Hurricane María damage to Puerto Rico, September 29, 201 (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Public Domain)

When I had the opportunity to go on a reporting trip to Puerto Rico with my graduate journalism program four months after Hurricane María plowed through the island, I knew I had to take it. I was overcome by a deep-rooted sense of duty to the home of my grandparents and a desire to stand in solidarity with those living on the island. Although I didn’t really know anyone there besides some extended family members, I felt an ineffable connection to the people who had braved the worst storm the island had seen in 90 years. But an interaction in a café in San Juan made me question whether I had any business being there at all.

I was writing a story about how restaurants were affected by the lack of produce on the island in the wake of the hurricane. A friend of mine from the island instructed me that some businesses resorted to using frozen plantains because plantain farms were destroyed during the storm. I wondered how the substitution would disrupt the island’s food culture, especially since tostones and plátanos are staples in the Puerto Rican diet.

I found a café that sat in the touristy part of the city, mere blocks away from the Balneario El Escambrón beach. It looked as though a bougie coffee shop had been transplanted to the island from New York City or Chicago. Twinkle lights dangled from the ceiling and roped around the walls. A sign written in pink chalk above the register read: “No oranges since after the hurricane.”

“Perfect,” I thought.

I chatted with a café worker as I decided between which sandwich to order. He was from Venezuela and said he had fled Nicolas Maduro’s rule. I told him my dad was Puerto Rican—a crutch I often use to clue Latinos in that I was not just another white colonizer, even if my pale skin suggested otherwise.

“Do you want to eat something that’s not listed on the menu?” the café worker asked after watching me study the blackboard while trying to gather the courage to interview him.

Oh yeah.

Eventually he brought me pernil and rice and beans, the best meal I’d eaten on the 10-day trip. I savored every bite as I waited for the lunch rush to dissipate. I wanted to catch the café worker at a moment when he was the least distracted and most open to speaking with me. Yet when I revealed that I was a journalist who wanted something from him, the once amicable deliverer of pernil balked at me.

“No, you can’t record here or mention the café,” he said. “They’re always sending young journalists like you down here to get the story and you guys don’t realize that this has been going on forever.”

His skepticism regarding outside media was not unwarranted. It’s true that before María, the mainstream media hadn’t been really following Puerto Rico, even though the island has been mired in economic strife and political turmoil for years.

The café worker’s words hit me like ocean waves on the sandy shore, exposing both the imposter syndrome I felt about not being “Puerto Rican enough,” as well as my guilt about being one of those journalists who parachutes into a community during a time of crisis with little regard for or understanding of the environment.

I was haunted by a torrent of questions. Did I, as a half-Puerto Rican journalist with butchered Spanish, have a role in telling Puerto Rico’s story? Did my classmates —most of them white with limited knowledge of Puerto Rico’s history and culture— have a right to report on the mental health crisis and ask people to relieve their trauma after only being on the island a few days? And if we did, how could we go about reporting in the most informed, empathetic way? Would our work elevate Puerto Rico and the work of the Puerto Rican journalists who came before us? And who would continue to focus on the Puerto Rican people and their trials once we went back to our cozy lives of higher education?

There was no doubt that my classmates and I were indeed parachuting in and out of Puerto Rico. The program directors stressed that the trip wasn’t a vacation —and it certainly didn’t feel like one— but I could see how it might have looked like one. And that made me uneasy.

The politics of journalism are complicated, and when it comes to Puerto Rico’s colonial relationship with the United States, these politics become even more convoluted. Who gets to tell the story of Puerto Rico? Me? I wasn’t so sure, so I chatted with a variety of Puerto Rican journalists living both stateside and on the island in search of an answer. I’d let them determine my fate.

***

AJ Vicens, a Puerto Rican journalist at Mother Jones and current Knight-Wallace Fellow, says he has tried for years to get the magazine to do stories about his homeland. Since 2015, Vicens said he has pitched pieces about police brutality and the fiscal crisis on the island, but “they just really didn’t see an interest there. Relatively speaking, Hurricane María had to rip Puerto Rico in half for it to get on the nightly news,” he said.

Although there were brief mentions of the island before last hurricane season, Vicens noted that the media collectively treated Puerto Rico’s debt crisis like the debt crises of Greece and Argentina—as if it was unfolding in some faraway land.

