“Yo tengo que hablar por ellas, las que ya no viven”

January 2018, La Nacha

La Nacha

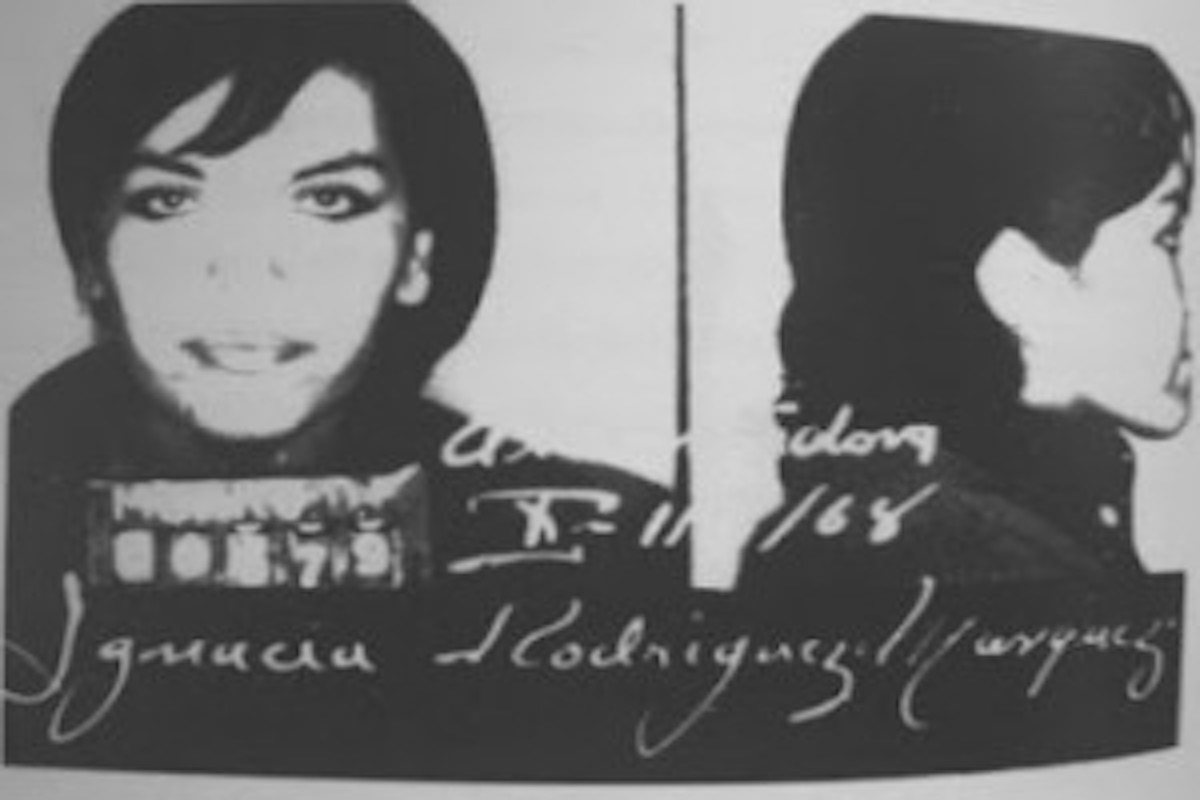

When the Mexican military entered the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) on September 18, 1968, Ana Ignacia Rodríguez Márquez, along with 42 other female students, was detained and transported to a men’s prison located in the northeastern part of Mexico City, known as the Black Palace of Lecumberri, where she was interrogated —without reprieve— and released 72 hours later. Her arrest came at the will and consent of the public prosecutor’s office.

Ana Ignacia was 21 years old and had just completed her course work in the School of Law. She was still writing her thesis at the time of her arrest.

During the interrogation, when asked about her travels to Cuba, or studying Marx and Lenin theory (which were part of the law school curriculum), the conspiracy theory that the Mexican government portrayed of the student movement —that it was a communist plot organized outside of Mexico— was being woven. The interrogators gave her an alias: La Nacha.

Because of this experience and her commitment to the student movement, one who defended the autonomy of her university and fought for a democratic Mexico, Ana Ignacia was transformed into La Nacha. With time, this name became a term of endearment.

