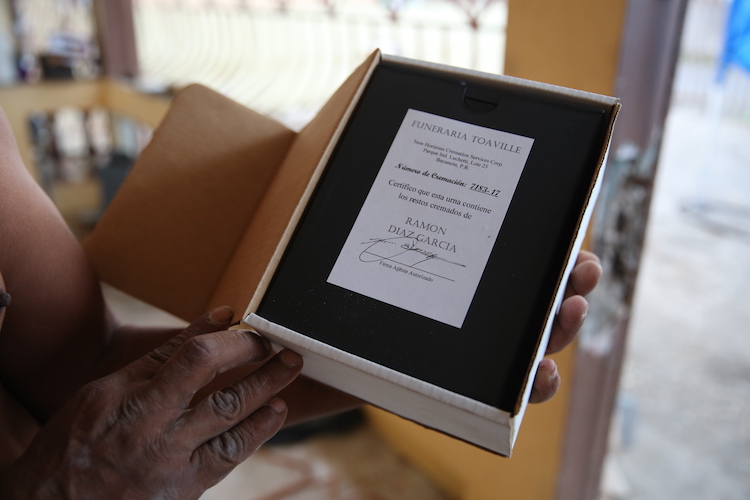

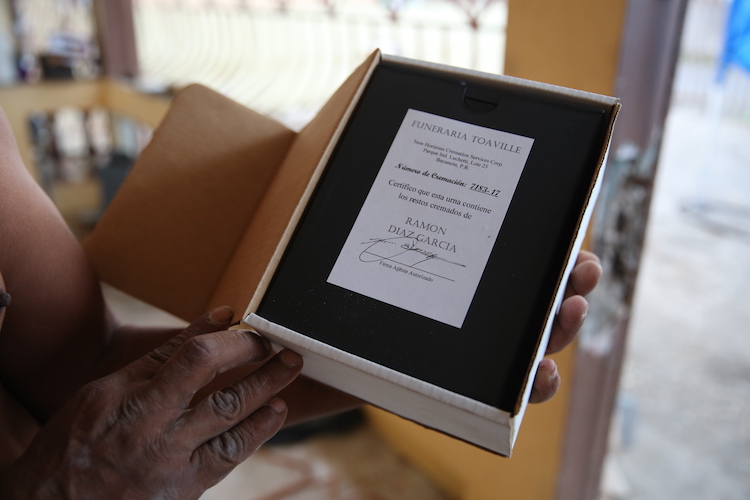

Luis Díaz García keeps his brother’s ashes in a box on his kitchen counter. He believes Ramón Díaz García’s death is related to Hurricane María. (Photo by John D. Sutter | CNN)

The data shows an “unrecognized epidemic,” said Dr. Albert Icksang Ko, a professor and chair of the Department of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases at the Yale School of Public Health.

“The outbreak of leptospirosis that occurred after Hurricane María and associated deaths were predictable,” he said. “Disasters, whether they occur in Puerto Rico or elsewhere throughout the world, are triggers or drivers of leptospirosis… It really emphasizes the challenges we have in addressing leptospirosis public health issues in Puerto Rico,” he added. “This information should have been public and I’m surprised you had to sue in order to get this information.”

“The real question is ‘why?’” said Dr. Lemuel Martínez, an infectious disease specialist in Manatí, Puerto Rico. “If they had the data, why would they not declare [an epidemic] at the time?… This is not a matter of opinion. The data is there. Why would they withhold it?”

The numbers are stunning, said Vinetz, the UCSD professor. “The evidence is just incontrovertible that there’s something going on, something important going on,” he said. “Puerto Rico not calling this an epidemic , [one] that’s not even the government’s fault, is a political decision. It’s piffle not to call this an outbreak or an epidemic.”

Several experts stressed that leptospirosis is under-researched. Physicians often miss or misdiagnose the disease, which has symptoms that mirror other diseases like flu and dengue, including “fever, headache, chills, muscle aches, vomiting/diarrhea, cough, conjunctival suffusion, jaundice, and sometimes a rash,” the CDC says. Untreated, according to the CDC, a person “could develop kidney damage, meningitis, liver failure, and respiratory distress.”

The other experts saying an epidemic or outbreak should have been declared were: Jonas Brant, a professor and epidemiologist at the University of Brasilia; Dr. Melissa Marzán Rodríguez, an epidemiologist and professor of infectious diseases at Ponce Health Sciences University, in Puerto Rico; and Claudia Muñoz-Zanzi, an epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, who said this is the “definition” of an outbreak.

“We need to increase awareness about leptospirosis and about these outbreaks, and [about] the need to do more research in order to detect these outbreaks as early as possible” and to say how best to respond, said Muñoz-Zanzi. “Without [public officials] declaring outbreaks, we cannot do that because we don’t have the data we need to establish those recommendations.”

Worldwide, the disease is estimated to contribute to more than one million illnesses and nearly 60,000 deaths per year, the CDC says.