A mixture of clouds and smoke make an ominous background for the Monacillo power station following an explosion that cut power off from over 10 municipalities in February, as workers struggle to rebuild the island’s energy infrastructure. (Photo by Elizabeth Beyer)

Crisis journalism, for the most part, does not require the cultural and historical knowledge or knowledge of Spanish that more in-depth sustained kinds of journalism might. “Immediately after the hurricane, the story is —I don’t want to say it’s not as convoluted— but it was about reporting the facts,” said Luis Ferré-Sadurní, a reporter for The New York Times. “How many people are without power? What happened in this town? What are people saying? It doesn’t take someone Puerto Rican to be able to reconstruct what happened.”

But after reporting on the immediate effects of Hurricane María, many journalists packed their bags and left. “Here we go again with the crisis journalism,” said Ilia Rodríguez, a Puerto Rican journalism professor at the University of New Mexico whose work primarily focuses on diversity in the newsroom.

But what happens to Puerto Rico when no one is looking, when the cameras are packed up and journalists return to their desks?

“The hurricane changed the rules of daily living,” Rodríguez said. When she visited her home for the first time in several months, she felt like an anthropologist observing a culture that had wholly changed. “You hear these stories and they’re always focused on the more dramatic things. The day-to-day details are a different perspective.”

She discussed how the crumbled infrastructure changed the way people drove and how the lack of electricity affected how Puerto Ricans went about their lives. These are the stories that often go overlooked, because they require money and knowledge of Puerto Rico’s historical context.

A news model that focuses on the histrionic to generate audiences’ interest has failed Puerto Rico as hurricane recovery stories were (and still are) framed as Trump stories. Julio Ricardo Varela, the publisher/founder of Latino Rebels (whose outlet graciously published this story for me), was one of the first Puerto Rican journalists to go on the air about Puerto Rico post-María because networks couldn’t get to anyone on the island immediately following Maria. When MSNBC brought him on its network to discuss happenings on the island, Varela and anchor Kier Simmons held divergent ideas for the direction of their conversation. “They wanted me to talk about Donald Trump and I said, ‘I’m not talking about that,’ There’s an underreported death count. Everyone should be focusing on this issue,” Varela said.

Indeed, the first question Simmons asked Varela was his opinion on Trump’s tweet that “Puerto Ricans want everything done for them.”

It makes sense that the media has focused on the most sensational aspects of the aftermath of María because the media is increasingly becoming a business that relies on clicks. El Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (CPI) and the Miami Herald reported that Puerto Rico —which received significantly less media attention than Texas after Hurricane Harvey or Florida after Hurricane María— became privy to heightened attention every time Trump posted an inflammatory message concerning the island on his Twitter account.

Andrea González-Ramírez, a news and politics reporter at Refinery 29, said, “I understand from the business perspective, sometimes it’s very difficult to sell a story about Puerto Rico. With the administration and everything that’s happening that affects a larger group of people and because of the political relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico, there’s not going to be an effort to prioritize that content.”

Despite the feeling that she’s mostly screaming into the void, González-Ramírez is working tirelessly to keep Puerto Rico in the news. She is constantly pitching stories about Puerto Rico to her employer and even started the following Twitter thread when she sensed that not enough people noticed the results of the May Harvard study, estimating that approximately 4,645 Puerto Ricans died in the aftermath of María.

Since the news cycle and Twitter dot com apparently already forgot about the 5,000+ people who died in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, I’m going to spotlight the stories of our dead. #4645boricuas

— Andrea González-Ramírez (@andreagonram) May 30, 2018

Even when journalists from outside Puerto Rico were on the island doing the reporting, however, their gaffes diminished the island’s plight. Luis Trelles, a professor at the CUNY School of Journalism and producer of the NPR program Radio Ambulante, said that some journalists came in with preconceived notions of the story they expected to get. While he was reporting on the island, he crossed paths with a stateside journalist who was really interested in writing about political unrest and riots because he’d been in another situation where that happened. “He was convinced it was going to be a big story,” Trelles said. “There were some minor outbreaks here and there, but that wasn’t the major story of PR after the hurricane. He was a veteran journalist. A huge national outlet sent him. He was kind of just waiting in his hotel room for civil unrest to break out so he could have the story he wanted to cover, not the actual story on the ground.”