1969 Mug shot provided by La Nacha.

Born in Taxco, Guerrero, La Nacha moved to Mexico City at age 18 to live in a student boarding house and study law as one of a handful of female students. Her family, of comfortable means through their work in silver (or “pequebu,” petite bourgeoisie, according to La Nacha), were reluctant to let her leave. But Nacha’s vision to open up a law practice in the service of her community compelled her mother to support the move to Mexico City. In Nacha’s own words, she didn’t believe she had any sort of political vision but upon her arrival to the city, was introduced to new forms of thinking. She cut her long braids, visited her family less, began to participate in political study circles and became a member of the strike assembly at the School of Law.

The confrontation with the Mexican state in the summer of 1968 emerged during a seemingly innocuous dispute between student groups at two preparatory schools (the equivalent to secondary schools in the United States) on July 22. Riot police beat students to discourage dissent and maintain “public order.” Subsequent confrontations between students and granaderos (riot police) continued throughout the summer, culminating with a bazooka being fired at the Preparatory Number 3 in the center of Mexico City.

In response, students organized a march of silence on July 26 that commemorated the Cuban Revolution and unnerved the authoritarian Mexican state. By August 5, students formed the National Strike Committee (CNH), which included representatives from the UNAM, the National Polytechnical Institute, Chapingo Autonomous University, the Colegio de México, affiliated high schools, junior highs and autonomous learning projects like the Prepa Populares.

Student brigades, the backbone of the student mobilizations, communicated the details of the movement, and the indignation of hosting the 1968 Olympics when there were pressing national social and economic problems.

The “Pleigo Petitorio,” or strike demands, circulated across Mexico and international borders. The demands included:

- Freedom for all political prisoners

- The derogation of Article 145 of the Constitution which allowed for criminalization of political acts of protest

- Elimination of the riot police

- The firing of Luis Cueto and Raúl Mendiola, head of police in Mexico City

- Indemnization for the consequences of state repression

- The firing of functionaries responsible for the violence

By the time students formed the CNH and developed the strike petition, the Mexican government, under President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and Interior Secretary Luis Echeverría, had already planned military and police intervention to disrupt student organizing.

October 2, 1968

During the noon hours on October 2, members of the CNH met with Echeverría to begin the process of ending the strike, though the strike petition itself was not discussed. Later that afternoon, a previously planned rally was held at the Plaza of Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco, while a march to the Casco de San Tomás, affiliated with the National Polytechnical Institute, was cancelled due to the continued presence of the military in the school buildings.

Nacha vividly, and painfully, remembers the details of that fateful day and the saturation of the military in the city prior to the opening of the Olympic games.

She tells Latino Rebels, “Everyone remembers October 2 differently, which makes sense because we all remember it from the place we lived it.”

As the second rally speaker finished, a hovering helicopter dropped a red flare and then a green one. Shortly thereafter, sharpshooters who were part of the presidential security detail opened fire on the plaza and adjacent buildings, specifically the third floor patio of the Chihuahua building where CNH representatives were speaking and where Nacha and her peers were standing squarely in front of.

“In a matter of seconds, I saw a man with white gloves cover the mouth of the speaker and pull him back,” she recalls. “That’s when the rain of bullets started and I started to see bodies drop. In that moment we all started to run. I couldn’t believe what was happening.”

The advancing military units thought they were being attacked and returned fire. The families in attendance scattered, terrorized. They remember bullets, blood, cadavers, shoes, the sound of gunfire into the night, the sound of tanks and later buses and ambulances taking the wounded and dead to hospitals and military camps.

Today, 50 years later, a final accounting has yet to be given, even as researchers uncover new details of the planned operations, the role of the right-wing student groups secretly financed by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and the ways in which the federal intelligence authorities forced families to accept the government’s version of events to retrieve their loved ones bodies.

The following day, the Mexican government, with collusion from the prensa vendida (sell-out press) and the U.S., British and French embassies, blamed the students, communists infiltrators and foreigners, justifying the armed response by the military as a necessity to maintain law and order. While Nacha was able to escape, many others were not. In shock and fear, she left the city and returned to her home state where she spent the next three months.

On January 2, 1969, La Nacha decided to return to her apartment in Mexico City. Waiting for her were members of the Dirección Federal de Seguridad, a Mexican intelligence agency. Hooded and kidnapped, she was taken to a safe house and interrogated. Only four months after her initial detention, Ana Ignacia was again interrogated, transported to the Lecumberri and this time sentenced to 16 years in prison. La Nacha, along with three other women, Amada Velasco, Adela Salazar de Castillejo and Roberta “La Tita” Avendaño, were sentenced to three years at Santa Marta Acatitla prison for women, and were released under custody (which meant returning to the prison to sign in monthly).