Two additional experts said an outbreak could have been declared, but would not go so far as to say that it should have been declared by Puerto Rican authorities without better baseline data and without understanding exactly what officials did and did not know at the time.

Dr. Brenda Rivera García, a former state epidemiologist in Puerto Rico, said there is clear baseline data available for officials to judge whether an epidemic occurred. In retrospect, she said, there was a significant increase in cases in a short timeframe, but she’s unsure if the Health Department had all the necessary information at the time to declare an epidemic.

“Almost non-existent”

CNN and CPI investigated a total of four deaths labeled in government data as having been related to leptospirosis that were uncounted as part of the Hurricane María death toll.

After interviewing relatives and neighbors, consulting with experts on the disease and, in one case, reviewing hospital records, at least two of these uncounted deaths appeared to be related to Hurricane María, based on CDC-established criteria for disaster deaths.

At least one case appeared to be unrelated to the storm.

Jose A. Sánchez Vázquez, 58 was hospitalized before Hurricane María hit, according to Ana Sánchez, his sister. He died four days after Hurricane María, records show. Because he got sick before Hurricane María made landfall, Ana Sánchez does not consider his death storm-related.

In Bayamón, a suburb of San Juan, Puerto Rico’s capital, Ricardo A. Cotto Rodríguez, 48, who was known in his neighborhood for his humor and for being the fanatic water boy for the Vaqueros, the local basketball team, died on November 17, records show. Relatives told CNN Cotto was essentially bedridden after the storm and that his bed sores became infected.

He was hospitalized after he fell and became stuck in the shower, they said, when there was no electricity in the area. Gilberto Rodríguez Quiñones, his cousin, said his death appears to have been related to Hurricane María because of that fall, which he said occurred in darkness, without power. But it was unclear how he may have contracted a waterborne illness.

The government database lists “leptospirosis,” “chronic ulcer of skin” and “obesity” among the contributors to Cotto’s death. His death certificate says leptospirosis “possibly” contributed.

Ana Sánchez says her brother’s death, labeled “leptospirosis” in government records, is not related to Hurricane María. (Photo by John D. Sutter | CNN)

In two other cases, however, family members and neighbors of the deceased described circumstances that medical professionals say are consistent with leptospirosis.

Both men were working in relief efforts after the storm, putting them in contact with flood waters that, according to experts, would increase their chances of infection.

And neither, according to family members, was given gloves, boots or prophylactic antibiotics, which public health experts say can be used to prevent leptospirosis infection.

Deseda, the state epidemiologist, said relief workers were given preventative help. Officials adequately publicized the risks of leptospirosis, she said, and antibiotics were available at hospitals. When pressed, she did not state clearly whether drugs were used preventatively.

She defended Puerto Rico’s efforts to warn the public about the disease, saying she appeared on television and the radio warning people to stay away from possibly contaminated waters and trash—places where urine from rats and other animals may have been found.

Martínez, the doctor in Manatí, Puerto Rico, said communications from the Health Department about leptospirosis were “almost non-existent, at best.” They largely focused, he said, on denying an outbreak was occurring and telling physicians to treat patients regardless of lab tests.

“It shocked me”

In Toa Baja, Luis Díaz García, 55, told CNN and CPI that his younger brother, Ramón Díaz García, 52, was generally healthy before the storm. He suddenly became sick and then disappeared after spending weeks volunteering with cleanup efforts, Luis Diaz said. The family spent a month in agony, not knowing what had happened before a relative contacted the Bureau of Forensic Sciences in San Juan. The database shows Ramón Díaz’s death on October 26 was reviewed by the Bureau of Forensic Sciences, which did not conduct an autopsy.

“Leptospirosis” is listed among the contributors to his death in the records.

“The pathologists told us that he had a strange color, that he looked yellowish,” Luis Díaz said. “They asked if he had hepatitis, and we said, ‘No, he was healthy.’”

Martínez, the infectious disease specialist, said yellow skin is a clear sign of leptospirosis, especially when it’s accompanied by acute fever and occurs after a storm. “If someone turns yellow after a hurricane, that’s leptospirosis unless proven otherwise,” he said.

Puerto Rico’s Bureau of Forensic Sciences is authorized to classify deaths as hurricane-related. Yet Ramón Díaz’s name does not appear on Puerto Rico’s list of 64 hurricane victims.

Ramón Díaz did not have identification on him when he went to the hospital, his brother said. Forensics workers told Luis Díaz that if the family hadn’t contacted them his body would have been cremated in a matter of days and would have remained unidentified, he told CNN and CPI.

“It shocked me,” Luis Díaz said.

“He was cool with everyone. He would help anyone who needed it,” Luis Díaz said of his brother, one of 13 siblings. “That guy would put you to sleep talking and talking, telling jokes!”

Ramón Díaz was living with him at the time of the storm, Luis Díaz said. Ramón Díaz’s room is now hauntingly empty. The blades of a fan are motionless on the floor. A clock that hasn’t worked for years hangs on the wall, stuck just after 4pm. A mattress is crumpled in the corner.