Though accounts like these seem isolated and innocuous, journalists’ lack of awareness can not only compound Puerto Ricans’ distrust of the media but also overlook their struggles. Bianca Padró Ocasio, a reporter at the Orlando Sentinel, was shocked to see female anchors wearing heels and dresses in the middle of a disaster zone. “I was so resentful of it because I was like no, get out there, just talk to people. And a lot of people didn’t do that in the beginning. Many people stayed trying to get the government’s responses, which are important and definitely has a role. But it was frustrating to see that.”

***

Nearly everyone has scattered from the ABC 7 studio in Chicago after the Sunday morning broadcast. Mark Rivera, the station’s weekend Eyewitness News anchor, studies the beverage options in the vending machine. When he notices me, he grins and gives my hand a hearty shake. It’s hard to believe this guy’s been up since 3am.

Like me, Mark is half-Puerto Rican. In the weeks following María, he used his personal experience to elevate the situation on the island. His family lives in Yabucoa, Puerto Rico, a region hit especially hard by the storm. When we spoke in late April, his grandparents and his 101-year-old great-grandmother still hadn’t gotten their power restored. Rivera has shown pictures of his family on air to try to put faces to what may seem like an abstract atrocity to his viewers.

“It’s just really frustrating to do everything you can here and to know it’s taking them a long time to get the services they deserve,” said Rivera.

Also like me —and many other first- and second-generation diasporic Puerto Ricans— Rivera’s Spanish is mal. When he was younger, he’d hear it spoken at family parties, but he wasn’t raised bilingual. Now he’s contemplating buying Rosetta Stone.

Does he think that a journalist can effectively report on Puerto Rico without knowing Spanish?

“I think you cannot speak the language and see ten thousand blue tarps as you’re flying in and realize ‘Oh this is a big problem. Oh, these people don’t have the services right now that any other American would be crying out for in protest,’” he said. “I don’t think you necessarily need to speak the language to look at someone who is putting their house together after a windstorm blew in all the windows and knocked off the power and they don’t have water. I don’t think you necessarily have to speak that language to understand that their life is totally destroyed. I think you can describe that in English and Spanish by looking at it, looking at the person picking up pots and pans that are on the ground or trying to catch rainwater in a basin as they’re waiting for the next shipment from the National Guard.”

He cited CBS correspondent David Begnaud as the epitome of this phenomenon: someone who didn’t know Spanish, had never stepped foot on the island previously and was able to do important and critical journalism.

Puerto Rico needs more trucks & drivers who can deliver food & water, according to Governor @ricardorossello pic.twitter.com/2fOSAk4IwP

— David Begnaud (@DavidBegnaud) September 27, 2017

***

As inspired as I was by Rivera’s sentiment that humanity can transcend language barriers in reporting, I was not fully convinced.