As Nacha states, “a mi lo que me politizó fueron los golpes” (my political training came in the form of blows).

Through tears, she states, “I never imagined that they could do what they did to us students for marching in the streets, for demanding a more democratic state.”

50 Years of Impunity

1968 is a year that marks global rebellion: Prague, Paris, Vietnam, Mexico City. Yet in Mexico, the memory is of the massacre, the tragedy. Instead, we should also remember the movements that forced the violent hand of the Mexican state: students, unions, doctors, parents, and others who were brilliant in their imaginary, their strategies and tactics, and in their push to rupture authoritarian and patriarchal esquemas of the Mexican state and Mexican family.

However, the narrative of 1968 in Mexico has been largely written by men, and the same is true of the story of political prisoners. In the last two decades, the memoirs of Roberta “La Tita” Avendaño Testimonios de la cárcel, la libertar y el encierro, published in 1998, and Guadalupe Gladys Hernandez’ Ovarimonio: ¿Yo guerrillera?, published in 2013, have provided firsthand accounts and analysis of particular experiences of women in political movements.

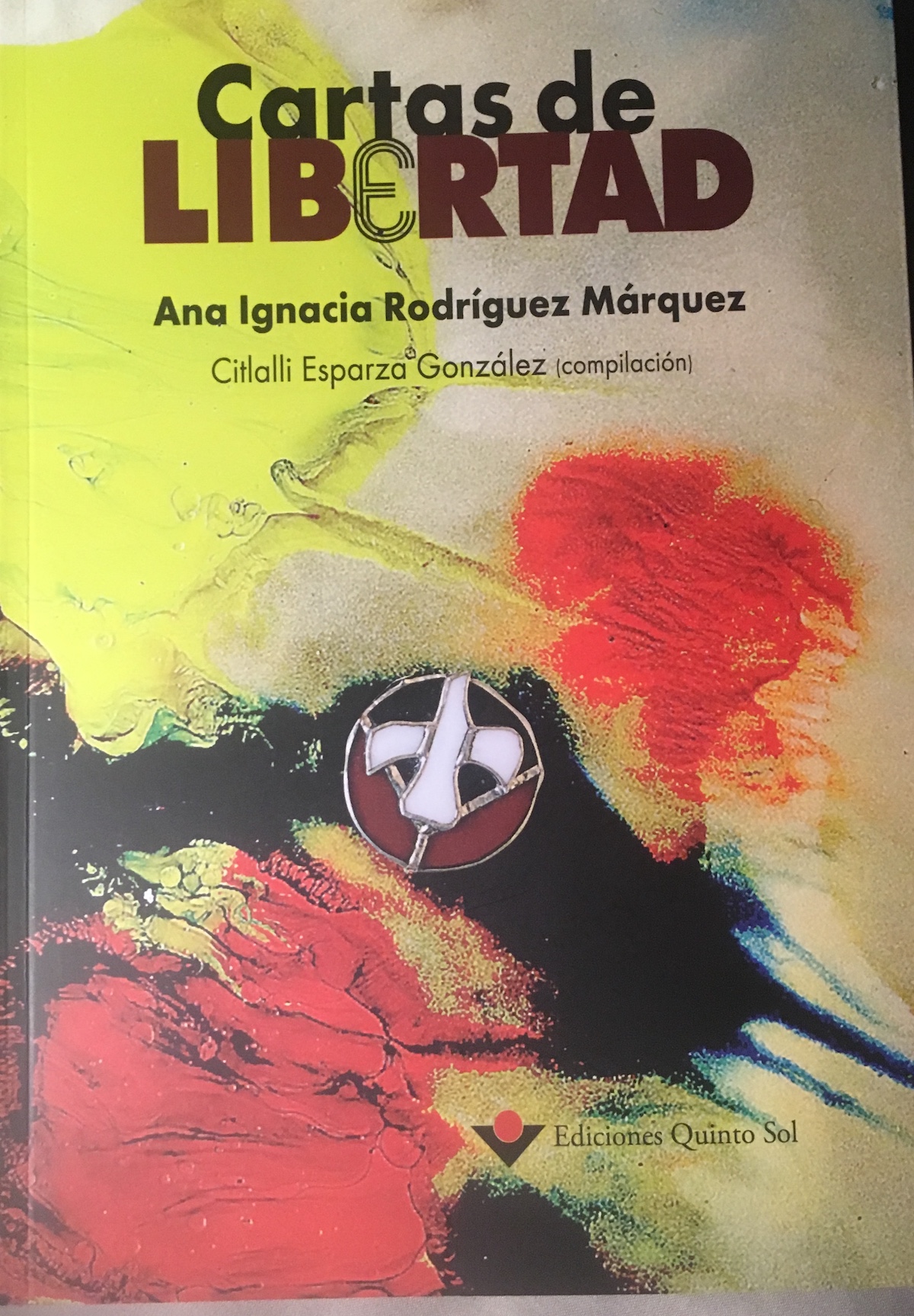

This year, La Nacha has also published an extraordinary book of letters, pictures, albums and other recuerdos from her three-years in prison. Cartas de libertad gives insight into the everyday life of surviving prison, emphasizing the importance of conviviality and shared experiences. Her memoir highlights the carework and exchange of intimacies and fears that come from sharing quarters.

While state violence conditioned the creation of La Nacha, Ana Ignacia continued to struggle during the 1970s, raising her two daughters, Aleida Habana and Tania Mercedes, as she worked for community relations in Mexico City’s Coyoacán neighborhood. In 1977, she joined the Comité del 68, invited by the late Raúl Garín Álvarez, respected student leader, writer and public figure of the student movement, and has dedicated her life to seeking justice for the massacre of Tlatelolco, while continuing to support political movements.,

In addition to organizing a commemorative marches, events, film festivals and acts of solidarity with political movements, the Comité del 68 has worked to bring Echeverría to justice for Tlatelolco and the violence of El Halconazo on June 10, 1971, where paid government infiltrators violently repressed a march in support of striking students in Monterrey, as well as the hundreds of deaths during Mexico’s Dirty War of the 70s and 80s.