Luis Díaz struggles to understand why his brother remains uncounted.

“I don’t know what to tell you,” he said, appearing choked up by the question.

He keeps his brother’s ashes in a box on the kitchen counter.

“He Sacrificed Himself”

Daniel L. Vick, the young father in Cayey, also is uncounted.

The 31-year-old, who loved the beach, karaoke nights and watching his seven-year-old dance salsa, spent his days after Hurricane María wading through floodwaters to help neighbors as an employee of the city of Cayey, relatives said. His death on October 19, which Puerto Rico mortality records label as “caused” by “leptospirosis,” is not counted as a hurricane death.

The physician who certified his death, Dr. Julio García at Centro Médico Menonita de Cayey, told CNN and CPI that a local laboratory test indicated he had leptospirosis.

Before his third and final hospitalization, family members and neighbors said, he was seen coming out of his house with jaundiced, yellowed skin—another sign.

Margarita Rodríguez said her son was in “perfect health” before the storm.

Officials declined to comment on the deaths of Vick or Díaz beyond saying that they had not been officially classified as related to Hurricane Maria. One of the two cases —either Vick or Díaz— was confirmed by laboratory tests as having been caused by leptospirosis, said Deseda. She refused to say which of the two it was, however, adding that the lab-confirmed leptospirosis death was not counted as hurricane-related because of the date it occurred.

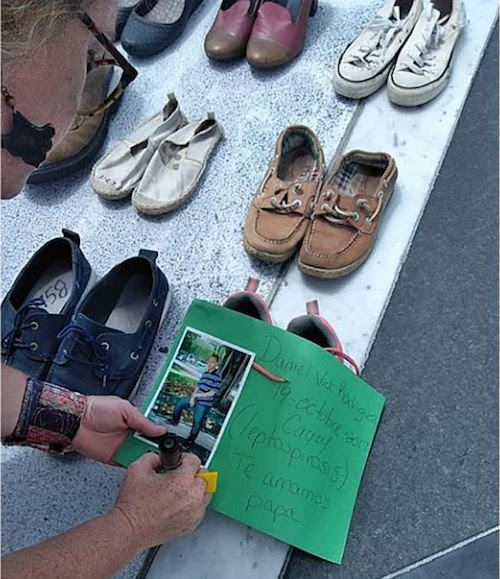

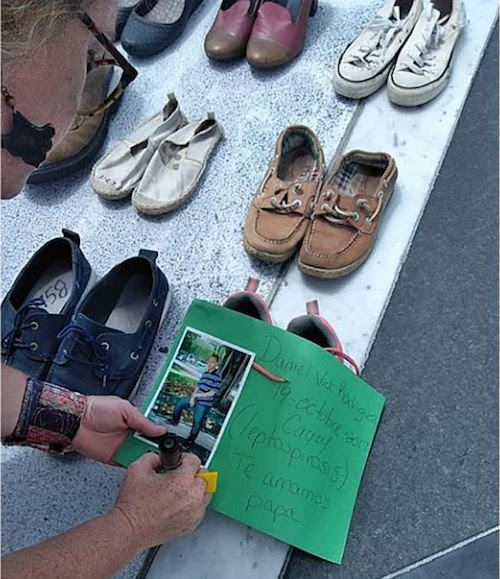

Daniel L. Vick’s family left a pair of his shoes at a memorial for uncounted victims of Hurricane María in San Juan. (Photo courtesy of Margarita Rodríguez)

Rodríguez said she pleaded with her son to stay alive.

“You have to be strong,” she recalls telling her son in the hospital. “We need you here, for your daughter, for your wife, and to keep helping your community. We need you here.”

“You could see tears running down his face” as medical professionals intubated him, pushing a tube down his airway so he could continue to breathe, she said in an interview. “You could tell by looking in his eyes that he didn’t want to close his eyes, to let himself go.”

“He sacrificed himself,” she added. “He gave everything … He should be considered a hero.”

“I just want him to be remembered,” she said.

Margarita Rodríguez will remember her son as a shy, kind, caring and thoughtful man, a man who loved his family and loved his work, who rarely stepped into the spotlight but whose worth was measured in all he quietly did to help others, especially after María.

His widow, Ingrid Nieves García, 29, left a pair of his shoes at an impromptu public memorial for victims of Hurricane María at the Puerto Rican capitol building in San Juan.

In early June, mourners placed thousands of empty shoes near the steps to represent uncounted victims.

Leaving Vick’s shoes there was important “because I never had the space or moment to say goodbye in his funeral. It was just not in me to do that back then,” she told CNN and CPI. “I believe the moment I brought his shoes [to the memorial], which were the last thing I had left from him, it helped me to let go, to say goodbye. It was only then when I finally let him rest.”

After his death, a psychologist told Daniel Vick’s daughter that her father is in heaven, an angel watching over her—that God needed him to be up there with him, his mother said.

“Maybe later,” a neighbor said, “she will understand what happened.”

Cristian Arroyo, Michael Nedelman, and Laura Moscoso contributed to this report.