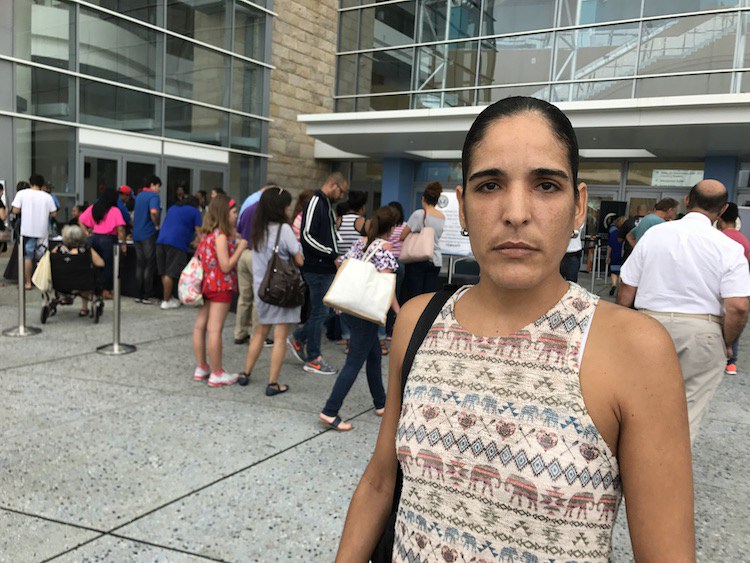

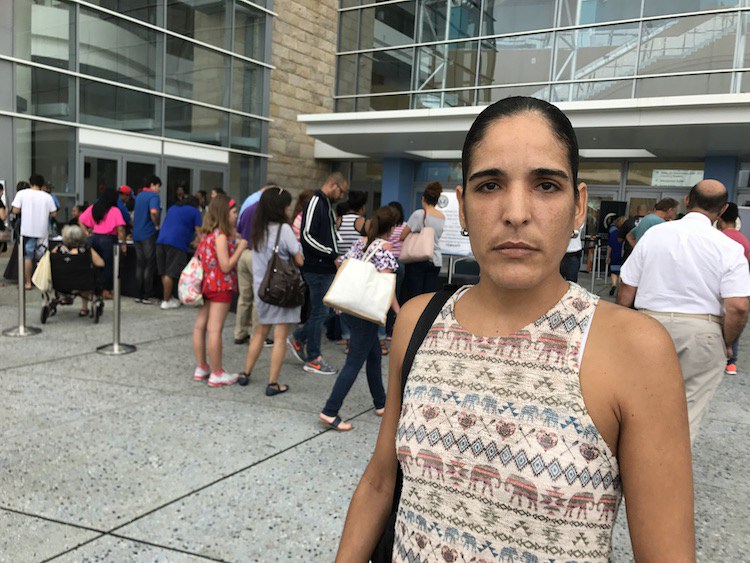

On day four of our reporting trip on the island, we visited Casa Pueblo, a non-profit community-based organization that (among many, many other things) has been working to provide solar power to the residents of Adjuntas. After the visit, we had free time, so my classmate Jessica and I decided to do our own reporting at the FEMA office a couple of blocks away. Jessica and I were working about a story about FEMA’s transitional housing program in Chicago for the CPI.

The lines of people waiting to receive aid stretched outside the door. Jessica, who spoke Spanish, did not stand out among them. I, on the other hand, did.

I did not want to take advantage of Jessica as a Spanish-speaking resource, as some of my other colleagues had throughout the course of the trip, because we did not have a fixer. And so, we went our separate ways.

Time felt frozen during the minutes I spent standing around awkwardly, shifting my weight from foot to foot, contemplating who to approach about the loss of their homes and livelihood within minutes of accosting them. In the end, it was an older, grandpa-type man with kind brown eyes and a straw fedora who approached me and asked me what I was doing at the FEMA office. His English wasn’t great.

“Talk to my wife, Rosario,” he said. “She speaks better English.”

Indeed she did. Moments later, a weary woman with a handful of folded FEMA applications and instructions emerged.

“Mi español es muy mal,” I’d preface.

“You speak Spanish like my granddaughter,” she laughed. It turns out her granddaughter was also a journalist who lives in Boston.

By the end of the conversation, I had come no closer to understanding the extent of her frustration of having to wait several months for FEMA to give aid for a new roof. But, with typical Puerto Rican generosity, she had offered me a place to stay the next time I visited the island.

“I’ll cook for you,” she said as she scribbled down her physical address and email in my reporter’s notebook. I thought of my own grandma who showed her love through sprinkling adobo spice on every meat you could imagine, and the Goya products that littered her kitchen cabinets.

The line of people praying in the FEMA office in Adjuntas had important stories, but there’s only so much a journalist can learn from observing. Power is derived from allowing people to speak their truth in their primary language. And as AJ Vicens pointed out to me later on, there’s a “certain baggage that comes with forcing people to speak English.” It’s a practice rooted in colonial tradition.

The reasons Begnaud was able to produce the incredible journalism that earned him the nickname “patron saint of Puerto Rico” include resources, but also the nature of his journalism. Though Begnaud was initially unfamiliar with the island, he didn’t simply parachute in, grab a compelling story and leave. He became a lifeline for the Puerto Rican people when they had nowhere else to turn for their news. He kept them updated on the whereabouts of their families. And even when Puerto Rico had long escaped the news cycle’s attention, he continued to tweet stories about the island.

Begnaud’s journalism was not simply crisis journalism. He stuck around and was with the island for the long haul, which many Puerto Ricans appreciated.

A woman dances at the site of a proposed waste incinerator in Arecibo. The incinerator, if approved, will produce energy for Puerto Rican residents but could also pollute the surrounding communities. (Photo by Elizabeth Beyer)

***

Nonetheless, there are drawbacks that accompany the benefits of being a Puerto Rican journalist reporting on Puerto Rico. Take the case of Ferré-Sadurní, who works for The New York Times’ Metro desk. After Hurricane Irma barreled through the Caribbean and the southern U.S., Ferré-Sadurní petitioned his editor to send him to the island. The trip would only cost $128 for airfare, he told him. He had lodging (his family) and transportation (his own car). At the moment, the Times didn’t have anyone in the Caribbean covering the storm so his editor told him to get on the plane immediately.