In 2002, a special prosecutor to investigate political and social movements of the past brought genocide charges against Echeverría. Though the events of October 2, 1968 were determined by a federal court to constitute genocide, the evidence necessary to bring Echeverría to court was of a threshold impossible to reach: demonstrating the chain of command and proving a conspiracy through paper evidence.

On September 18, 2018, 50 years after the military violated the autonomy of the UNAM, the Comité del 68 processed a legal demand with the attorney general to reopen the case of genocide against Echeverría, not because they thought he would be sent to prison, but for the Mexican government to recognize that it had committed an act of genocide and terror against its own people. On September 25, 2018, a Mexican government body categorized the 1968 massacre as a “state crime.”

Yet this impunity continues with the names that echo state murder: Acteal, Aguas Blancas, Atenco, APPO, and Ayotzinapa. President-elect Andrés López Obrador has promised to reopen the investigations into the events of 1968. In what manner and with what juridical force, remains to be seen.

For the Comité del 68 and Ana Ignacia “La Nacha” Rodríguez, the last 10 months have been a whirlwind of presentations, interviews, roundtables and other events in commemoration of the 1968 movements. On October 2, 2018, at an event organized by the newly elected left-wing Mexico City government to memorialize those murdered at Tlateloloco, López Obrador invited the Comité del 68.

On arrival, in the middle of the plaza, circling the estela where there is a large 15-foot memorial to those murdered, was a four-foot metal barrier between the memorial and the public. La Nacha led the Comité del 68 in demanding that the barrier be removed, and spoke up about the importance of the newly elected city and federal officials not repeating the actions of previous authoritarian governments. López Obrador then publicly promised to never order the military to respond to social and political conflicts.

The October 2, 1968 commemorative event at Plaza de Tlaltelolco earlier this week. Photo by author.

Of the four women incarcerated as political prisoners, La Nacha is the last survivor. “Yo tengo que hablar por ellas, las que ya no viven.”

I have to speak for them, for those who no longer live.

Interview with La Nacha, January 2018. Photo by author.

Research for this project was funded by LASA/Ford Special Projects Grant cycle 2018.

***

Alan Eladio Gómez works at Arizona State University. He lives in Phoenix.

Michelle Téllez teaches in the department of Mexican-American Studies at the University of Arizona and is a public voices fellow at the OpEd Project.