Ferré-Sadurní traveled around the Caribbean for a week, writing stories from Puerto Rico, St. Thomas and the U.S. and British Virgin Islands. He was about to book his flight back to New York when ominous forecasts about Hurricane María emerged. His editor told him to stay one more day to “see what happens, just in case.”

“María kind of caught outlets off guard and it was really hard to get anyone down there,” Ferré-Sadurní said. “I was the only reporter for the Times in Puerto Rico when the hurricane hit. And even three or four days after the hurricane, they couldn’t get anyone down because the airport was closed.”

Hundreds of people lined up for gas and diesel for generators in Puerto Rico #Maria @nytimes pic.twitter.com/IkVhQre1tD

— Luis Ferré-Sadurní (@luisferre) September 22, 2017

Eventually Frances Robles of the Times, who also grew up on the island, was able to make her way to Puerto Rico and filed several important stories from there.

Ferré-Sadurní stayed on the island for 40 days, walking through some of the very streets and neighborhoods he grew up in, the once familiar becoming foreign. While doing the reporting, he didn’t really process what he was seeing, but at night “when everything had quieted down a bit,” he tried to understand the images of trees blocking the highways and flooded houses without roofs.

“I was emotionally, physically and psychologically drained. I told my editor, ‘This is the end for me. I want to head back to New York.’”

And back to New York he went. He took a couple of days off, burrowed away from people so he could attempt to process what he saw. But when he did return, he not only resumed his position at the Metro desk, but he also assumed the roles of helping out reporters who were going down to Puerto Rico.

For Puerto Rican journalists, a higher sense of responsibility propels them to report on the island. “I’m from Puerto Rico and this was happening to my island. This was my opportunity to show the world what was happening there and make sure that it doesn’t happen without a light being shined on it,” Ferré-Sadurní said.

***

Padró Ocasio of the Orlando Sentinel thought a lot about her homeland last year during hurricane season. She had recently moved to Orlando originally to be closer both geographically and culturally to Puerto Rico (Florida has the second-highest concentration of Puerto Ricans after New York), where she had grown up. Three months after she started working at the Sentinel, Hurricanes Irma and María struck.

“The week before Hurricane María, it was Hurricane Irma here in Florida. I was sleep-deprived. After María, I remember I didn’t sleep at all because I was thinking of my parents and grandma who were in Puerto Rico,” Padró Ocasio said. “I’m listening to the radio station, pretty much the only one that was working at that point and it was very difficult, because you’re imagining all these possibilities and all you want to do is be there. I cover breaking news, so we do a lot of public safety and crime [stories] and I couldn’t focus on any of it.”

The day after Maria, she worked on a story about how Puerto Ricans were responding to the hurricane in Florida, and shortly thereafter, she was sent down to the island. Because Padró Ocasio is the only bilingual reporter for the Sentinel (it has a sister paper published in Spanish called El Sentinel), she was able to do the bulk of the reporting regarding Puerto Rico for the paper, even though it fell out of the bounds of her position as a breaking-news reporter.

Volunteer Ashley is showing us how to pack food boxes which will be sent to #PuertoRico pic.twitter.com/Im2Fw1Bm5G

— Bianca Padró Ocasio (@BiancaJoanie) October 15, 2017

But Padró Ocasio only reported in Puerto Rico for a week, and she said Puerto Ricans on Twitter trolled her for it. According to her, they’d leave resentful comments about the short time she stayed there and asked her why she didn’t visit certain communities.

“People were just so upset at everything that was happening and the fact that the spotlight was on Puerto Rico [and scrutinizing] who’s doing it right and who isn’t,” she said. “I felt really helpless because these people don’t know me. They didn’t know how much it meant to me when I was there. When I came back, it was horrible because I wanted to go back immediately.”

***

Omaya Sosa Pascual, co-founder of the CPI, broke the story about the Hurricane María death toll being underreported last September. Sosa has been embroiled in lawsuits with the Puerto Rican government for death count data for months.

“You just get tired of hearing all these terrible stories some days you just don’t feel like calling another family of another dead person and hearing the whole story,” she said. “Each story is unique. Maybe for you [as a journalist] it’s story number 70, but for them they’ve been waiting for this call to talk about what has happened to them.”

The CPI is doing important journalism, but in order for their stories to get out, they collaborate with news organizations outside of Puerto Rico (like Latino Rebels and Latino USA, both part of Futuro Media).

Last September in Puerto Rico, Nilka Fontánez (pictured here) told the CPI that she could get medical help for her 79-year-old father, Pedro Fontánez. (Photo by Omaya Sosa Pascual)

“There’s a lot of nuance in that coverage but because they pretty much create forums for alternative and interpretive communities, their impact on national discourse can be limited,” Ilia Rodriguez said. “It’s the same thing with Puerto Ricans in mainstream organizations; you can make a difference but if you have three or four journalists, it’s not going to change. They’re journalists, not the owner of the organization.”

The lack of clout can make organizations such as CPI a bit vulnerable. Some journalists have said The New York Times got credit for breaking stories it did not actually break, like one about the death count.

“The Times does amazing work and has amazing reporters, obviously,” Vicens said, “but so often, the Times will come into a story that’s already been done, do a little bit extra and then claim that it’s theirs. And because of the scale of what they do, everyone’s like, ‘look what the Times did.’”

Still, even if reporting from Latino organizations may be overlooked, there’s no doubt that they serve to fill a major void.

For instance, Varela said he is able to speak his mind and make editorial decisions, because his media organization is not bound by traditional restrictions.

“Puerto Rican journalists do a better job covering Puerto Rico. I’m in a position where I can say that because I work for an independent media company and can be more of a media critic. I don’t work for the New York Times or the WashPo or CNN so I can say when they missed a couple of things,” he explained.

Varela also doesn’t feel that Puerto Rican journalists should hide their pride or identity.

“They call journalists who want to shake up power, activists [as a derogatory term]. I see myself as a journalist that cares deeply about where he comes from and cares deeply about the stories that need to get elevated about Puerto Rico.”

***

As I neared the end of my reporting journey, I was still wrestling with questions of identity and whether only Puerto Ricans can effectively report about the island. Not exactly, but the key takeaways from my inquiry show the necessity of elevating the island in our journalism.

“We must put Puerto Rico first,” Varela said.

And while Varela was born on the island, he doesn’t subscribe to the notion that diasporic Puerto Ricans are not real Puerto Ricans.

“Don’t let anyone tell you you’re not a real Puerto Rican,” he told me after a live taping for the In The Thick podcast, which he co-hosts with Maria Hinojosa.

For him, it’s all about getting past the different factions that exist among Puerto Ricans and uniting in our prioritization of the island.

A man cooks in the outside kitchen of a roadside restaurant in Loiza, an island community built by people who were once enslaved. The residents of Loiza have been fighting for sustainable tourism since before the hurricane and have struggled to rebuild following María. (Photo by Elizabeth Beyer)

Identity is very important when it comes to reporting/the politics of journalism, but plays less of a role than I had originally thought. If we focus too much on identity, that could be limiting for the Latinos who work in non Latino-centric media outlets. On the other hand, the reason we focus on identity so much is because there’s a dearth of Latino journalists in these positions.

“I want to see more Hispanics in our positions because if we’re going to be the majority in this country, we should be reflected. Absolutely,” Ana Belaval of WGN News said. “But if my station wants to cover it with Ben Bradley, God bless it. If I can’t go because my kid has a birthday party, send Lourdes Duarte, who’s Cuban. Who gives a crap? Get it covered. It’s like thinking that I can’t cover the Art Institute because I grew up in Puerto Rico. It’s like saying I can only cover stories in Pilsen because that’s where I’m going to be able to understand. I did the crossover [from Spanish-language to English-language television] because I don’t have to do all the stories about Puerto Rico. I don’t have to cover just what happens in Pilsen and Little Village and to the Latinos in Aurora. I want people to see my face with my voice covering a cider brewery. The hell do I know about cider? But you don’t know anything either.”

Ferré Sadurni echoed these sentiments.

“At the end of the day, it’s about having smart reporters asking the right questions,” he said. “I learned a lot from seeing my American colleagues that parachuted in and were able to report amazing, incredible stories in one or two days on an island they had never been to just because they were brilliant reporters who had a methodology because they’ve been doing this, whether it’s parachuting into school shootings and any small town in the last couple of years in the United States or war zones or other disaster zones. A lot of those reporters were there for those sorts of events. And they were kind of seasoned entrepreneurs for what happened in Puerto Rico.”

***

Gwen Aviles is a freelance journalist based in Brooklyn. She covers arts and culture, media trends and Puerto Rico. Her Twitter handle is @gwenfaviles.